Chinese exiles: Boycott Winter Olympics over Uighur ‘genocide’

Dissidents join rights groups in warning against any effort by Beijing to use Games as ‘sports-washing opportunity’.

After he was arrested at the age of 20 in China’s Xinjiang and eventually escaped to Turkey in 2005, all Kuzzat Altay wanted was to live in peace in the United States, where he finally ended up in 2008.

But the Uighur refugee’s longing for a different life in his adopted homeland was disrupted in 2018 when he learned that his father had been taken by Chinese authorities from their home in Urumqi, Xinjiang’s capital.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsBiden signs law banning goods made in China’s Xinjiang region

UN human rights chief allowed to visit Xinjiang after Olympics

“He disappeared for two years. I thought he was murdered in the camp,” Altay told Al Jazeera after his father was detained in one of a network of camps where the United Nations says at least a million Muslim Uighurs are believed to have been held against their will by authorities since mid-2017.

Since then, Altay has become one of the diaspora’s most recognisable Uighur human rights activists and leaders, speaking out on China’s alleged repression of Xinjiang’s Turkic-speaking Muslim minority as president of the Uyghur American Association in Washington, DC.

Human Rights Watch calls China’s treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang a crime against humanity, while the US Department of State says “genocide” has been committed. China says the camps are skills training centres and necessary to counter “extremism”.

It was unclear when Altay’s father was released exactly, but the next time he saw him was in 2020, when he appeared on TV denouncing his son.

Different world, but the same fate

It was also in 2018 that political cartoonist and artist Badiucao found his life turned upside down after his family members were taken in for interrogation by China’s national security authorities because of his activism.

3/ The Beijing 2022 collection was initially released at the New World Center’s Soundscape Park as part of the 2021 Oslo Freedom Forum in Miami. HRF subsequently canvased the collection at various locations around Miami during Art Basel Miami Beach 2021. https://t.co/ufVCMWwfsD pic.twitter.com/HyrVvSMLr3

— Human Rights Foundation (@HRF) January 31, 2022

At the time of their detention, the Shanghai native, who had moved to Australia, was planning his first major art exhibition in Hong Kong – poking fun at Beijing’s censorship and growing authoritarian rule in the territory.

Badiucao, whose most prominent works include Carrie Lam, 2018, which combines the faces of the city’s chief executive and Chinese leader Xi Jinping, was forced to cancel, and since 2018 has cut off all contact with the members of his family who remain in China.

He finally managed to put on a show in the Italian city of Brescia in 2021. But not before the Chinese government had tried and failed to convince officials in Italy to stop the show at the last minute.

Altay and Badiucao come from two different worlds within China but have suffered similar fates. As Beijing prepares to host the Winter Games, which start on Friday, the two exiles have found common cause in calling for boycotts and sanctions against China to force the government to improve its human rights record.

The two have also joined international rights groups in warning the world against any effort by Beijing to use the 2022 Olympics to gloss over state-backed rights abuses.

Like the Summer Games in 2008, when China had promised to become “a more open and democratic society”, Badiucao told Al Jazeera, “it is obvious” that Beijing will try once again to “create an illusion to the world that all is good” in the country during this year’s Winter Games.

“But what we have witnessed is the incredible diminishing of those hopes and expectations from a human rights perspective,” he said, citing the “slave labour treatment” of Uighurs in Xinjiang, as well as the “draconian” lockdown measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 and the crackdown in Hong Kong.

In the run-up to Beijing 2022, Badiucao released a new series of artworks and videos that recreate images of winter sporting events and, on closer inspection, reveal abuses by China.

‘Sports-washing’ abuses

Amnesty International, which last year described the situation in Xinjiang as a “dystopian hellscape“, has also cautioned against the risk of “sports-washing” as a result of the Games.

Last week, the organisation’s China researcher Alkan Akad said the event “should not be used as a distraction from China’s appalling human rights record” and was an opportunity to highlight alleged abuses.

“The Beijing Winter Olympics must not be allowed to pass as a mere sports-washing opportunity for the Chinese authorities, and the international community must not become complicit in a propaganda exercise,” Akad said.

Beijing has repeatedly denied the allegations of genocide in Xinjiang, saying the camps were established to fight extremism and help Uighurs improve their skills.

On Friday, China reportedly agreed to allow UN human rights chief Michelle Bachelet to travel to Xinjiang, but only after the conclusion of the Olympics, and on the condition that the trip is “friendly” and not framed as an investigation. Bachelet has been calling for unfettered access to the area since 2018.

The Chinese government has also defended its COVID-19 policies, saying the approach helped curb mass infection and fatalities in the country of more than a billion people where the first cases of the virus were reported in Wuhan in late 2019.

It has also dismissed criticism of its actions in Hong Kong as an effort to interfere with the country’s internal affairs.

‘Torn apart’

For those who have encountered the long arm of the Chinese state, however, the ordeal has become increasingly personal.

