US axed CDC expert job in China months before outbreak: Reuters

Dr Linda Quick was a trainer of Chinese field epidemiologists who helped track, investigate and contain outbreaks.

Several months before the coronavirus pandemic began, the administration of US President Donald Trump eliminated a key American public health position in Beijing that was intended to help detect disease outbreaks in China, Reuters news agency has learned.

The American disease expert Dr Linda Quick, a medical epidemiologist embedded in China’s disease control agency, left her post in July, according to four sources with knowledge of the issue.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsLockdowns, closures: How is each US state handling coronavirus?

Coronavirus could destroy 10 million US jobs, economists fear

The first cases of the new coronavirus may have emerged as early as November, and as cases mounted, the Trump administration in February chastised China for censoring information about the outbreak and keeping experts from the United States from entering the country to help.

“It was heartbreaking to watch,” said Bao-Ping Zhu, a Chinese-American who served in that role, which was funded by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), between 2007 and 2011. “If someone had been there, public health officials and governments across the world could have moved much faster.”

Zhu and the other sources said Quick was a trainer of Chinese field epidemiologists who were deployed to the epicentre of outbreaks to help track, investigate and contain diseases.

As an American CDC employee, they said, Quick was in an ideal position to be the eyes and ears on the ground for the US and the rest of the world on the coronavirus outbreak and might have alerted them to the growing threat weeks earlier.

No other foreign disease experts were assigned to lead the programme after Quick left in July, according to the sources. Zhu said an embedded expert can often get word of outbreaks early, after forming close relationships with Chinese counterparts.

Zhu and the other sources said Quick could have provided real-time information to US and other officials around the world during the first weeks of the outbreak, when they said the Chinese government curbed the release of information and provided erroneous assessments.

Job discontinued

Quick left when she learned her federally funded post, officially known as resident adviser to the US Field Epidemiology Training Program in China, would be discontinued as of September, the sources said. The CDC said it first learned of a “cluster of 27 cases of pneumonia” of unexplained origin in Wuhan, China, on December 31.

Since then, the outbreak of the disease known as COVID-19 has spread worldwide, leaving more than 14,600 people dead, and overwhelming healthcare systems in some countries.

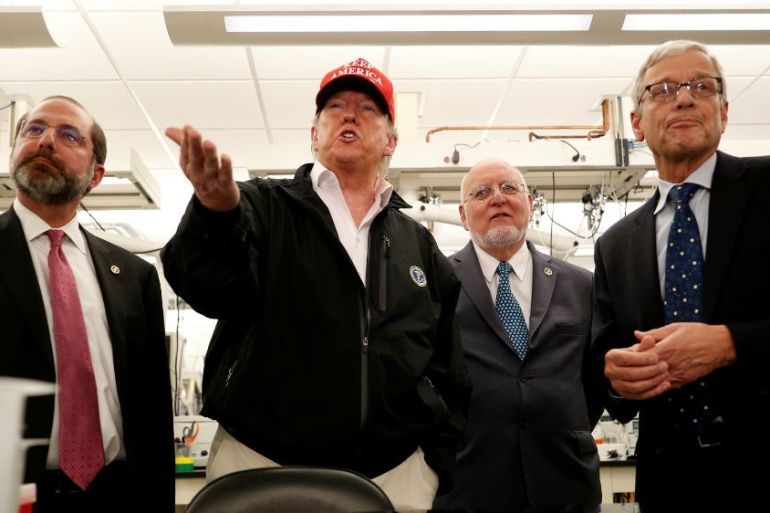

At a press briefing on Sunday, Trump dismissed the Reuters report as similar to other stories on the CDC that he described as “100 percent wrong”.

CDC Director Dr Robert Redfield said the agency’s presence was “actually being augmented as we speak,” without elaborating.

In an early statement to the news agency, the CDC said the elimination of the adviser position did not hinder Washington’s ability to get information and “had absolutely nothing to do with CDC not learning of cases in China earlier”.

The CDC would not make Quick, who still works for the agency, available for comment.

