Michael Winterbottom: ‘This is a film we made for people in Gaza’

Eleven Days in May, co-directed by the British filmmaker and Mohammed Sawwaf in Gaza, focuses on the children who died in last year’s war.

London, United Kingdom – A boy who adored Sergio Ramos and all things Real Madrid. A girl who wanted to become a journalist. A seven-year-old who had a brain condition and loved to eat tomatoes with every meal. A toddler who never grew tired of playing hide and seek behind a door. A seven-month-old boy who had just learned how to crawl and was showered in kisses by his siblings.

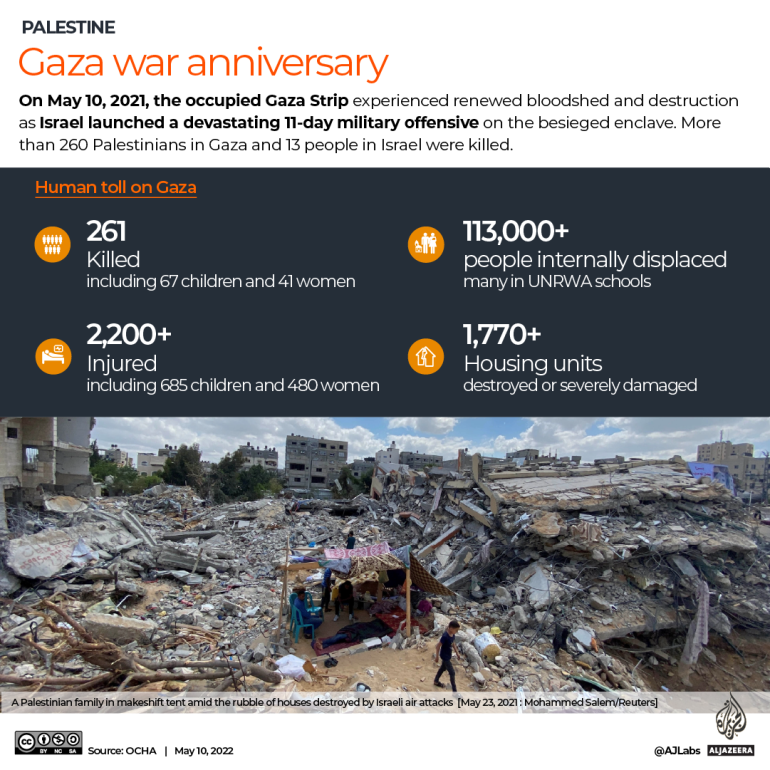

These are some of the 67 children who were killed in Israel’s 11-day bombing campaign on Gaza last May.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIn Gaza, young victims of Israeli bombing recount a brutal 2021

Families in Gaza still grieve a year after Israeli offensive

A year on from war, Gaza frustrated at slow reconstruction

Some suffered violent deaths in their sleep, others were killed while at home or in their neighbourhoods as they played or ran simple errands.

The conflict erupted as tensions over occupied East Jerusalem rose. Israel claimed it was intending to damage Hamas’s military abilities, but rights groups and several governments were alarmed by the growing number of child casualties – the overwhelming majority of whom were Palestinian.

After watching news of the attacks from Britain, Michael Winterbottom, a celebrated director, decided to make a film remembering these young victims – and so he linked up with Mohammed Sawwaf, a Palestinian filmmaker on the ground.

Sawwaf sent about 100 hours of footage to Winterbottom, who edited the documentary, narrated by Kate Winslet, in a dark cutting room in London.

For about 80 minutes, the audience witnesses mere moments of lifetime pains.

Siblings, some so young that they will soon lose vivid memories of their killed brothers or sisters, shuffle nervously as they speak about their bereavement. Mothers and fathers put on brave faces in front of their surviving children, but break into tears when filmed alone. Keepsakes are carefully laid out in front of the camera – a Star Wars hoodie, a school certificate, the kind of necklace that costs a pittance but means the world to a little girl.

And we see mobile phone photos and videos, complete with cartoon-like Snapchat filters, showing the children full of life and happy before images of them which attest to the grimmest realities of war – small bodies, bloodied, and torn into pieces.

Al Jazeera spoke to Winterbottom and Sawwaf about their film, Eleven Days in May:

Al Jazeera: Few directors in Western nations have tackled events in Gaza, where there have been many tragedies. Why do you think that is?

Michael Winterbottom: I don’t know. From my point of view, having seen it on the news like most people, it just felt like what was happening was shocking – obviously. But also [shocking] that it happened before – you see things on news and then you forget about them. Maybe that forgetting about things is why they keep happening again. Perhaps if you remember events like that, and what they feel like at the time, perhaps they are less likely to happen again.

Mohammed Sawwaf: Maybe one of the reasons is Israel’s refusal to accept any criticism – it is quick in reacting to any criticism and fights anyone making such criticism, whether directly or through its lobby groups in Europe.

Some of those filmmakers and influencers may have been affected by the Israeli narrative, its distortion of the Palestinian image and its founding of a negative stereotype against them, especially in Gaza.

Al Jazeera: What propelled you to this particular subject – the loss of children?

Winterbottom: As a parent, the worst thing you can imagine is losing a child. For people in Gaza, it’s happened before and it’s happening again. That feeling as a parent – can you protect your children, can you look after them? That seemed like it would be something good to focus on.