Born in Urumqi, Harvard-educated lawyer Rayhan Asat saw her “beautiful and loving family torn apart”, after her younger brother, Ekpar, was detained and later sentenced to more than a decade in prison purportedly for “inciting ethnic hatred and ethnic discrimination”.

Ekpar had just returned to Xinjiang after attending a US State Department-sponsored course in 2016 when he was taken in by authorities. It is believed that at some point in 2019, he was placed in solitary confinement.

It was only in 2020 that Asat made her story public, after years of agonising private efforts to secure her brother’s release.

She has never returned to China for fear of being detained and has only limited contact with her parents.

“I feel their absence in my life every day. I can never get used to, or accept a life where I can’t cry in my parent’s loving arms or turn to my brother for advice on relationships, career, or life challenges,” she told Al Jazeera.

“The Chinese government took so much from me, including my loving relationship with my parents. When one person goes to prison, and the entire family goes with them.”

1. When it comes to mass atrocities, the perpetrators take comfort in knowing that the mass numbers of victims can dehumanize the victims as well as bystanders. People become data in their crimes against humanity. But the victims are someone’s brother, mother, and father. pic.twitter.com/kZgtuxe7MI

— Rayhan E. Asat (@RayhanAsat) January 4, 2022

Altay, the Uighur exile, says that since his activism in the US, the Chinese government has continued to inflict more pain on his family, forcing his father to appear on national television to ask him to stop criticising Beijing.

After Altay’s father was released from detention, he was still subjected to constant surveillance and humiliation, even when going out for groceries.

“The facial recognition cam will trigger an alarm, and he will be interrogated anywhere he goes,” Altay said.

“He went out of the camp with a broken leg, and the Chinese authorities did not allow him to go to the doctor for treatment. He is still in pain.”

Altay also learned that his father told his brother that if he is taken again by authorities, “he wants to die without pain and torture”.

‘Information black hole’

Altay is sceptical of the Chinese government’s reports on the situation in Xinjiang.

“The Uighur region is an information black hole,” he said. “Last year I saw the official Xinjiang newspaper claiming 4.7 million Uighurs have been ‘re-educated’,” he said.

He also said he heard of news reports that the government has moved people “from the concentration camps to prisons”, that China wants to label those detainees as “criminals”.

Altay says that while the world is starting to listen to stories about the plight of Uighurs, “it’s not enough to stop the genocide”.

In December, the Uighur community in the US successfully lobbied for the passage into law of legislation that bans goods made in the Xinjiang region. Altay is urging other countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand and EU countries to pass similar laws.

“That’s a tangible step to save Uighur lives,” he said.

“When China can’t sell their products any more, like the old days, when their economy suffers, they would have no choice but let Uighurs go.”

‘Speak up’

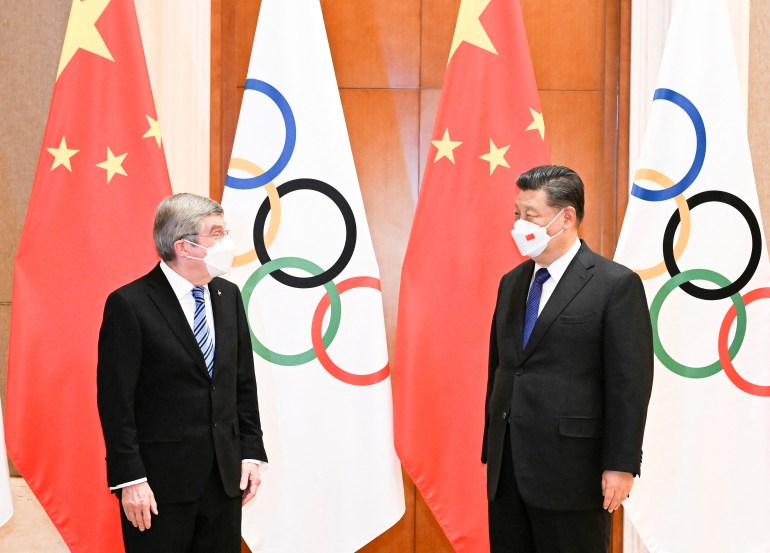

Aside from the diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Olympics initiated by the US and several other countries, athletes who are participating must also speak up, and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) must ensure their safety from punishment, said the artist Badiucao.

“The Olympics is all about celebrating humanity. It is all about upholding human rights. So it is important that athletes understand their responsibility and their power,” he said.

Spectators of the Games around the world should also call out the multinational companies sponsoring the event, he said.

“We should hold those companies responsible as well. That if they want to sell the products, those products better fit the moral standards as well,” Badiucao said.

If there is a timely moment to act and highlight the rights abuses in China, now is that time as the world’s attention is directed at Beijing because of the Olympics, said Asat, the Uighur human rights lawyer.

“When leaders prioritise national interest and choose silence in the face of injustice, then we will create a different kind of world where inequality triumphs over equality, exclusion over unity, bigotry over empathy,” she said.

“I hope the leaders reject that world and confront China.”