Inside the library where you can read in two countries at once

The US-Canada border cuts through the Haskell Free Library and Opera House, built more than 100 years ago.

Stanstead, Quebec, and Derby Line, Vermont – From the outside, the Haskell Free Library and Opera House looks like any other Victorian-style building from the early 20th century, complete with stained-glass windows, a grandiose façade and a slate roof.

But once inside, it doesn’t take long to see that the Haskell is unlike most places. That’s because the border between the United States and Canada bisects the building, leaving some readers and theatre-goers in one country – and the rest in another.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsColombia-Venezuela border reopening raises hopes, new questions

‘Hurting people’: The ‘cover-up teams’ operating on the US border

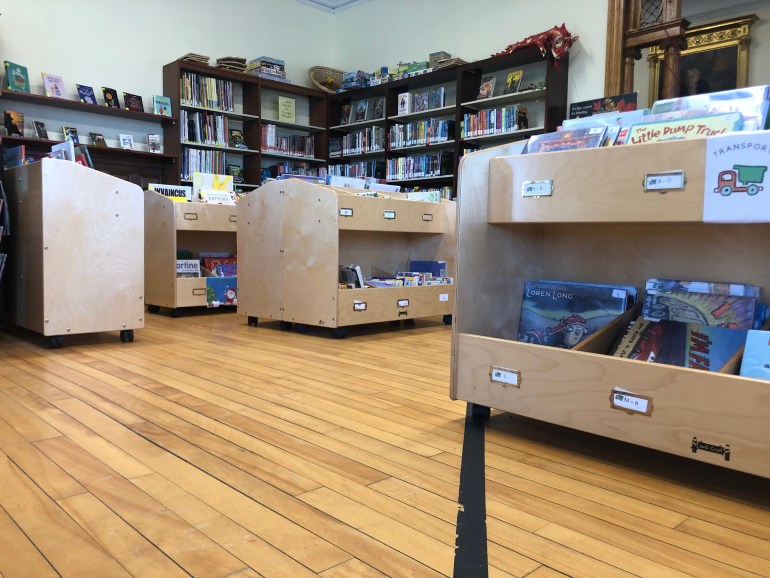

Most of the library books – primarily English and French offerings, as well as some in Spanish – are in Canada. In the adjoining Opera House, a majority of the 500 wooden seats, laid out over two floors, are in the US.

But the stage – which hosted its first performance in 1904 under a domed ceiling, chandelier and painted wall motifs – is in Canada.

The building also has two addresses – one Canadian, the other American – but only one entrance on the US side of the frontier. A line of black tape runs across the library’s main entrance hall and children’s reading room, delineating that dividing line.

“I don’t even realise it any more,” said Melanie Aube, the library’s current director, about working in a place that straddles an international border and draws tourists as well as residents from two neighbouring countries.

As borders become increasingly militarised around the world and a symbol of imposed divisions between communities, the Haskell stands as a testament to a time when people moved freely in this rural region, between the Canadian province of Quebec and the US state of Vermont.

And that is by design.

First opened in 1905, a year after the Opera House, the library was the brainchild of a wealthy local woman named Martha Haskell, who purposely built it in the US and Canada in a show of solidarity between residents of the then-porous border area.

For decades, Canadian and American citizens frequently crossed into each others’ countries to go to school, attend church, and even marry. Haskell’s goal was to “cheat” the border, said a young library tour guide, pointing to a large portrait of the founder in the entrance hall.

For many years, the actual dividing line became a sort of curiosity, raising questions about where Canada began and the US ended, and vice-versa.

“To me, as a child, and to the other children of the village, the iron post set in the curb of the wooden plank sidewalk, which marked the spot where Main Street ran into Canadian territory, was an object of interest and curiosity,” Austin T Foster, a resident of Derby Line, the rural Vermont town on the US side of the border, wrote in the Vermont Quarterly magazine in 1949 (PDF).

The small town on the Canadian side – Stanstead, Quebec – also has American roots as it was founded by “pioneers from New England in the 1790s”, the municipality says on its website.

Encompassing the historical villages of Beebe Plain, Stanstead Plain and Rock Island, Stanstead was once “a haven for smugglers and bootleggers”, the town says. “But the situation improved with the establishment of a customs station in 1821, the first in the Eastern Townships” region.

Back at the Haskell today, the reality of being in two countries at once brings its own challenges.

The line of tape on the floor was added to mark the exact border line after a fire decades ago set off a fight between insurance companies over who had to pay for damages, the tour guide explained.

Its location on the frontier also means that, despite a desire by staff to avoid politics, doing so has become increasingly difficult in recent years.

“Stop,” reads a Government of Canada border sign that faces Vermont, warning would-be border crossers that “not everyone is eligible to make an asylum claim” in Canada – a reference to increased asylum seeker arrivals from the US in recent years.

Another warning sign, translated into several languages including Russian, Romanian and Haitian Creole, tells people not to loiter at the frontier.

The library’s strategic location also led it to be the unwilling setting for a criminal scheme that saw a Canadian man sentenced to 51 months in prison in 2018 for smuggling more than 100 handguns from Vermont into Quebec.

Some of the weapons were stashed in small backpacks in a bin in the Haskell bathroom, US authorities said, and then retrieved and brought into Canada.

While the US-Canada land border has many heavily surveilled, formal crossings – including one just down the road from the library and opera house – long stretches of the 6,416km (3,987-mile) span are largely unmanned.

On a recent cold December morning, a Canadian police cruiser was parked near the Haskell, monitoring the border line, but stayed for only a few minutes before driving away.

To get into the building, Canadians can walk across the border and head for the front door on the US side. Passports aren’t required – there is no formal crossing here, after all – but the library tells visitors to expect their movements to be monitored – and to carry identification, just in case.

The library itself isn’t a border crossing, Aube stressed, and family reunions have been banned after relatives who were allowed to be in the US or Canada – but not both – began arriving by the dozens to share meals in the small space.

“It’s sad because it’s not something that we are happy to do,” Aube said about the ban. “We want those people to see their families, but if we want to keep our members that are donating for the library to stay open, we need to focus on them.”

Another major challenge is funding and maintenance, as the building is designated as a national historic site and, therefore, is subject to specific rules for renovations and upkeep under both US and Canadian regulations, Aube said.

And, despite its uniqueness, the Haskell’s staff readily admit that, like other libraries around the world, drawing visitors isn’t as easy as it may have once been – especially after the COVID-19 pandemic forced a months-long closure in 2020 and 2021.

Still, the library hosts weekly story hours for kids in a bright room filled with children’s books, as well as a French-language book club that draws some American Francophiles, Aube said. The Opera House also now organises film screenings.

Multiple generations of local families still use the library’s services, Aube added, and tourists come back year after year. “Because it’s special,” she said, when asked what draws people to the small library.

And as staff members and volunteers placed books back on the shelves and gave tours of the building that day in mid-December, a woman pushed through the front doors with a request.

“I need something to read,” she said.

The reply came a moment later: “You’ve come to the right place.”