[In the film, you see the stories of] child after child, you get to know them a little bit – the accumulation of it is what’s powerful.

We hope that makes people realise bombing is not a solution to the problem. It would be great to think that the more people feel that, the less likely it is to continue.

Al Jazeera: In the comments section under an early review of your film, you have already been decried as an anti-Semite. How do you feel about this label?

Winterbottom: I don’t look at anything like that. It’s obviously wrong. Our film is what’s showing what’s happening to people in Gaza. The idea that that is anti-Semitic is ridiculous.

Al Jazeera: You are releasing a film about a Middle Eastern war when there is a huge conflict in Europe. How can we compare – or should we even compare – the response to the victims of both tragedies?

Winterbottom: The experience of a family losing a child is the same, whether it’s in Ukraine or it’s in Gaza. I think our response has been different. The response to the war in Ukraine has been very much – we must do something to stop it, what’s being done is terrible, that the people who are doing it are wrong, that we should be doing everything that we can to help the people who are being bombed.

I don’t think that has really been our response to what’s happening in Gaza, or for that matter what’s happening in Yemen and after all, in this century, we’ve done a fair share of bombing ourselves.

It would be good to think people’s reactions and feelings about what’s happening in Ukraine would perhaps make them also think we should feel like that about other conflicts throughout the world, whether in Gaza or elsewhere.

Sawwaf: Unfortunately, we must wait for a war to happen in Europe until the West notices and feels the horridness of war and its victims.

I sometimes find it troubling to compare what is happening in Palestine and Ukraine, despite an outpouring of sympathy from Palestinians to the Ukrainian people. It is very easy for those who have felt pain to feel the pain of others.

The people of Gaza and Palestinians in general have been suffering the pains of war and loss for many years. But the difference is that Ukraine found someone to stand by it, support it, empathise with it, accept its refugees and provide them with safety.

It has found countries that have imposed sanctions on the oppressor, Russia, whereas unfortunately Gaza has been under siege for 16 years and there is no safe place to escape to.

With Israel, everyone closes their ears and eyes to the victims.

Israel is never punished or deterred by the international community, and so continues to launch war after war on this poor and besieged strip. This leads to people losing hope. Many here believe the world views them as an inferior race and that their blood is cheaper than that of others.

Al Jazeera: What’s behind those different responses?

Winterbottom: When you get to know people, you care more for them. It’s a natural human instinct, you want them to be safe. You don’t want them to be attacked.

If you don’t know them and perhaps you know the attackers better, then you see if from a different perspective.

Almost all the reporting of Ukraine has been from the perspective of people being bombed, and the media has done a good job of showing those people – just as they did a good job in Syria.

Perhaps in Gaza, we don’t see as much of the families, of the children, of normal life in Gaza. Because people don’t feel we know them so well, we don’t care so much.

That’s the idea of the film – in a small way, we get to know the children, the families. You get to know more strongly the tragedy of them being killed.

I hope the film is moving – [watching it you become] very aware of the families’ losses and their grief.

Al Jazeera: How did you convince the characters to speak about such a traumatic event, and how did you put them at ease?

Sawwaf: We asked them to reopen their wounds, but also convinced them of the importance of people hearing their voices and seeing their children. We told them that their children must not be mere numbers counted in news bulletins and that everyone should know that their children dreamt of happy futures, the same as all the children of the world.

We were able to form a friendship with the families. We sat with them and visited them several times and built trust. This helped us convince them of the need to talk in front of the camera.

When they fetched their children’s belongings and toys, their books and pencils – this was more tragic and painful for the families than narrating the incidents themselves. And for us, the team, listening to them was more difficult for us than the war itself.

Al Jazeera: In your film, you show images of dead children right after attacks and as their bodies are carried to graveyards in funeral processions. How did you decide on whether to show these harrowing scenes?

Winterbottom: A lot of the archive – photographs of the children when they were happy and alive, and of them then they were dead – they were all given by the families to Mohammed, things they wanted to be included in the film. It wasn’t like we were asking them – trying to persuade them.

That remembering of people is different in different cultures – perhaps that wouldn’t happen in England.

It felt to me that it was important to see them … In a way, it is partly down to why you’re showing them. We’re trying to show how terrible and awful it must be.

Al Jazeera: At least 261 people were killed in the conflict, according to Gaza’s health ministry. On the Israeli side, 13 were killed, including two Thai workers, a Palestinian citizen of Israel and his daughter. One criticism of the film that might emerge is your choice not to feature any Israeli victims. How would you respond to that?

Winterbottom: From my point of view, this is a film we made for people in Gaza. I think that’s legitimate. I don’t think you have to make a film about everything at the same time. It’s about talking to families in Gaza who have lost their children in the bombing campaign.

Al Jazeera: Why do you think there are fewer calls from politicians globally to try Israeli leaders for war crimes, compared with those in Russia or Syria?

Sawwaf: The violations and crimes carried out by Israel against the Palestinians are clear and are documented by human rights organisations and UN reports that condemn Israel. However, the positions of the world’s governments are, if not complicit, then shy and soft.

Many families we spoke to said that the world has been watching their tragedy for 74 years, and has done nothing.

Editor’s note: These interviews were lightly edited for brevity.