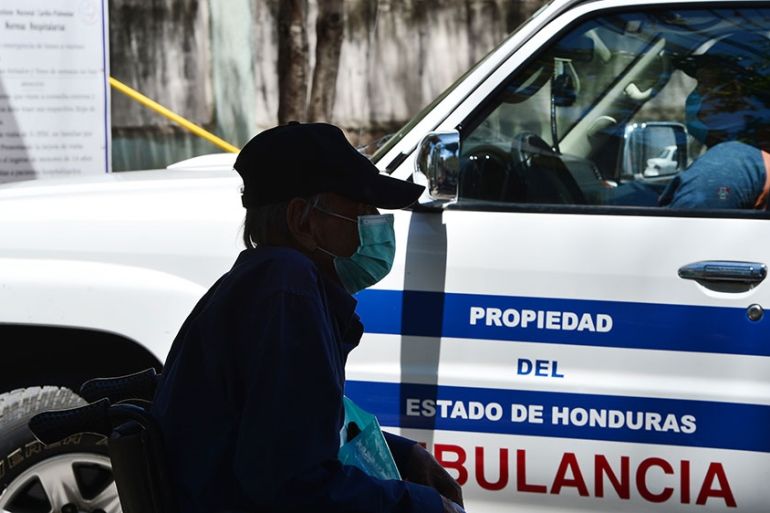

Coronavirus crisis exposes another pandemic in Honduras: Analysts

Analysts worry corruption will exacerbate the crisis facing Honduras’s already strained healthcare system.

As the number of COVID-19 cases in Honduras climbed to at least 67 and the country announced its first death this week, analysts warned of a second pandemic that could exacerbate the public health crisis: “corruption”.

“We have a health system that is very fragile. Unfortunately, it has not been a priority of the governments in the history of our country,” said Carlos Hernandez, director of Tegucigalpa-based transparency NGO Association for a More Just Society (ASJ). “And then the other element is obviously corruption.”

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsHow are countries in Latin America fighting coronavirus?

Indigenous race into Ecuador’s Amazon to escape coronavirus

Honduras has one of the weakest healthcare systems in the world and is ill-prepared to confront an epidemic, according to Johns Hopkins University’s Global Health Security Index. The country spends only about 8.5 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on healthcare, much less than the regional average of 14 percent. Corruption in the healthcare system, including embezzlement of public funds and schemes to buy overpriced medicine and equipment, only worsens the problem.

Honduras’s healthcare system has reached the edge of collapse in recent years after chronic underfunding from the government and a series of corruption scandals that have drained what little public funds do exist. Hospitals often lack medicine, bed space and basic supplies, a situation that spells disaster for a growing pandemic.

To make matters worse, any response to the spreading virus could be an opportunity to further pilfer government coffers, analysts say.

“History tells us that times of emergency are unfortunately opportunities for the corrupt,” said Hernandez.

Years of corruption, mismanagement

Corruption had been eating away at the Honduran healthcare system for years. But in 2015, one scandal tipped the scales and drove Hondurans to the streets.

The Honduran Public Ministry, a government institution that investigates crimes related to the public interest, revealed an elaborate network of sham companies used to embezzle hundreds of millions of dollars out of the healthcare system.

While the rich bought spacious mansions and flashy cars, average Hondurans did not have enough medicine or a clean bed at a hospital. Since then, more than 45 people have been accused of crimes and 10 people have been convicted in the case.

“Corruption in the healthcare system is a brotherhood – an alliance of bad politicians, bad businessmen and bad workers. They are the ones who have looted the health system,” said Hernandez.

Some of the money ended up funding the first presidential campaign of current President Juan Orlando Hernandez, whose presidency has been tainted by many scandals, most recently the New York drug trafficking conviction of his brother.

“In the case of Honduras and Central America, corruption is widespread,” said Adriana Beltran, director of the citizen security programme for the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA). “It’s not just about the cases we’ve heard of recently of top-level politicians involved in drug trafficking, but also how it impacts daily lives and the ability to access adequate healthcare.”

Other corruption scandals in the country’s healthcare industry have included mismanagement of funds, fake purchases of medicine and alleged attempts to privatise the healthcare industry.

In April 2019, Hondurans’ anger with widespread corruption once again exploded into weeks-long mass mobilisations to protest against two decrees to possibly privatise the country’s healthcare and education systems.

“We have a healthcare system that collapsed,” said Suyapa Figueroa, president of the Honduran Medical College who participated in the marches. “It collapsed in part because of corruption. Corruption has been and continues to be one of the biggest problems in our country.”

President Hernandez rejected accusations of attempts to privatise the healthcare and education systems. “The intention has always been to strengthen and improve education and public health and that it remains free for the Honduran people,” he said in May 2019. Still, the president revoked the contentious decrees in June.

Figueroa warns that the government could manipulate this public health crisis into another attempt to privatise the healthcare system. “Our problems are structural,” said Figueroa. “As long as we don’t change this harsh reality, the problem is going to continue.”

Corruption hard to spot in current crisis

On March 11, President Hernandez confirmed the first two cases of the coronavirus in the country.

“The detection of these two first cases shows that Honduras has the installed capacity and we have the necessary supplies to carry out the corresponding tests for any person suspected of coronavirus,” he said at a news conference. His administration has continued to assure Hondurans that they are prepared for what is to come.

Just two days later, on March 13, the Honduran Congress approved an emergency plan for more than $420m to build more hospitals and hire more healthcare professionals in response to the coronavirus.

Civil society is already vigilantly monitoring these actions for potential corruption, according to Hernandez of ASJ. But the current conditions in the country could make it more difficult to identify embezzlement or mismanagement.

In January, the government decided not to renew the mandate of an international anti-corruption body called MACCIH, which with the country’s attorney general’s office had been investigating Honduran elites, including a former first lady, who was convicted on corruption charges last year. The current government-imposed curfew and restrictions of press freedom have made it harder for journalists to obtain and share information. And since Congress approved the funds during an emergency, the executive branch has more discretion for spending.

“That has raised a lot of concern because it has been one way in which public funds were embezzled in the past,” said Beltran of WOLA. “With the quarantine that has been ordered, it makes it a lot harder for civil society and the press to do any kind of oversight.”

On March 17, the Honduran government sent its presidential plane to New York to buy biomedical equipment to address the coronavirus pandemic, including 140 respirator masks and 140 ventilator machines. But health experts feared the government was not consulting with proper health professionals about the types of equipment to buy, and some say the ventilators purchased will do little to help those with COVID-19.

“Now that it’s a life or death situation, the experts are the ones who need to lead,” she said. The Honduran Health Ministry did not respond to Al Jazeera’s request for comment by the time of publication.

Given the history of corruption in Honduras’s healthcare system, Villanueva and other members of civil society call for transparency during this crisis.

“There are many excuses that the corrupt can use and that’s what worries us: the lack of transparency in the way that they are handling the public health situation,” Villanueva said.