As war ravages Ukraine, refugee crisis hits Polish cities

While there is no shortage of generosity in Ukraine’s Central European neighbour, space runs out in several cities.

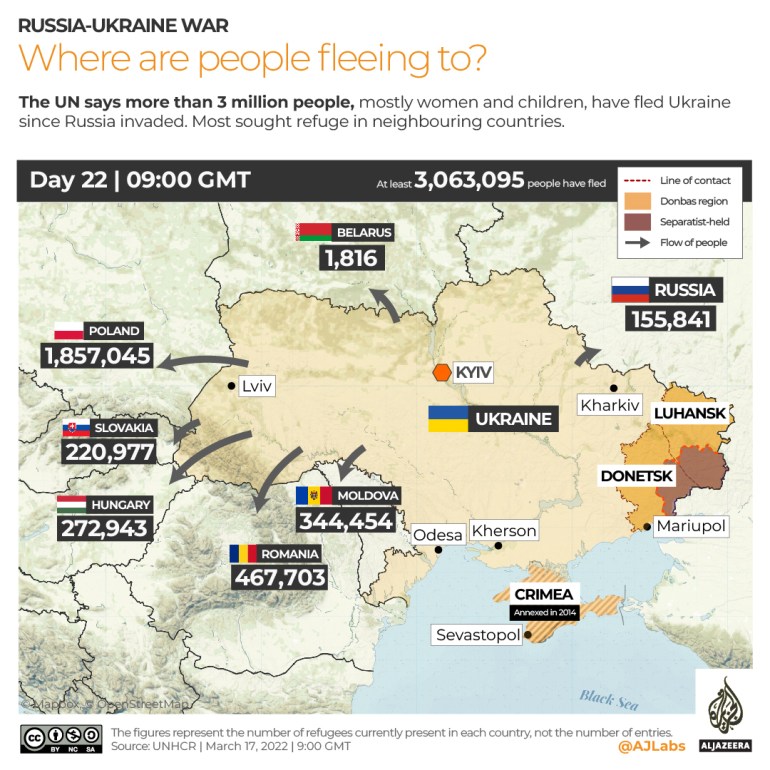

Krakow, Poland – In four weeks of war, three million people have left war-ravaged Ukraine with the majority crossing into Poland.

While the welcome from the government and civil society has been open-armed, space is running out for the newcomers.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIs a nuclear disaster likely in Ukraine?

Will the ICC investigation help or hinder peace in Ukraine?

Broken dreams: Palestinian students who escaped the Ukraine war

Krzysztof Chawrona, a 41-year-old entrepreneur from Krakow and founder of Nidaros, an organisation that supports Ukrainian nationals, is among those who have given up space in their own homes for refugees.

“My son is staying with his auntie because I gave my flat away to eight refugees,” Chawrona, father of four, told Al Jazeera. “In my second flat, which I used to rent out to one company, there are seven people in 40 square metres. And they are grateful that they have a place to stay.”

He said that on February 24, the first day of Russia’s invasion, cities across Poland became quickly stretched. In Krakow, people from Ukraine slept on the pavement in front of his foundation’s office.

And as each day passes, thousands more people arrive by train, seeking shelter in the main cities of Warsaw, Krakow and Wroclaw.

Chawrona opened his foundation four years ago to help Ukrainian migrant workers settle in and adapt to new realities while learning the language and getting paperwork done.

Many ended up being employed in his construction company.

But the organisation’s focus has now switched to supporting refugees.

When the war began, Chawrona’s first step was to evacuate the families of his Ukrainian employees to Poland.

The Nidaros office has also been converted into a 60-bed refugee shelter.

So far, the group has supported 1,200 people in finding accommodation in Krakow.

On weekends, Chawrona travels alone into Ukraine, taking medicine and other essential items for hospitals in Vinnytsia and Khmelnytskyi. A friend used to go with him but no longer takes the risk after coming under shelling.

However, the biggest challenge for his group is financing.

“We had 70,000 zloty [$16,600] in our budget,” he said. “We’re now out of cash.

“We only have two microwaves. We have dozens of beds and we have to change the sheets every day, but we only have one small washing machine. We cannot cope with all this financially. The city is doing a lot, but it’s nothing when we look at the actual needs.”

About 150,000 Ukrainians have so far travelled to Krakow.

Local authorities have turned every available space – sports halls, dormitories and hotels – into shelters, and it is currently near impossible to find a flat or an affordable hotel room in the city of 700,000.

The city council’s crisis response fund was 19 million zloty ($4.5m); it has already spent more than 16 million ($3.8m).

These days, Malgorzata Jantos, deputy of the Krakow City Council and a lecturer in philosophy, spends all her time trying to help refugees find a home.

While she sips morning coffee in her kitchen, her phone does not stop ringing.

“Krakow is stuck. All halls, dormitories are packed. So we have to find places out of the city. The situation is hard because Ukrainians don’t want to leave,” Jantos told Al Jazeera, explaining that Ukrainians prefer to stick to big cities, fearing that smaller towns and villages lack infrastructure and job opportunities.

Looking ahead, it will likely be difficult to convince people to go abroad.

Poland is close to Ukraine, where many hope to return, and a familiar place culturally.

“Last night, a train to Hanover [in Germany] had 400 places and only 100 people left. People are afraid of leaving. Here they can communicate and find a job. In other countries it’s more difficult. An older Ukrainian man approached me and cried that he does not imagine life in Germany. He only wants to survive five more years and die,” Jantos said.

Krakow has, in effect, turned into a large humanitarian organisation as locals mobilised en masse to support Ukrainians.

But many are calling for European Union assistance and demanding more from the government in Warsaw to deal with the crisis.

“The central government must have been informed by the US about the war coming, and yet they didn’t prepare for the crisis,” said Jantos.

According to experts, Poland should be preparing for months, if not years, of crisis.

“I think that per analogy with the Syrian conflict – although there are many differences – even [25 percent] of Ukrainian citizens might leave the country.

“It is about 10 million people and even half of them might want to stay close to home, including Poland,” said Konrad Pędziwiatr, professor at the department of international affairs at the Krakow University of Economics.

“Big cities have already exploited their absorption capacities … But we also know from other migrant crises, in other parts of the world, that cities have the capacity of enlarging themselves, even more than their governments would expect.

“What we need is to start thinking more creatively, which will allow us to accept even more refugees.”

But the higher the number of refugees, the lower the quality of reception, he said.

One solution might be found in relocating refugees within Poland.

Smaller towns and villages have not yet exploited their capacity when it comes to healthcare and childcare – important provisions given the high number of children arriving.

For that, observers said Poland needs a clear information campaign that highlights to refugees the benefits of settling in smaller towns. Otherwise, Polish cities will struggle to function.

“Many people sleep at train stations. I’m trying to find accommodation for them, we are all networked and the network is a blessing,” Jantos said. “But there are so many people that accommodating everyone will soon become impossible.”