Fears for Māori as New Zealand opens up amid Omicron wave

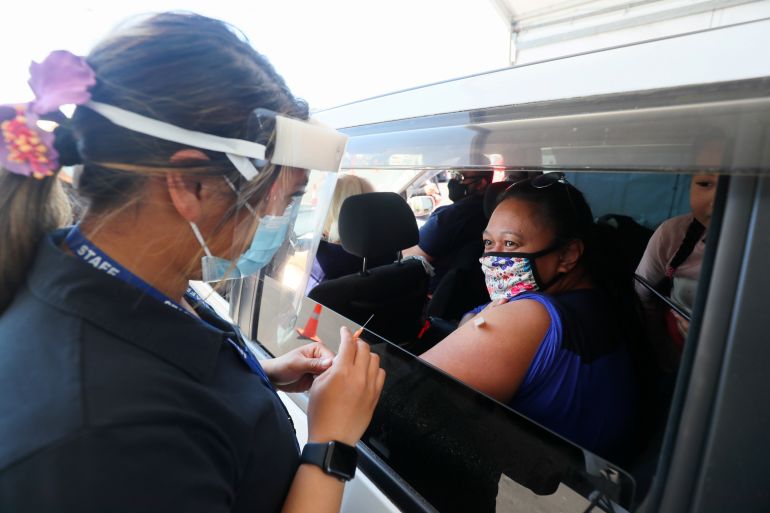

Experts say vaccine rollout failed to involve the Indigenous community or recognise their greater health risks.

Wellington, New Zealand – New Zealand is one of the most vaccinated countries in the world, with some 93 percent of people over the age of 12 fully vaccinated, according to the latest figures.

But as the country prepares for a wave of Omicron, Māori experts say New Zealand’s response has left the Māori population uniquely vulnerable.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAs Omicron pushes the West to reopen, Asia hunkers down

New Zealand PM Ardern postpones wedding amid Omicron curbs

No way home: Overseas New Zealanders despair at tightened borders

And they say racist policies are to blame.

“We’re seeing racial rhetoric coming to the fore,” said former Māori Council chief executive Matt Tukaki.

“I’ve never seen so much racism in the past two years. The irony is what we are all attempting to do here is to prevent people dying prematurely from a preventable disease.

“It’s disheartening that Māori weren’t considered a priority from the get-go.”

Before Omicron, there was Delta

Even before Omicron arrived, a report in December from the Waitangi Tribunal – a commission that deals with public claims brought by Māori – warned that the government’s vaccination plan put Māori at “disproportionate risk of Delta infection” compared with other ethnic groups in New Zealand.

It added that decisions had been made without adequate consultation, and despite strong opposition from Māori community leaders.

During the consultation process, Māori representatives found the authorities failed to jointly design and engage with Māori on the plan, finding the approach at times disrespectful. The lack of adequate protection for Māori afforded by the government’s vaccination policy resulted in prejudice, the report read.

Data until December 13 showed Māori made up half the country’s infections with the Delta strain, 38.6 percent of hospital admissions for the variant, and 45 percent of associated deaths, according to the tribunal report.

Māori make up only 15.6 percent of the population, it noted.

Although the findings are not binding, the Tribunal recommended the authorities improve the collection of data on ethnicity, provide better support for Māori providers and communities, and a more equitable rollout for booster shots and paediatric vaccines.

Health Minister Chris Hipkins told Al Jazeera the country was in a “really good place” with the vaccine rollout.

“This is the largest vaccination campaign in New Zealand’s history … with over 3.9 million people fully vaccinated [as of 25 January],” he said.

“For Māori, vaccination rates have seen a big jump in the last few months with 89 percent of eligible Māori partially vaccinated and 84 percent fully vaccinated.”

‘Structurally racist’

Like many countries, New Zealand built its vaccination rollout around age and health status.

Front-line and border workers were first to get the shots in February 2020, followed by South Aucklanders over 65 with underlying health issues at the end of March, after an outbreak linked to a church in the area.

People over 50 followed in June, and from September 1 last year, anyone aged 12 and over was eligible to be vaccinated.

But Māori researcher Rawiri Taonui says the focus on age failed to consider the 150,000 Māori who are older than 45 but have the same risk profile as an average 70-year-old white person.

“The vaccine rollout was structurally racist, even if that was not the intention,” he told Al Jazeera.

