India’s coronavirus lockdown worsens access to mental healthcare

By not making arrangements for patients during lockdown, government may be violating its own landmark 2017 law.

New Delhi, India – Last month, during the first week of India’s coronavirus lockdown – the world’s largest and arguably the harshest – independent psychiatrist Maneesh Gupta was talking to a 15-year-old patient on the telephone.

Gupta’s clinic is located a station away from the Delhi metro and his patients are from a wider socioeconomic demographic than most.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsKashmir lockdown limits people’s access to mental healthcare

Locked down with abusers: India sees surge in domestic violence

Gupta was worried the condition of the teenager who lived in a village in the neighbouring Uttar Pradesh state, had taken a turn for the worse during the lockdown first imposed on March 25 and now extended to May 3.

Gupta prescribed medicines over the phone and gave his father a medical note. But the boy’s father was unable to source the drugs in nearby pharmacies.

The doctor finally found a pharmacy near the Delhi-Uttar Pradesh border which had the medicines, but the father was stopped by the police who refused to believe that a 15-year-old boy could have psychiatric issues.

But Gupta then remembered someone who could help.

“I asked the boy’s father about their relative in the police,” Gupta told Al Jazeera. “That policeman agreed and travelled 64km (40 miles) to pick up the medicines for the boy.”

But millions of other patients with mental illness across India may not be as fortunate.

“Another patient, a 64-year-old woman, reduced her medicines to half of the prescribed dose as she couldn’t travel to my clinic. But the reduction in dosage and uncertainty of lockdown led to anxiety, insomnia and restlessness.”

When the woman tried to reach Gupta’s clinic, her 25-kilometre (15 mile) journey involved multiple checks by “ill-informed, brutally disrespectful and uncooperative” policemen.

“Ultimately, the only patients I can help are those who have access to a vehicle,” Gupta told Al Jazeera.

‘Huge crisis’

According to India’s National Mental Health Survey 2015-16, 10.6 percent of India’s 1.3 billion population suffers from mental health disorders. The report notes that 80 percent of such patients are not under medical treatment.

This could be due to insufficient availability of mental health services, as well as the stigma associated with mental health disorders. There is also the fact that mental health problems often do not manifest physically.

One of Prime Minister Narendra Modi government’s most-lauded achievements has been the passage of the Mental Healthcare Act in 2017, which guarantees Indians the right to mental healthcare.

The law also discourages the earlier emphasis on institutionalising or incarcerating such patients, arguing instead for integrating patients within their communities.

However, by not making arrangements for patients during the lockdown, the government may be violating its own law.

Hospitals are open. But without access to public transport, travelling to hospitals is nearly impossible, especially for those who do not live in cities.

Many patients are registered with government hospitals and get their monthly dose of medicines there.

While the government does not keep records on the number of the patients needing medication, Dr Anirban Patra, who works in Kolkata’s Pavlov Hospital, told Al Jazeera he has seen a decrease in patient visits. “[It’s] fallen to 20 percent of what we see on a usual day”.

“Many of my patients get their medicines from the hospital. The nature of these medicines is such that you have to take them for a long time, then they are tapered off gradually if needed. Abrupt stops are harmful.”

Anjali, an NGO which works on the mental health of poor communities across West Bengal state, is coordinating the distribution of the medicines from hospitals.

Doctors say the patients who have been reintegrated into their communities after being admitted in institutions for treatment are the most vulnerable during the continuing lockdown.

“The logistics have proved to be a phenomenal challenge although we have secured police passes for movement,” Anjali’s founder Ratnaboli Ray, also a clinical psychologist and leading human rights advocate, told Al Jazeera.

“Our staff and volunteers are constantly stopped because policemen and officials on the ground are not aware of how essential a health service this is,” he said. “Systemically, this is a huge crisis.”

Experts say the disquiet and anxieties caused by the coronavirus pandemic and the consequent lockdown in itself could be a cause for a spike in mental disorders.

Limited access to medicines

The government of India is promoting telemedicine as a means of providing health services during the lockdown. This requires patients to either call a helpline number or access a phone application to order their medicines.

On March 25, the first day of India’s lockdown, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare issued telemedicine guidelines, which included a template for providing electronic prescriptions to those with mental illnesses.

Speaking to Al Jazeera, a government doctor at King George Medical University in Lucknow, who did not want to be named said the telemedicine facility had not yet started in his hospital and was expected to begin shortly.

“To be honest, our patients are mostly the rural poor,” he said. “They are finding it almost impossible to travel. And psychiatric medicines are not available everywhere.”

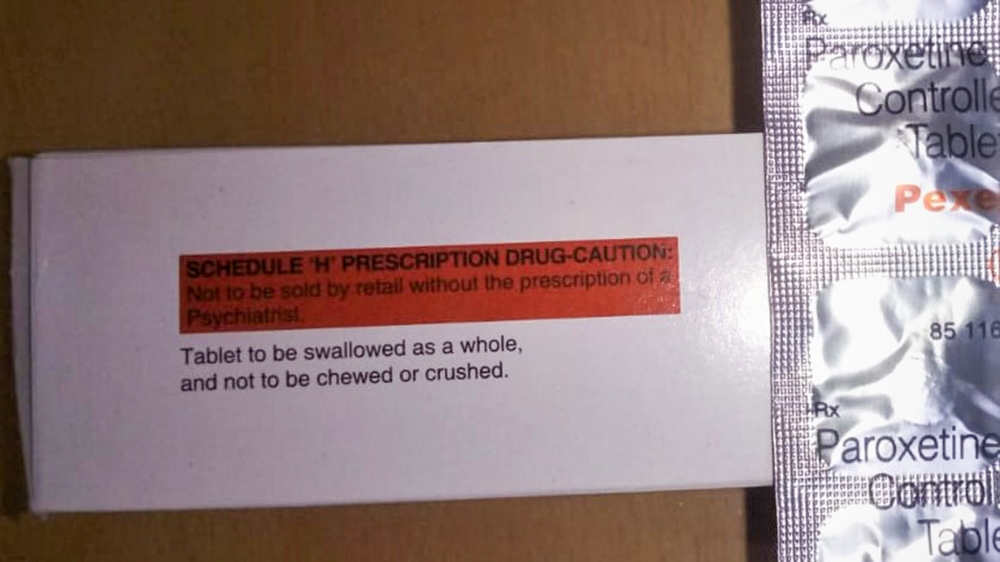

But even telemedicine prescriptions allow patients to buy a limited number of psychiatric drugs, most of which cannot be sold over the counter. In order to get the full spectrum of drugs a hard copy prescription is needed, which the patient has to obtain in person from a hospital doctor.

And despite India’s impressive network of mobile phones, experts say telemedicine is an impractical solution in a country facing poverty and illiteracy.

“For telemedicine, there has to be a tele,” said Ray. “Many of them [patients] are eating rice with salt once a day. They don’t even have money for medicines.”