New search begins for residential school graves in Canada

More than 1,200 unmarked graves were discovered this year at former forced-assimilation institutions for Indigenous children.

Warning: The story below contains details of residential schools that may be upsetting. Canada’s Indian Residential School Survivors and Family Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day at 1-866-925-4419.

Indigenous community leaders have begun searching for more unmarked graves at the site of a former boarding school for Indigenous children near Toronto, Canada, as calls to uncover the full scope of abuses linked to the country’s decades-long “residential schools” system continue.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsCanada: 182 unmarked graves found at another residential school

Will Canada face criminal charges for residential school abuses?

Canada’s Residential School Legacy

The search began on Tuesday at the former Mohawk Institute Residential School site in Brantford, Ontario – one of Canada’s oldest and longest-running such institutions.

It is one of dozens of searches that are ongoing or planned across the country following the discoveries of more than 1,200 unmarked graves at former residential schools in British Columbia and Saskatchewan this year.

“This is the first step in our journey to bring our children home,” Mark Hill, elected chief of the Six Nations of the Grand River, said during a news conference, as reported by CBC News.

“Although this will undoubtedly be a difficult process, Six Nations hopes that we as a people may

heal together by finally bringing our children home,” the community also said in a statement earlier on Tuesday.

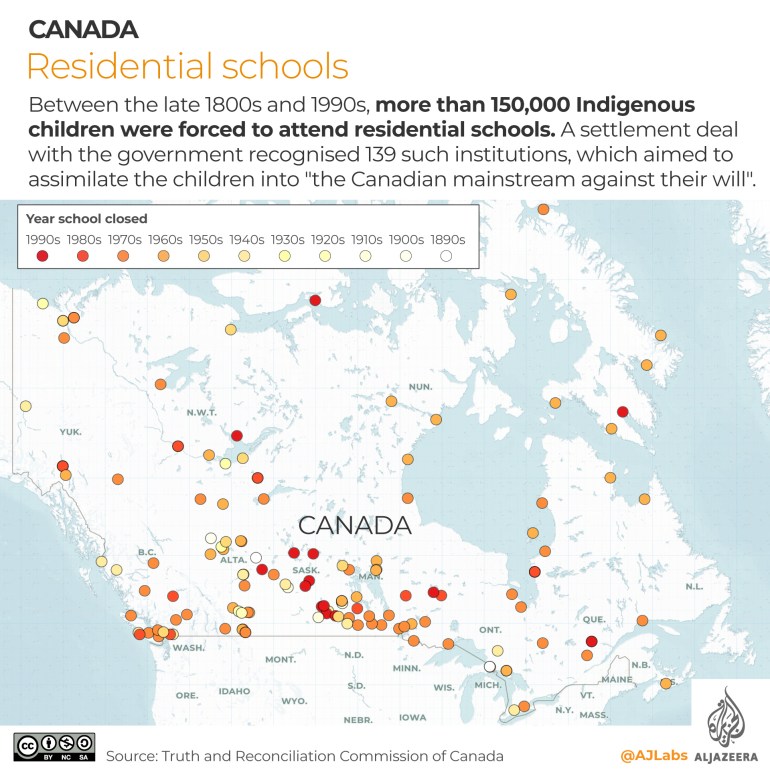

The Canadian government forced more than 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Metis children to attend residential schools between the late 1800s and 1990s.

The children were stripped of their languages and culture, separated from siblings, sent hundreds of kilometres away from home, and subjected to psychological, physical and sexual abuse. Thousands are believed to have died.

A federal commission of inquiry into the institutions, known as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), concluded in 2015 that Canada’s residential schools system amounted to “cultural genocide”.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has pledged financial aid and other support to help Indigenous communities find more unmarked graves and address the system’s lasting harms.

“We must all learn about the history and legacy of residential schools. It’s only by facing these hard truths, and righting these wrongs, that we can move forward together toward a more positive, fair, and better future,” Trudeau said in a statement on September 30, Canada’s first-ever National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

But Indigenous advocates say the government has failed to implement most of the TRC’s Calls to Action, and they also say current policies continue to disproportionately harm Indigenous children in Canada.

Indigenous communities, which have been reeling since the first discovery of 215 Indigenous children’s remains at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia in late May, also are calling on the Catholic Church to release all its records related to residential schools.

Meanwhile, some leaders have demanded that criminal charges be laid against the federal government, the church, as well as any individual abusers who are still alive.

The search at the Mohawk Institute Residential School site began following months of planning, including police training of local First Nation community members to use ground-penetrating radar to scan some 500 acres (202 hectares) at the site, said Hill, the chief.

“We have finally made it to this day where we are ready to begin the search,” he said.

“Survivors have been telling us for years the stories of what happened to them in the so-called schools. This investigation and the important work that comes with it is for survivors and is led by survivors.

“For many, this day has been long awaited, but also brings with it a stark reminder of the atrocities that were committed against our people in these institutions.”

The search and analysis of the results could take up to two years.

The Brantford school in 1885 became part of a network of 139 residential schools opened across Canada. An estimated 90 to 200 students were enrolled in it each year before it closed in 1970.