A COVID-19 Māori Vaccine and Immunisation Plan was published in March 2021 with more than 120 million New Zealand dollars ($79.8m) set aside for funding. The Ministry of Health disbursed a total of 35.5 million New Zealand dollars ($23.6m) between March 2020 and December 2021 to support Māori health and social service organisations.

According to the Waitangi Tribunal report, the plan showed the authorities understood that an age-based priority would disadvantage Māori because of the shorter life expectancy despite the younger population.

While it received advice from the Ministry of Health, as well as from officials and experts, that the strategy should include an age adjustment for Māori, the Cabinet declined to include the adjustment, the report found.

“Cabinet’s decision to reject advice from its own officials to adopt an age adjustment for Māori in the age-based vaccine rollout breached the Treaty principles of active protection and equity,” it said.

The problem was compounded when authorities failed to share key data on Māori vaccinations with the Māori health agency and the community leaders who were ready to drive home the vaccination message and deliver the vaccines.

“We are not running around in grass skirts and chucking spears at each other,” said Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency chief executive John Tamihere. “We know how to meet the needs of our people. We need to be given the opportunity and resourcing,” he said.

In an affidavit to the Tribunal, Hipkins said that at the time the country was confronted with limited vaccine supply and that the best way to protect all New Zealanders, including the most vulnerable, was to attempt to keep the virus out of the country.

“[D]iversity of the limited available vaccine supply towards younger Maori would have entailed diverting it away from other more vulnerable groups,” he said.

Families left behind

Māori Party Member of Parliament Debbie Ngarewa-Packer says the result is that vulnerable families have been left behind.

“[I hope] we don’t see a repeat of past mistakes with whānau [families] wanting to access vaccination for their tamariki [children]”, she told Al Jazeera.

“The public health director told the government it needed to prioritise Māori but it cherry-picked the advice so that it was a mono-culture response.”

The Ministry of Health’s National Immunisation Programme Director Astrid Koornneef says the sequencing framework upheld and honoured Te Tiriti o Waitangi (New Zealand’s founding document) and was developed to ensure the most at-risk people were vaccinated at the right time.

With New Zealand now lifting internal movement controls, and the arrival of the Omicron variant, Taonui worries Māori face disproportionate risk.

As of January 25, about 4 percent – roughly 168,360 people – of the New Zealand population remained unvaccinated.

But in some Māori communities, the rate is far higher.

Taonui worries that the relaxation at a time when a more transmissible variant is on the rise will lead to Māori accounting for 50 percent of index figures – whether active cases, hospital admissions or deaths – by the end of this month.

As of February 7, New Zealand has reported 17,876 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 53 deaths, which compares well with countries of a similar size. Denmark, for example, has had nearly 1.9 million cases and 3,863 deaths.

Tamihere took the Ministry of Health to court to overturn the government’s decision not to share vaccination data.

In November, he won the judicial review.

“If we have access to strategic data we can send texts directly to people, door-knock, and drive down the street with music pumping,” he said. “Whether it’s giving food vouchers or takeaways we need to make the vaccination process accessible and appealing. It doesn’t matter what works but rather that our people have been given the opportunity.”

The Ministry of Health’s Koornneef says the ministry respects the High Court decision, and that it had agreed to share health data about individual Māori living in Northland, Hawke’s Bay, Whanganui, Wairarapa, Bay of Plenty, and the Lakes regions who had not had a first dose of the vaccine.

It said it would consider providing further data to support the rollout of booster shots and the vaccination of children next year if the agency were to “request the information at the appropriate time, and the request will be considered by the Ministry at that time, informed by the Court decisions and existing approvals for disclosure of information.”

In the year ending June 2020, about one in five Māori children lived in poverty – meaning they lived in houses that were living on a disposable income of less than 50 percent of the national average. Māori children made up nearly half of the number of children in material hardship, according to Statistics New Zealand data.

Many Māori also live in close quarters and in the kind of conditions in which respiratory illnesses like the coronavirus are able to thrive.

Tukaki has been working with those in need and says he speaks to as many as 40 people a day who are “struggling”. The requirement for isolation if they test positive is only likely to make things worse.

He recalls delivering food to a mother of two children who tested positive for COVID-19 in December.

She could not go to work and was living on the edge of financial ruin in a substandard house.

“This is the reality we are facing right now,” he said.