How far are Ukraine and Russia from negotiations?

Talks are a distant prospect, experts warn, as the battlefield reality and winter will dictate both sides’ strategic calculus.

This past week, Ukrainian and Russian officials have made several public statements in an apparent willingness to re-engage in dialogue, blaming one another for stalling a possible negotiated solution after nearly nine months of fighting.

But experts have said the prospect of meaningful talks remains distant. Ukraine, they say, will seek to achieve more battlefield gains before heading to the negotiating table, while Russia hopes the impact of winter on Ukraine’s allies will fracture international support for Kyiv and weaken its resolve.

Keep reading

list of 3 items‘War of drones’: Ukraine troops push back Russians in Kherson

Russia coming under ‘heavy pressure’ in Ukraine, NATO chief says

“It makes sense to wait for now – Ukrainian forces now have momentum, they are advancing further in Kherson and that progress is going to set the stage and conditions for any discussion,” said William Taylor, a US former ambassador to Ukraine and vice president at the US Institute of Peace.

On Friday, the Russian army officially completed its retreat from the strategic Kherson city in the south, withdrawing to the eastern side of the Dnieper River, a reversal of its biggest military achievement since the start of the war. The southern regional capital was the only one it seized throughout the conflict.

“The problem with the negotiations now is that Russia has shown no serious proposals,” said Steven Pifer, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center on the US and Europe. “The demands of Russians have escalated, even if they have suffered bigger losses on the ground,” said Pifer, who served as the US ambassador to Ukraine from 1998 to 2000.

Despite losing territory, Russia yet insists Kherson is Russian land, following widely condemned and unrecognised annexations of four Ukrainian regions in September. “There can be no negotiations until Russia becomes more realistic and takes into account the reality of the battlefield,” he said.

‘Designed to maintain an alliance’

The annexation of Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhia and Kherson marked a turning point in Zelenskyy’s position towards talks. Following Russia’s move, he signed a decree ruling out any chance of holding negotiations with Putin. “We are ready for a dialogue with Russia, but with another president,” he said on October 4.

Zelenskyy had made a clear departure from a softer position adopted in March, when he had demanded Russian troops to withdraw to the pre-February invasion borders. But after the annexation move, he stepped up the conditions, asking the Russians to pull out from the whole of the country – Crimea and the eastern Donbas included.

His tone hardened as Ukrainian troops were enjoying more battlefield successes by the time of his decree. Moscow’s troops had failed to reach the capital Kyiv and Ukrainian forces were winning back swaths of territory in the northeast. Further eroding trust for talks, was the emergence of atrocities committed against Ukrainian civilians allegedly at the hands of Russian occupying forces.

On Monday though, Zelenskyy listed five conditions to sit at the table, including the restoration of Ukraine’s territorial integrity, the persecution of war crimes, and compensation for losses. These are not new requests from Zelenskyy, but this time, there was no mention of the earlier veto on talking with his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin. This somewhat softened stance came after a Washington Post report suggested US officials want Ukraine to signal an openness towards talks, but not necessarily start them.

Western leaders appear to be growing weary of increasing popular discontent. Soaring energy bills and spiralling inflation, which are to a degree consequences of the conflict, are creating unrest.

“It is important for the Americans that Ukraine has a reasonable position and the one that Zelenskyy outlined is designed to maintain that alliance,” said Taylor. “But American officials are not pressuring or suggesting the Ukrainians should move towards negotiations,” he added.

Crimea, a red line?

