Infographic: All you need to know about Germany’s elections

Germans go to the polls on Sunday. Here’s what you need to know about the parties, leaders, and key election issues.

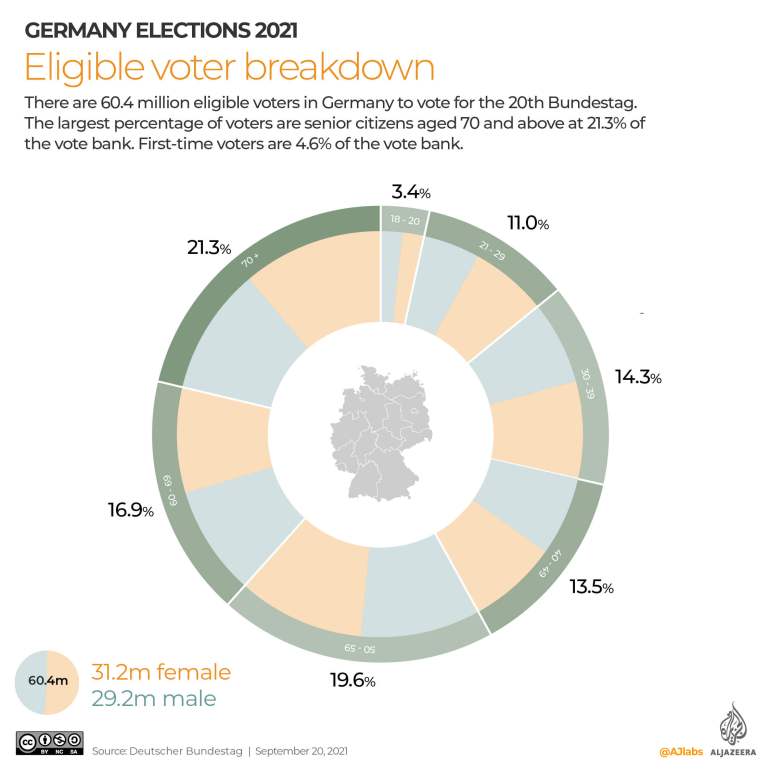

On September 26, 60.4 million eligible voters in Germany will head to the polls to choose the 20th Bundestag.

For the first time since German reunification, conservative Chancellor Angela Merkel will not be a candidate. She served as leader of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) for 20 years and has been in power for 16 years.

Keep reading

list of 1 itemThe campaign period has focused on issues such as the climate crisis and reducing carbon emissions, tackling the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic fallout it triggered, social welfare, innovation in digitalisation, and the government’s support for the European Union and NATO.

How these issues are tackled will depend on the new government, expected to be a coalition. According to international security consultancy RANE, opinion polls suggest a close tie between various parties, and negotiations to form a coalition might take time.

Three parties lead the polls: the conservative CDU and its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU), the progressive Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the environmentalist Greens.

Others, including the smaller, pro-business Free Democratic Party (FDP) and the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) are also running for seats, but it is unlikely any would reach the 5-percent threshold needed for representation.

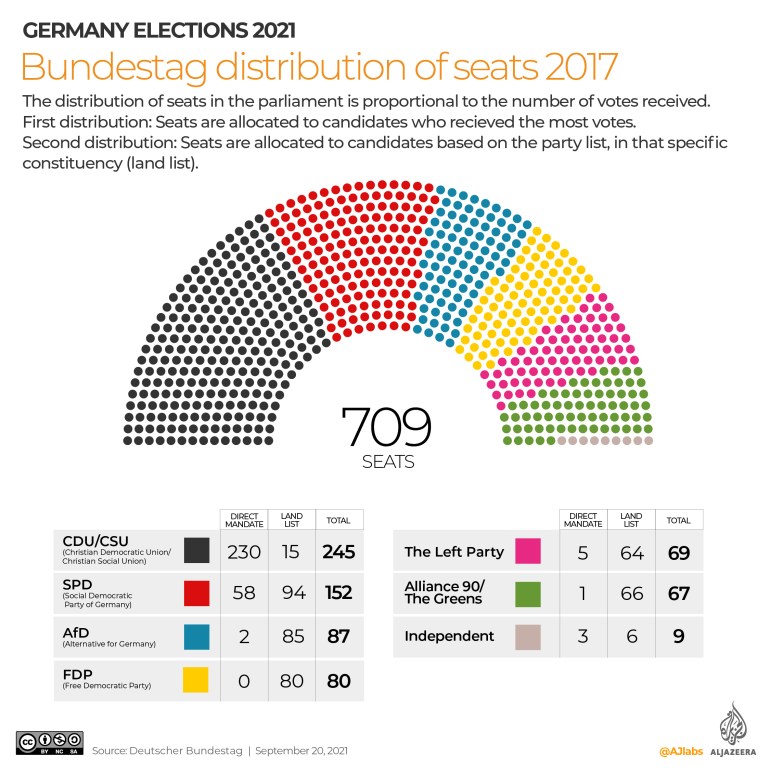

Germany’s current parliament

In 2013, it took almost three months to form a government. After the 2017 elections, negotiations took nearly six months.

