Lebanese officials deflect blame as anger grows over Beirut blast

Ministers, port officials and judges trade blame as Lebanon begins probe into cause of deadly explosion.

![Lebanon''s capital Beirut shaken by massive explosion [Timour Azhari/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/99d7824369f944c3a67ea8a416fc833e_18.jpeg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

Beirut, Lebanon – A government-led investigation is under way in Lebanon to probe the cause of the massive explosion that ripped through the capital, Beirut.

The government announced on Wednesday that those responsible for guarding and storage at Beirut’s port – the epicentre of the blast – would be placed under house arrest “as soon as possible,” after the disaster left at least 137 dead and 5,000 wounded.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsParallel seasons: How Lebanon hides from reality

Lebanon’s FIBA World Cup journey is about much more than basketball

Justice for the Beirut blast can help avert Lebanon’s collapse

Damages from the explosion, which officials have linked to some 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate stored at the port, may be worth up to $15bn, Beirut Governor Marwan About said.

As the debris is cleared, anger has turned to rage after revelations that officials knew the highly volatile material had been stashed at Beirut’s port for more than six years.

A top-trending hashtag in Lebanon on Wednesday was #علقوا_المشانق (prepare the gallows).

Ramez al-Qadi, a prominent TV anchor, tweeted: “Either they keep killing us or we kill them.”

As heat rises around the country’s decision-makers, some have sought to deflect blame onto other branches of the state – including Lebanon’s judiciary.

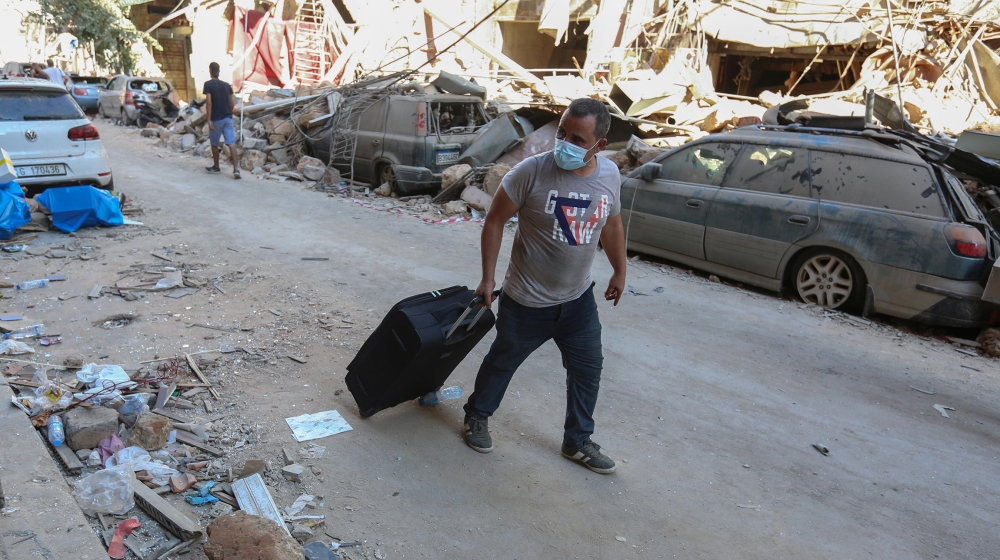

![Aftermath of Beirut explosion [Timour Azhari/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/a8b5cf77bd85401b8a3937a3022a745e_18.jpeg)

Public Works Minister Michel Najjar told Al Jazeera that he had only found out about the presence of the explosive material stashed in Beirut’s port 11 days before the explosion, through a report given to him by the country’s Supreme Defense Council. He had taken over the post six months earlier.

“No minister knows what’s in the hangars or containers, and it’s not my job to know,” Najjar said.

The minister said he followed up on the matter, but in late July, Lebanon’s government imposed a new lockdown amid a rapid increase in new COVID-19 cases. Najjar eventually spoke the general manager of the port, Hasan Koraytem, on Monday.

He said he asked Koraytem to send him all the relevant documentation, so that he could “look into this matter.”

