Landmark anti-nuclear treaty enters into force

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is now international law, but top powers still refuse to join the accord.

The first-ever treaty to ban nuclear weapons has entered into force, an historic step marred by the lack of signatures from the world’s major nuclear powers.

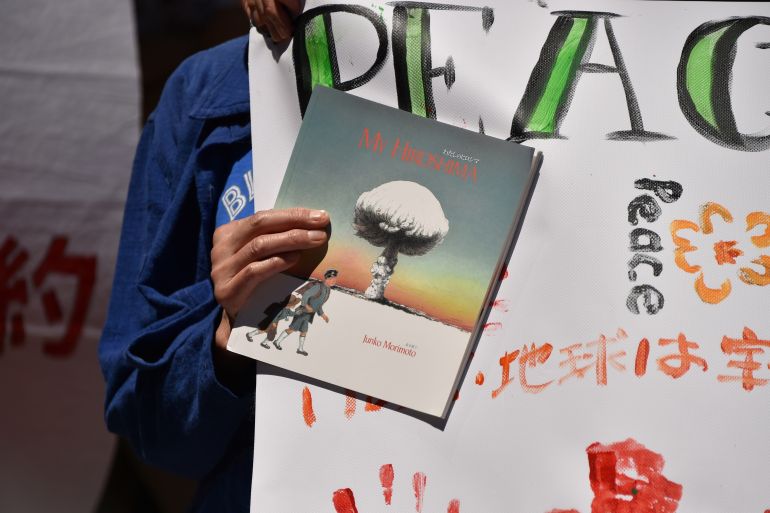

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons became part of international law on Friday, culminating a decades-long campaign aimed at preventing a repetition of the United States atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of WWII.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsCan the UN’s new treaty abolish nuclear weapons?

Nuclear weapons are finally outlawed, next step is disarmament

The treaty seeks to prohibit the use, development, production, testing, stationing, stockpiling and the threat of nuclear weapons. It also requires parties to promote the treaty to other countries.

But getting all nations to ratify the treaty requiring them to never own such weapons seems daunting, if not impossible, in the current global climate.

When the treaty was approved by the United Nations General Assembly in July 2017, more than 120 approved it. But none of the nine countries known or believed to possess nuclear weapons — the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, China, France, India, Pakistan, North Korea and Israel — supported it, and neither did the 30-nation NATO alliance.

Japan, the world’s only country to suffer nuclear attacks, also does not support the treaty, even though the aged survivors of the bombings in 1945 strongly push for it to do so. Japan on its own renounces the use and possession of nuclear weapons, but the government has said pursuing a treaty ban is not realistic with nuclear and non-nuclear states so sharply divided over it.

Nonetheless, Beatrice Fihn, executive director of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize-winning coalition whose work helped spearhead the treaty, called it “a really big day for international law, for the United Nations and for survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki”.

GOOD MORNING WORLD!

Today, nuclear weapons are banned. There’s no going back from this point, the #nuclearban will only grow stronger from now on.

The ban is the future. pic.twitter.com/Fpex7qFopW

— Beatrice Fihn (@BeaFihn) January 22, 2021

Fihn told The Associated Press news agency 61 countries had ratified the treaty as of Thursday.

The treaty received its 50th ratification on October 24, triggering a 90-day period before its entry into force on January 22.

Fihn said the treaty is “really, really significant” because it will now be a key legal instrument, along with the Geneva Conventions on conduct towards civilians and soldiers during war and the conventions banning chemical and biological weapons and land mines.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said the treaty demonstrated support for multilateral approaches to nuclear disarmament.

“Nuclear weapons pose growing dangers and the world needs urgent action to ensure their elimination and prevent the catastrophic human and environmental consequences any use would cause,” he said in a video message.

Today, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons enters into force.

This is a major step toward a world free of nuclear weapons.

I call on all countries to work together to realize this vision, for our common security and collective safety. pic.twitter.com/ybDamSdCZs

— António Guterres (@antonioguterres) January 22, 2021

Pope Francis heralded the treaty’s enactment during his general audience on Wednesday.

“This is the first legally binding international instrument explicitly prohibiting these weapons, whose indiscriminate use would affect a huge number of people in a short time and would cause long-lasting damage to the environment,” Francis said.

Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association, said the treaty’s arrival was an historic step forward in efforts to free the world of nuclear weapons and “hopefully will compel renewed action by nuclear-weapon states to fulfil their commitment to the complete elimination of nuclear weapons.”

A turning point in the long struggle against the Bomb: the TPNW enters into force Jan. 22. "The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons At A Glance" via the Arms Control Association #nuclearban https://t.co/vXni6RC5bK pic.twitter.com/OwMxJW3X5K

— Arms Control Assoc (@ArmsControlNow) January 21, 2021

Fihn said in an interview the campaign sees strong public support for the treaty in NATO countries and growing political pressure, citing Belgium and Spain.

“We will not stop until we get everyone on board,” she said.