The new government is likely to include moderate centre-left and centre-right parties.

Currently, the SPD leads in our polling aggregate by 4 points over the CDU/CSU after rising more than 9 points in the last eight weeks.

How does Germany vote?

The German parliament is made up of the Bundestag, the national parliament, which has federal legislative power and is elected directly by the German people, and the Bundesrat, which represents states (Lander).

Germany has a two-vote system in which eligible citizens vote twice, first for their representative and then for a party. Both votes do not need to be for the same party.

Directly elected candidates constitute 299 seats of the total, and another 299 are allotted based on the representation of the vote. The minimum requirement to secure a share of seats, a party must hold at least 5 percent of the overall vote.

The usual number of seats in the Bundestag is 598, but to ensure the share of seats reflects the proportion of the vote a party receives, 111 seats were added in 2017, taking the total to 709.

The federal chancellor is selected by all the members of the Bundestag. The chancellor is the head of the parliament and government. The president of Germany is a ceremonial position.

Who is voting?

According to the Federal Returning Officer, there are approximately 2.8 million first-time voters which account for 4.6 percent of the vote bank.

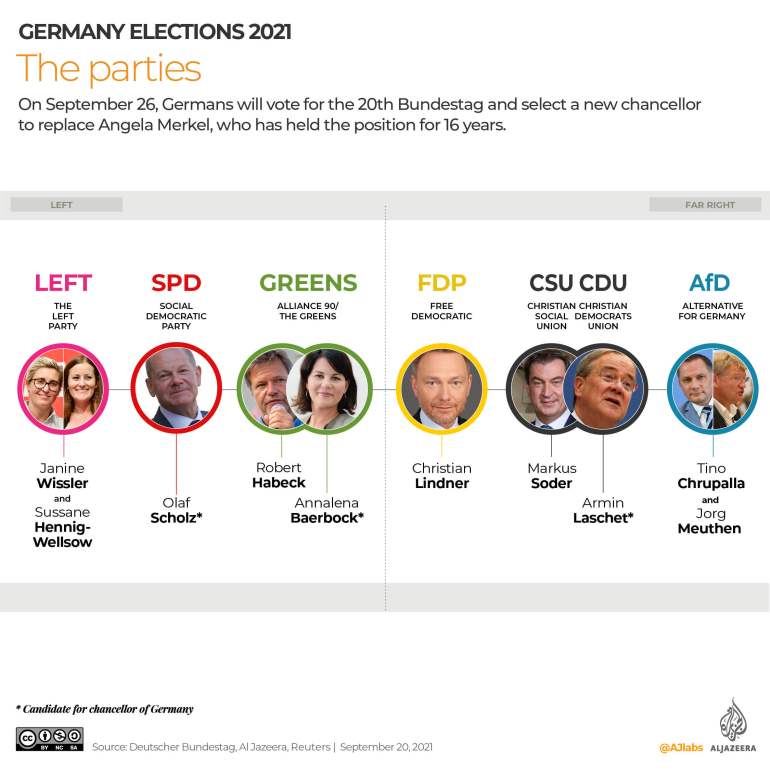

Who are the main leaders?

There are six leading parties in the Bundestag elections.