Asked for comment on Chinese transparency and responsiveness to the outbreak, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs referred Reuters to remarks by spokesman Geng Shuang on Friday. Geng said the country “has adopted the strictest, most comprehensive, and most thorough prevention and control measures in an open, transparent, and responsible manner, and informed the (World Health Organization) and relevant countries and regions of the latest situation in a timely manner.”

One disease expert told Reuters he was sceptical that the US resident adviser would have been able to get earlier or better information to the Trump administration, given the Chinese government’s suppression of information.

“In the end, based on circumstances in China, it probably wouldn’t have had made a big difference,” Scott McNabb, who was a CDC epidemiologist for 20 years and is now a research professor at Emory University.

“The problem was how the Chinese handled it. What should have changed was the Chinese should have acknowledged it earlier and didn’t.”

Alex Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), said on Friday that his agency learned of the coronavirus in early January, based on Redfield’s conversations with “Chinese colleagues”.

Redfield learned that “this looks to be a novel coronavirus” from Dr Gao Fu, the head of the China CDC, according to an HHS administration official, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Dr Redfield always talked to Dr Gao,” the official said.

HHS and CDC did not make Azar or Redfield available for comment.

Zhu and other sources said US leaders should not have been relying on the China CDC director for alerts and updates. In general, they said, officials in China downplayed the severity of the outbreak in the early weeks and did not acknowledge evidence of person-to-person transmission until January 20.

After the epidemic took off and China had imposed strict quarantines, Trump administration officials complained that the Chinese had censored information about the outbreak and that the US had been unable to get American disease experts into the country to help contain the spread.

The WHO secured permission to send a team that included two US experts, by the time they visited between February 16 and 24, China had reported more than 75,000 cases.

On February 25, the first day the CDC told the American public to prepare for an outbreak at home, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo accused China of mishandling the epidemic through its “censorship” of medical professionals and media.

Relations between the two countries have deteriorated since then, as Trump has labelled the coronavirus the “Chinese virus” – a description the Chinese have condemned.

Quick’s job was eliminated after the CDC moved over the past two years to reduce the number of US employees in China, the sources told Reuters.

“We had already withdrawn many technical public health experts,” the same expert said.

|

|

The CDC, however, disputed that staffing was a problem or that its information had been limited by the move. “It was not the staffing shortage that limited our ability,” it said.

The CDC team in Beijing now includes three US citizens in permanent roles, an additional US citizen in a temporary role, and approximately 10 Chinese nationals, the agency said. Of the US citizens, one is an influenza expert with expertise in respiratory disease. Coronavirus is not influenza, although it is a respiratory disease.

Personal ties

The CDC team, aside from Quick, was housed at US Embassy facilities. No American CDC staffer besides Quick was embedded with China’s disease control agency, the sources said.

Dr Thomas R Frieden, a former director of the CDC, said if the US resident adviser had still been in China: “It is possible that we would know more today about how this coronavirus is spreading and what works best to stop it.”

Dr George Conway, a medical epidemiologist who knows Quick and was resident adviser between 2012 and 2015, said funding for the position had been tenuous for years because of perennial debate among US health officials over whether China should be paying for funding its own training programme.

Yet, since the programme was launched in 2001, the sources familiar with it say, it has not only strengthened the ranks of Chinese epidemiologists in the field, but also fostered collegial relationships between public health officials in the two countries.

“We go there as credentialled diplomats and return home as close colleagues and often as friends,” Conway said.

In 2007, Dr Robert Fontaine, a CDC epidemiologist and one of the longest-serving US officials in the adviser’s position, received China’s highest honour for outstanding contributions to public health due to his contribution as a foreigner in helping to detect and investigate clusters of pneumonia of unknown cause.

But, since last year, Frieden and others said, growing tensions between the Trump administration and China’s leadership have apparently damaged the collaboration.

“The message from the administration was, ‘Don’t work with China, they’re our rival,'” Frieden said.

The White House did not immediately respond to a request for comment.