Learning ‘pods’: a new solution to the coronavirus school crisis

Parents are banding together to form education pods for children to learn in groups, but not everyone can afford them.

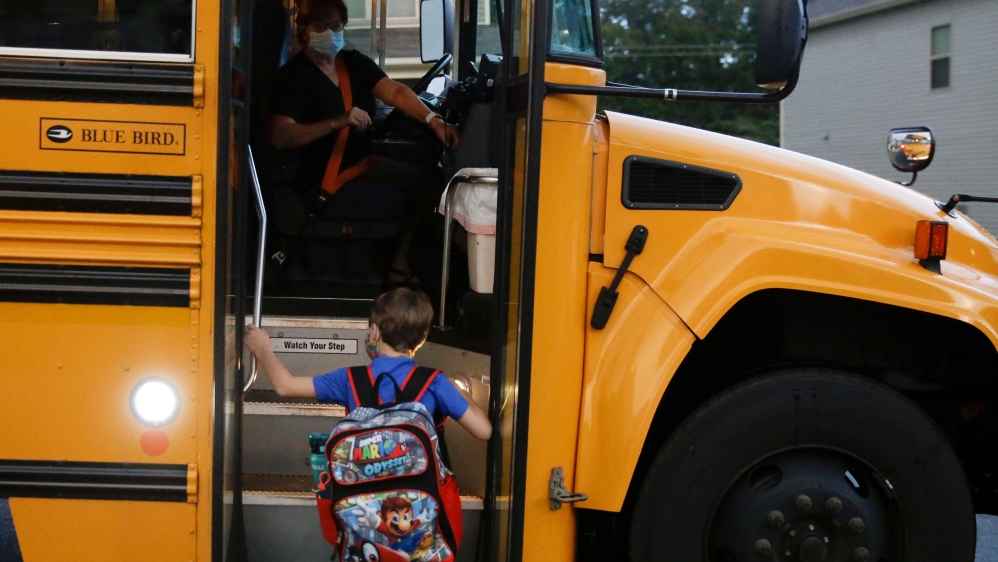

Starting first grade this year was supposed to be a big deal for Christy Teel’s seven-year-old son, Anderson, and she was going to take a commemorative picture with his backpack on, as he got on the school bus.

But hopes of schools reopening normally in her school district outside of Boston this academic year were dashed a few weeks ago, as cases of coronavirus continued to rise across much of the United States.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTrump ally Rudy Giuliani files for bankruptcy following defamation case

‘Insurrection’ should bar Donald Trump from US presidency, lawyers argue

Ex-Proud Boys leader Joseph Biggs sentenced to 17 years for US Capitol riot

Instead, Anderson will be doing a “hybrid” learning plan: going to school two days a week, and staying home for three days, where he will be learning online. And it remains unclear if the school bus service is going to be available.

“When I found out that my son was going to be home three days a week, I thought ‘I can’t do it, it’s going to be a battle,'” Teel said. She homeschooled Anderson in the spring when schools abruptly shut down, an experience which she says turned out to be a “colossal failure”.

Now she is racing to set up a “learning pod”, where she, together with other families with children of similar age, will hire a teacher who would supervise the online instruction as well as oversee other activities.

Teel’s plan is to have the pod meet for three hours a day, three times a week in one of the family homes. Depending on the teacher’s qualifications, it will cost between $50 and $150 an hour, which would be split among the families.

It is a concept that is spreading fast across the US as the pandemic drags on. Facebook groups have popped up connecting parents with one another and new websites have emerged offering to link families with instructors.

Parents say these pods will allow their children to remain on track academically, learn together, collaborate on activities and socialise with one another. It would also provide at least some childcare, so parents can go to work, or allow them to focus on their remote jobs at home.

Crystal Lucas, who has been a teacher in Ashland, Oregon, for more than 10 years, is planning on becoming a pod instructor and conduct private tutoring most afternoons, after her role as an elementary school teacher was “restructured” because of COVID-19 to include more hours for no additional pay.