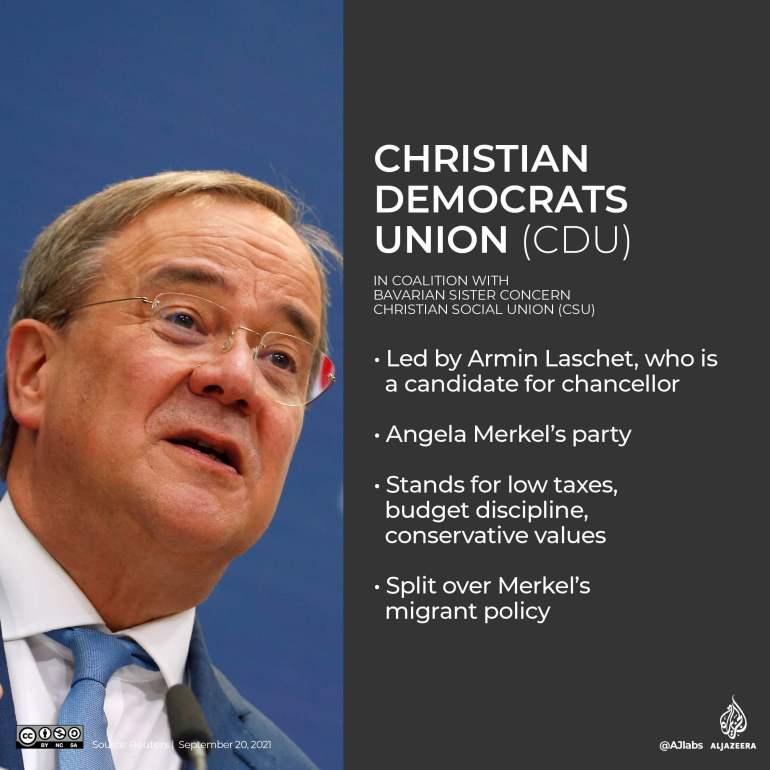

CDU/CSU led by Armin Laschet

The traditionally Catholic conservative bloc is made up of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU) and its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union. The “Union”, as it is usually called, stands for low taxes, budget discipline and conservative-liberal values. Members were deeply split over Merkel’s open-door migrant policy in 2015 which cost them votes but now, after 16 years in power, the party is looking for a way to reinvent its electoral success.

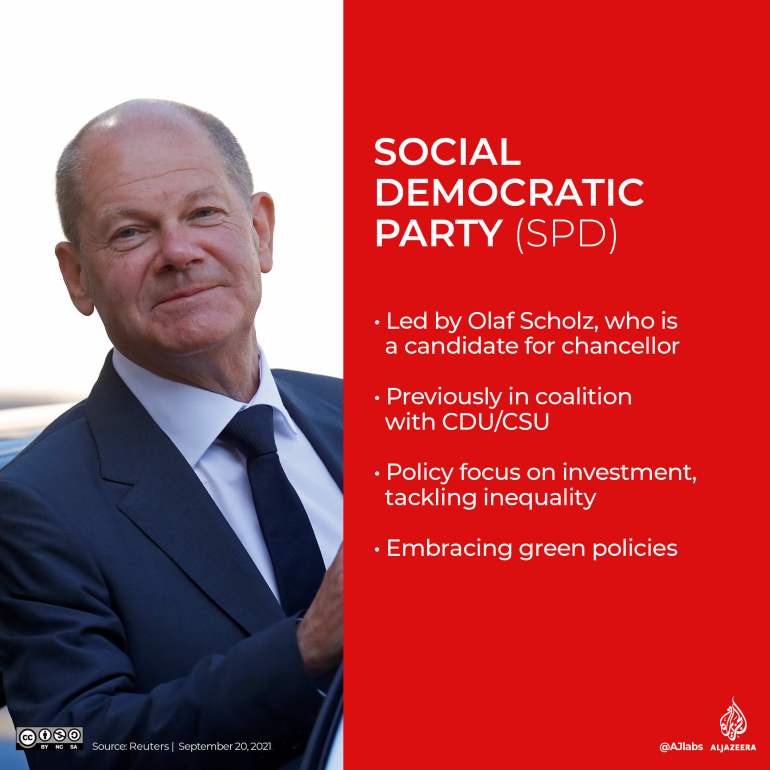

SPD led by Olaf Scholz

Germany’s oldest party and the main centre-left force. As the junior partner in a coalition with Merkel’s conservatives for 12 of the last 16 years, the SPD has struggled to carve out a clear identity for itself. Its policy focus is on investment and tackling inequality and the party has recently embraced more green policies.

The leadership duo of Saskia Esken and Norbert Walter-Borjans pulled the party left after taking over in 2019, but it is the candidacy of centrist Finance Minister Olaf Scholz that has given the party a late poll boost.