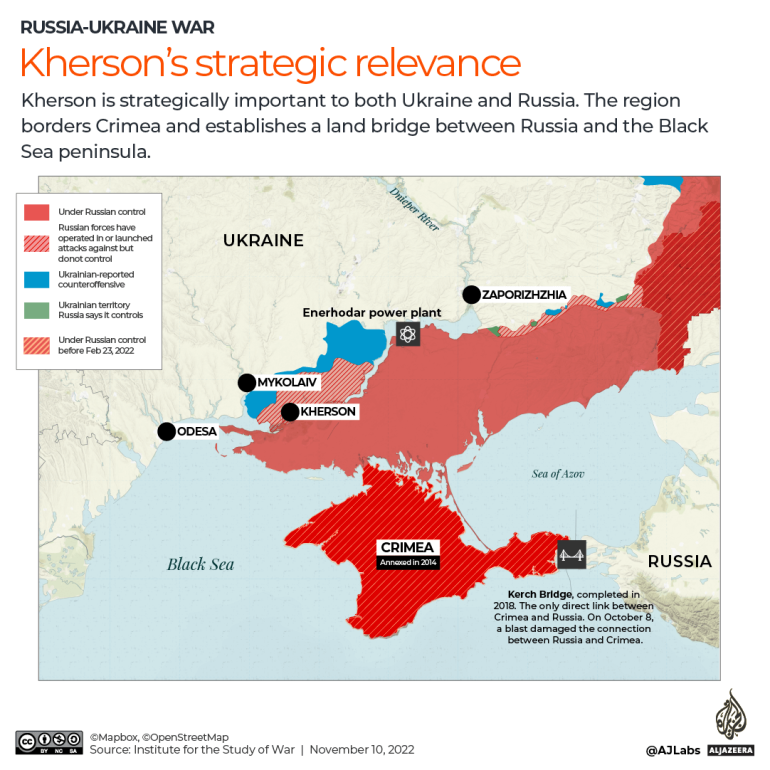

Looking ahead, the fate of the Kherson region could determine how quickly negotiations materialise, said Anatol Lieven, director of the Eurasia Programme at the Quincy Institute.

Ukraine’s southern region connects the mainland to Russian-annexed Crimea. The small isthmus linking the peninsula to Ukraine has turned into a key land corridor used to supply Russian troops.

“If Ukraine breaks through and captures not just the city, but the province of Kherson east of the Dnieper River, the hidden message of the [US President Joe] Biden administration is that they should stop and accept a ceasefire,” Lieven said.

This is because to move beyond Kherson, Lieven said, would be regarded as a threat to Crimea, with major consequences.

“There are strong indications that if Ukraine tries to take Crimea, then Russia’s use of nuclear weapons is very high – through a ladder of escalations,” he said.

Pifer disagreed, arguing that the US would support Ukraine trying to drive out an invading force.

However, Pifer noted, the Ukrainian army would rather aim at other targets than Crimea, which is militarily difficult to capture, but easy to defend, considering how narrow the stretch of land connecting the peninsula to the mainland is – about five to seven kilometres (three to four miles) wide.

“I also don’t think the US is saying don’t do things due to nuclear concerns. The threat of nuclear weapons is serious, Putin does not back down, but also Putin does want a nuclear war,” Pifer added.

A tale of two strategies

It’s too soon to speak about negotiations as both sides have too much to gain or to lose, said security expert at the European Council on Foreign Relations Rafael Loss.

After Russia’s retreat this week from Kherson city, Ukrainians are planning how to continue their goal of booting Moscow’s forces from the entire nation. “It is not unreasonable that other fronts collapse, like Kharkiv and Kherson did,” Loss added, pointing at possible offensives that would put pressure on Crimea and make progress in the northeast of the Donbas.

Kyiv will also need to consider its domestic context. After months of war and suffering, more than 85 percent of Ukrainians insist their nation should keep fighting rather than negotiating, a recent survey indicated.

Meanwhile, “Russia is banking more on a political, rather than military strategy,” and is likely to seize on the winter season to foment unrest in Europe and undermine Western support which has been fundamental to Kyiv’s counteroffensive, Loss said.

As temperatures fall, Russia has hoped more people will flee Ukraine to neighbouring countries, putting pressure on Europe. In addition, the economic and energy crisis could worsen should Moscow further weaponise gas flow to Europe or threaten to sabotage underwater cables and pipeline connections, Loss said.

“Once winter is gone then there will be a re-assessment of the situation.”