That request came too late. The next day, just after 6pm (15:00 GMT), a warehouse at the port exploded, gutting the harbour and wrecking large parts of Beirut.

Najjar said he learned on Wednesday that his ministry had sent at least 18 letters to the Beirut urgent matters judge since 2014, asking for the goods to be disposed of. Najjar declined to provide the documents to Al Jazeera, citing a continuing investigation into the cause of the explosion.

“The judiciary didn’t do anything,” he said. “It’s negligence.”

But Nizar Saghieh, a leading Lebanese legal expert and founder of NGO Legal Agenda, said the “primary legal responsibility here is on those tasked with overseeing the port – the port authority and the public works ministry, as well as Lebanese Customs.”

“It is certainly not up to a judge to find the safe place to house these goods,” he told Al Jazeera.

Popular scepticism

Many angry Lebanese are demanding accountability and answers as to how and why 2,750 tonnes of highly explosive material was stored near residential Beirut for more than six years.

Management of the port has been split between a range of authorities. The port authority runs the operation of the port, and its work is overseen by the public works and transport ministry.

Lebanon’s customs agency nominally controls all goods that enter and exit the country, while the Lebanese security agencies all have bases at the port.

Few Lebanese feel confident they will see justice for this latest disaster in the country’s history, pointing to the lack of official accountability for the period of rampant corruption and mismanagement in the years after the country’s civil war.

Prime Minister Hassan Diab has promised this time will be different.

He is heading an investigation committee that includes the justice, interior and defence ministers and the head of Lebanon’s top four security agencies: the Army, General Security, Internal Security Forces and State Security.

The committee has been tasked with reporting its findings to Cabinet within five days, and Cabinet, in turn, will refer those findings to the judiciary.

In the meantime, officials in the executive authority, including Najjar, a minister in Diab’s government, have attempted to cast suspicion on Lebanon’s judiciary.

The case against the judiciary

The ammonium nitrate that blew up on Tuesday arrived in Beirut, reportedly by chance, on board a vessel facing technical issues in September 2013.

By 2014, the cargo had been unloaded and stored at Hangar 12 at Beirut’s port – now a deep crater filled with turquoise seawater.

Public documents verified by Al Jazeera show that Lebanese Customs sent six letters to the Beirut Urgent Matters Judge between 2014 and 2017, urging the judge to get rid of the “dangerous” material by either exporting it, re-selling it or handing it to the Army.

|

|

Badri Daher, the director-general of Lebanese Customs, said on Wednesday that the judiciary did not act, and blamed the institution and the port authority for failing to get rid of the goods.

Najjar echoed Daher, saying it was the judiciary, the port authority and, perhaps, security forces who were to blame.

“There is no negligence from the public works ministry,” he said of the portfolio that has been held by the Marada Movement since 2016.

“I’m surprised that they (the judiciary, port authority and security forces) didn’t find a way to deal with this for almost seven years. It was an accident waiting to happen,” he said.

Muddying the waters

Melhem Khalaf, the independently elected head of the Beirut Bar Association, said officials were undertaking a “pre-emptive attack to vilify the judiciary and muddy the waters on this case”.

“Since when are officials the ones who lay down verdicts?” Khalaf told Al Jazeera.

He said the government’s response to the disaster – forming a committee headed by establishment-backed politicians, and security forces who ultimately answer to those same politicians – is no way to find justice.

Lebanon’s Judges Club, a body independent of establishment political parties, also said justice should remain firmly in the courts.

Investigating the Beirut explosion is “not within the powers of any committee, no matter what it may be”, the club said in an implicit criticism of the government’s investigative committee.

On Tuesday, Khalaf filed a complaint with the highest judge in the land, Public Prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat, calling for him to seek the expertise of local and international experts – including engineers, explosives and chemicals experts – to assess the cause of the Beirut explosion.

“The time has come for officials to stop misleading the Lebanese people – there are dead and injured and missing, and the country has been burned,” Khalaf said.

“After all they have done, they are now coming to us and determining who’s responsible?”