Canada unveils agreements to compensate Indigenous children

Human rights tribunal in 2016 said Canada had discriminated against Indigenous people in child and family services.

Canada has reached agreements-in-principle to compensate Indigenous children who were discriminated against and placed in the welfare system, the government has announced, after Indigenous advocates waged a years-long fight for justice and reform.

In a statement on Tuesday, the federal government said $15.75bn (20 billion Canadian dollars) would be allocated to First Nations children who were removed from their homes, as well as those who did not receive or faced delays in accessing services.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘No one will believe you’: When the RCMP abuses Indigenous girls

COVID outbreak: Indigenous community urges Canada to send in army

Canada court upholds Indigenous child compensation order

Another $15.75bn (20 billion Canadian dollars) will go towards long-term reform of the First Nations Child and Family Services programme, including funding for young adults ageing out of the child welfare system.

“For too long, the Government of Canada did not adequately fund or support the wellness of First Nations families and children,” Canada’s Minister of Indigenous Services Patty Hajdu said in the statement.

“First Nations children thrive when they can stay with their families, in their communities, surrounded by their culture. No compensation amount can make up for the trauma people have experienced, but these Agreements-in-Principle acknowledge to survivors and their families the harm and pain caused by the discrimination in funding and services.”

The announcement comes after Indigenous community advocates fought to get Canada to abide by a 2016 Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ruling that found the federal government had discriminated against Indigenous people in the provision of child and family services.

This discrimination pushed more Indigenous children into foster care, said the tribunal, which ordered Canada to pay each affected child $23,114 ($40,000 Canadian dollars), the maximum allowed under the Canadian Human Rights Act.

According to census data, just more than 52 percent of children in foster care in 2016 were Indigenous, while Indigenous children made up only 7.7 percent of the country’s total child population.

Canada admitted its systems were discriminatory but repeatedly fought orders for it to pay compensation and fund reforms, including in a federal court case it lost last year and sought to appeal, and an attempt it announced last year to overturn another tribunal decision ordering funding of capital assets and preventive services.

The reform deal announced on Tuesday includes $1,965 (2,500 Canadian dollars) in preventive care per child and provisions for children in foster care to receive support beyond age 18.

Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child & Family Caring Society, which brought the complaint to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, welcomed the agreements-in-principle on Tuesday as “an important first step”.

“There is an unquestionable need for actionable change. This Agreement-in-Principle, while an important first step, is a non-binding agreement,” Blackstock said in a statement (PDF), urging a binding deal to be finalised.

“It is only when that binding agreement has been written and signed by the Government of Canada and acted upon with great haste that First Nations children, youth and families will have a measure of assurance that actionable change is coming.”

Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN), an umbrella group that represents 49 First Nations in the province of Ontario, also welcomed the agreements-in-principle, saying a final settlement is expected to be completed by the end of March.

“What has been achieved deserves to be celebrated and will strengthen our Nations’ ability to care for our children and families,” NAN Deputy Grand Chief Bobby Narcisse said in a statement.

“The Agreement-in-Principle reached today is based on the recognition that the federal government has failed our youth and families for decades, but that Canada has partnered with First Nations and negotiated a healing path forward. This journey of long-term reform will be First Nations led and based on our inherent jurisdiction to care for our children.”

Canada continues to grapple with its history of colonialism and continuing policies that disproportionately harm Indigenous people, who accounted for 4.9 percent of the country’s total population in 2016.

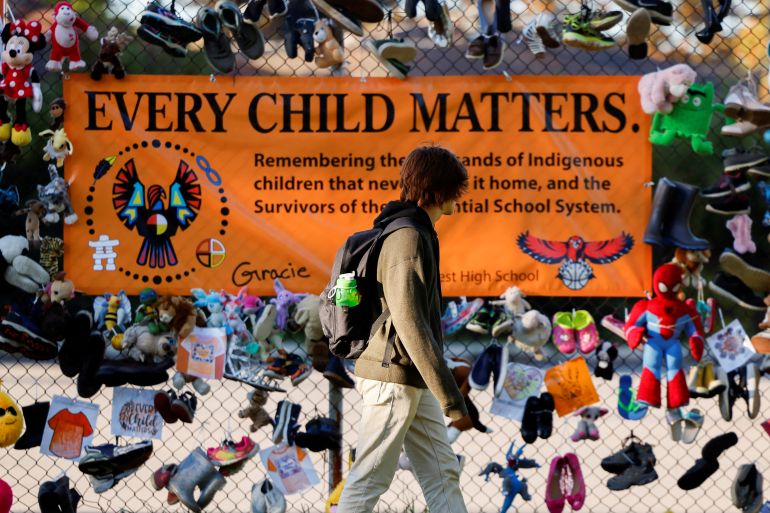

During the past year, hundreds of unmarked graves of Indigenous children have been uncovered at the sites of former “residential schools”, which the Canadian government forced more than 150,000 First Nations, Metis and Inuit children to attend for decades.

Established by the state and run by various churches, most notably the Roman Catholic Church, the forced-assimilation institutions were rife with psychological, physical and sexual abuse – and fuelled lasting, intergenerational trauma.

The Canadian government last month promised to release previously undisclosed residential school records, as survivors and their communities are pushing for answers and accountability for the abuses that took place.