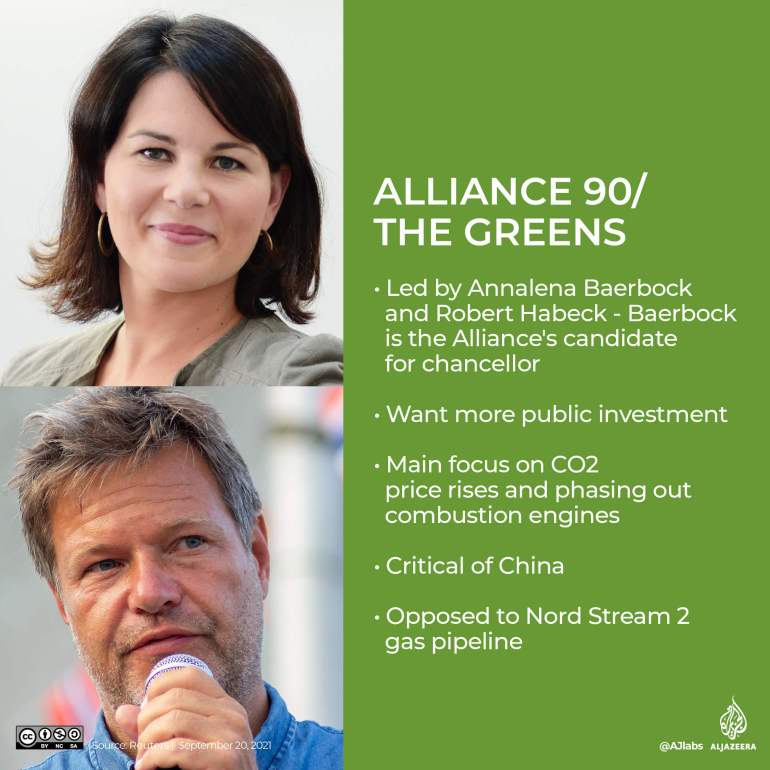

Greens led by Annalena Baerbock

Born out of the pacifist movement of the 1960s, the party first took a role in government in 1998, sharing power with SPD Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder. Under the leadership duo of Annalena Baerbock and Robert Habeck, the Greens have widened their appeal by developing clearer social and economic policies, such as reforming strict fiscal rules to allow more public investment. This complements their main focus on tackling climate change which they aim to achieve through faster CO2 price rises and phasing out combustion engines. It is critical of China and opposes the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline.

FDP led by Christian Lindner

Dubbed the party of doctors and dentists, the FDP campaigns for low tax and deregulation. Often kingmaker, the party has shared power with both conservatives and the SPD in the last 70 years. Current policies are closer to those of the CDU/CSU. They want to return to a binding debt break and oppose a eurozone fiscal union. On the environment, they prefer incentives through CO2 emissions trading schemes.

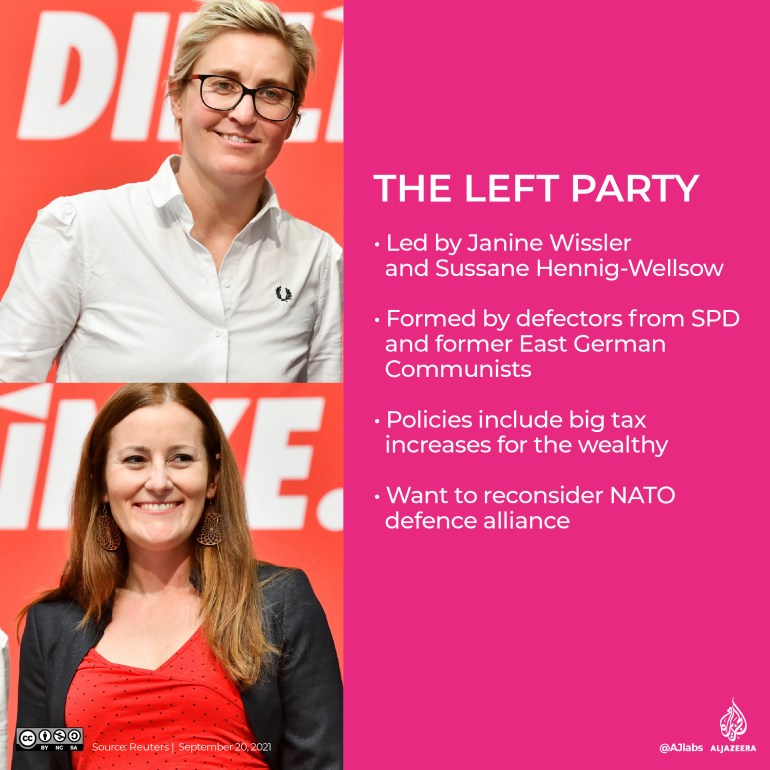

Left led Janine Wissler and Sussane Henning-Wellsow

A leftist party formed by defectors from the SPD and the remnants of East German communism, it has struggled to attract broad voter support. Policies include big tax increases for the rich and rethinking the NATO defence alliance.

AfD led by Joerg Meuthen and Tino Chrupalla

Set up as an anti-euro party in 2013 at the height of the eurozone debt crisis, it has removed its leadership team several times and morphed into an anti-immigrant grouping with far-right members among its ranks. The party also hosts climate change and COVID-19 deniers. The AfD capitalised on the 2015 migrant crisis to become the third-biggest party in the 2017 election and is the official parliamentary opposition.