Election runoff an image of a polarised France, analysts say

Rivals Macron and Le Pen are set to battle for the presidency in what is projected to be a tight second round on April 24.

Paris, France – It was an outcome predicted by many, and a repeat of the same vote five years ago.

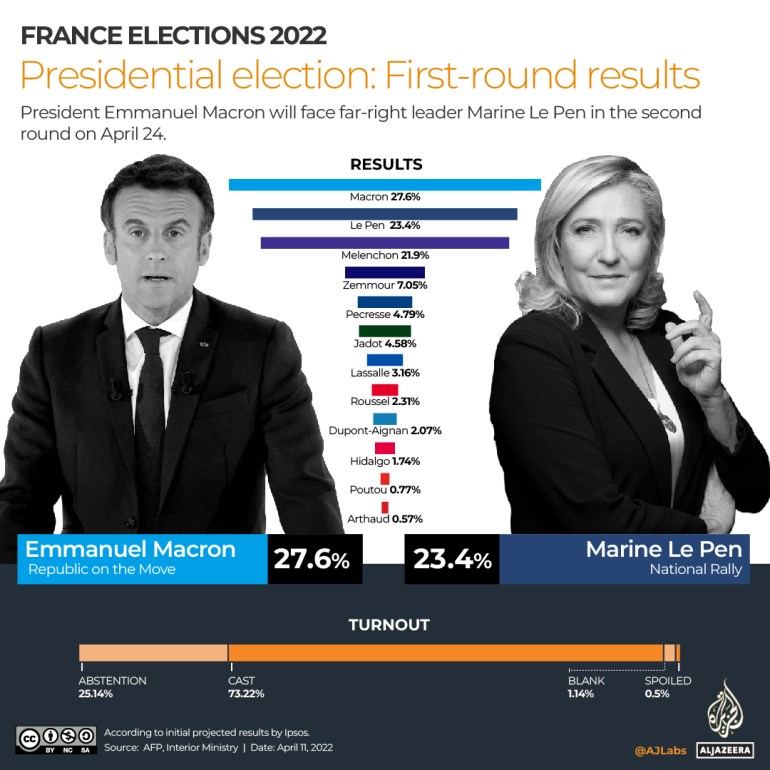

Incumbent President Emmanuel Macron and far-right leader Marine Le Pen on Sunday came out on top in the first round of the French presidential election, securing their places in the runoff that will be held in two weeks.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsUkraine war serves as backdrop to France’s presidential elections

French election: Minority youth voice frustrations ahead of vote

This time, Macron gained 27.6 percent of the vote, compared with 24 percent in the 2017 first round, and Le Pen slightly improved on her previous gain to claim 23.4 percent of the vote.

Far-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon just missed the cut-off for the second round, gathering 21.9 percent.

Polls are forecasting a tight second round on April 24, with Macron winning 51 percent of the vote and Le Pen 49 percent. However, with the gap so close, a projected victory either way will be within the margin of error.

Two visions

Virginie Martin, a research professor at Kedge Business School, said the runoff is a consequence of an increasingly polarised France, with each of the top two candidates presenting two different images of society.

“Macron destroyed the left-right divide,” she said, in reference to the president upending France’s established political system with his 2017 election win. “As a result, the oppositions are moving to the far right and far left. This is a problem.”

Le Pen has capitalised on this, and in her speech on Sunday night at the Pavillon Chesnaie du Roy, she stated her voters had a choice for opposite visions of France: “One of division, injustice and disorder imposed by Emmanuel Macron for the benefit of a few, [and] the other a rallying together of French people around social justice and protection”.

These two images are irreconcilable, Martin said. On one hand, Macron – nicknamed the president of the rich – embodies the France of educated, wealthy people who support globalisation, NATO and are pro-Europe. On the other, Le Pen represents the blue-collar working class who have reservations about Europe and NATO.

For James Shield, a professor of French studies at the University of Warwick, the rematch between the pro-Europe economic liberal and the populist-nationalist is an indictment of a French political establishment that has failed to renew itself in the five years since Macron came to power.

“Having promised on his election in 2017 to ‘remove the reasons for voting for the extremes’, Macron finds himself confronting now a devastated political landscape where only the extremes [of both right and left] present an alternative to his centrist administration, with far-right candidates the weightiest grouping in this election,” he told Al Jazeera.

The result is also a condemnation of the crushing defeat suffered by the two once hegemonic parties in France, the centre-left Socialist Party and the centre-right Les Republicains, which have entered “an existential crisis from which neither may recover”, he added.

Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris and Socialist Party candidate, finished 10th, out of 12 candidates, with just 1.7 percent of the vote – an unprecedented result for the party.

“It’s a catastrophe,” said Jean-Yves Dormagen, a professor in political science at Montpellier University. “It’s the final act for the Socialist Party – it no longer has space in politics.”

It is just as bad for Les Republicains. The party’s candidate, Valerie Pecresse, came in fifth place, scoring lower than far-right leader Eric Zemmour with just 4.8 percent of the vote.

“It’s an issue of candidate casting, or image, or public presence,” Dormagen said. “These parties don’t match anyone’s expectations now.”

Disenchantment with Macron

Macron and Le Pen resumed campaigning on Monday, with the former heading to the northern Hauts-de-France region. Macron was largely absent from most of the campaign trail prior to Sunday, spending most of his time focusing on diplomatic efforts over the war in Ukraine.

Come April 24, it will eventually boil down to who Mélenchon’s electorate will cast their votes for. The left-wing leader told his supporters not a single vote should go to the far right, but stopped short of endorsing Macron. Meanwhile, Le Pen, who cultivated her appeal to the working class by conducting her campaign to focus primarily on economic issues, will count on siphoning some of Mélenchon’s support base, who are disenchanted with the right-wing policies that characterised Macron’s first term.

“The majority of Mélenchon’s base – union workers, intellectuals, immigrants – don’t want to vote for Macron, which should worry him,” Dormagen said. “They reject Macron and his policies. But how will they react when they see polls projecting a victory for Le Pen? That might change their views on the matter.”

A Le Pen win would send political shockwaves within Europe, pivoting France to join the list of other countries ruled by right-wing populism. The “Republican front” against Le Pen, which worked well in 2017 after people rallied for Macron to prevent the far-right leader from winning, looks less sturdy now, especially with far-right candidates, including Zemmour and sovereign nationalist Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, securing as a whole a third of the vote. Furthermore, the far-right political spectrum has widened over the past five years, with Le Pen presenting herself as a less divisive figure.

“We know that Mélenchon’s voters don’t want to choose between Macron and Le Pen,” Martin said. “But some of them will vote for her. Le Pen will collect a lot of rebel votes.”

Macron, who started out as the clear favourite but is now fighting as a beleaguered incumbent, has his work cut out for him, Shield said.

There was a palpable sense of relief at the Paris Expo Porte de Versailles convention centre, where members of Macron’s party had gathered when the results came in on Sunday night. Supporters began singing the national anthem, La Marseillaise and chanted: “And one, and two and five years more!”

“Insisting on the dangers of electing Marine Le Pen will not be enough,” Shield said. “Macron will have to both defend his record over the past five years and set out a clear vision of where he wishes to take France in the next five. So far he has not done this convincingly.”

Another factor is the loathing that Macron inspires in a large sector of the French voting public, Shield added.

“This time there will be an ‘anyone but Macron’ vote just as there will be, again for some, an ‘anyone but Le Pen’ vote,” he said. “The second round will depend on who’s loved more, but also who’s hated more.”