She said she is now excited at the prospects of giving focused, individual teaching to a group of eight students, three times a week. She plans to charge $500 a day.

“I hope to show what a professional educator can do in a small group environment,” Lucas told Al Jazeera.

“There’s a dramatic difference in what I can offer, the gains we can academically make with a group of eight versus a group of 28,” she said.

Political hot button

The issue of school reopenings has turned into a political hot button topic in the US, one President Donald Trump sees as key to his re-election bid in November. He and his administration have been pushing for schools to reopen so that parents can return to work and the economy can get back on track.

But that policy has been at odds with health experts.

“There may be some areas where the level of virus is so high that it would not be prudent to bring the children back to school,” Dr Anthony Fauci, the country’s top infectious-disease expert, warned on Monday. “So you can’t make one statement about bringing children back to school in this country. It depends on where you are,” he said.

Though many schools, especially in smaller towns and in rural areas, plan on offering in-person instruction this term, albeit with mandates for masks, hygiene, screening and social distancing – most districts, especially in large and urban cities, will remain closed.

Chicago, the nation’s third-largest school district announced on Wednesday it would start the school year with online-only learning, leaving New York City as the only major urban area still intending to start some in-person classes.

A recent poll by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs found 80 percent of parents were at least somewhat concerned that school reopenings could lead to another surge in coronavirus cases and 31 percent thought schools should remain closed this autumn.

Last week, the American Federation of Teachers, one of the country’s largest teachers unions, issued a resolution authorising its members to strike if their schools plan to reopen without proper safety measures, and saying it will support any local chapter that decides to strike over reopening plans.

And across the country, teachers have staged car caravans and street marches demanding that health concerns and scientific findings on the virus dictate when and how schools reopen.

Trump, meanwhile, on Monday repeated his call for schools to open, tweeting: “OPEN THE SCHOOLS!”

OPEN THE SCHOOLS!!!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 4, 2020

Deepening inequalities

But the learning pods, which many parents are hoping would provide childcare as well as academic instruction for their children, also threaten to deepen existing inequities in access to education in the US.

“I think pods are a terrific option,” says Eliza Bobek, a clinical assistant professor at the Graduate School of Education at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell.

“My concern is that they are further creating equity issues based on what parents can afford to pay or dedicate time for,” Bobek told Al Jazeera.

According to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation poll, 49 percent of parents of colour worry about their children not having the technology needed for remote learning, compared with 17 percent of white parents. About 73 percent of parents of colour are concerned about their children falling behind academically this year.

But even among the more affluent parents who can afford pods and caregivers, there is concern that with schools shut and many sporting activities halted, children will be spending more time at home, often in front of a screen, missing out on critical interaction with their peers.

“We are seeing a tremendous increase in anxiety among children,” Shawn Nasseri, an ear, nose and throat surgeon in Los Angeles. Nasseri says a growing number of his child patients are suffering from adverse effects of not being able to socialise.

“Children are coming in with tic disorders, they are snorting, sniffing, swallowing, or moving their limbs repetitively,” Nasseri said. “Children need to interact with each other, it is critical for their social-emotional development and their learning.”

Regardles of how children are educated this academic year – in-person, online, or a mixture of the two – it will likely change the way many see schooling, said Jordan Shapiro, author of The New Childhood: Raising Kids to Thrive in a Connected World.

“I think it’s going to be an experiment, where a whole bunch of people will do random things and most of them are not going to work,” Shapiro tells Al Jazeera.

“The truth is children need a lot of guidance and a lot of mentorship, in order to get benefits,” he says. “Pods sound nice, in theory, but the bigger issue is whether or not there’s adult supervision, real construction of curriculum.”

Christy Teel, who works part-time from home as a lawyer, says she recognises her family’s privilege in being able to afford a pod instructor. Still, she says, she worries about her child’s wellbeing, as well as his academic prospects.

“I’m very concerned about the impact this is going to have on the children going forward, their friendships, relationships, and how they view school and their teachers,” Teel said. “I definitely think the kids are going to suffer, but I don’t know what else could be done.”