In Ethiopia, a heated political tug-of-war sparks security fears

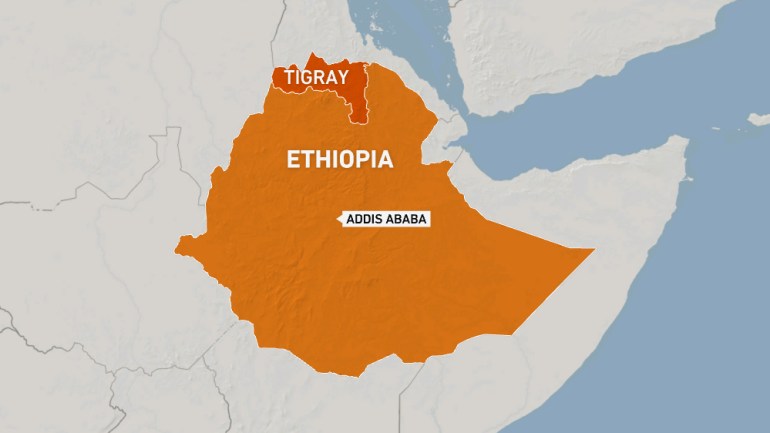

Concerns grow as bitter dispute between Abiy Ahmed’s federal government and Tigray regional leaders intensifies.

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia – Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has been locked in a bitter dispute with the political party that used to dominate the country’s politics for decades, raising questions about his ability to hold Ethiopia together through a fraught political transition.

On October 7, legislators at Ethiopia’s upper house of Parliament – known as the House of Federation (HoF) – voted to withhold budgetary subsidies to the Tigray regional state in the country’s north.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsEthiopia talks with Oromo rebel group end without deal for a third time

Abiy Ahmed’s imperial ambitions are bad news for Africa, and the world

Dashed hopes and limited aid trouble Tigrayans a year after Ethiopia truce

The move by the HoF, which is dominated by allies of Abiy, came two days after Tigray’s regional leaders – and Abiy’s political rivals – decided to recall their representatives at the federal level.

Tensions were already running high since September when the Tigray region held an election in defiance of a decision by central authorities earlier this year to postpone all parliamentary and regional elections scheduled for August due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Abiy’s opponents said the postponement was a move by the prime minister to prolong his rule and pressed ahead with the election, in which the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) – the dominant political force in the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a multi-ethnic, four-party coalition that had run the country for almost 30 years – won a landslide victory.

The TPLF had already split from the EPRDF in 2019 when it refused to merge along with the three other coalition parties into the newly formed Prosperity Party (PP) under Abiy.

The HoF, however, declared the September 9 vote null and void, indicating the new Tigray regional assembly will not be recognised by the federal government.

The latest moves, seen as part of a campaign of mutual de-legitimisation, have sparked fears the political turmoil could spiral into a security crisis, the latest challenge to the federal system that stitches Ethiopia’s more than 80 ethnic groups together.

Wondimu Asaminew, a former diplomat and currently the head of the Tigray Friendship Liaison Office based in the Tigray regional capital of Mekelle, is adamant the federal government in Addis Ababa is to blame for the current situation.

“Abiy’s team, from the start, had a strategy of trying to sideline, make irrelevant and even criminalise TPLF,” Wondimu said.

Wondimu was referring to the tense relationship between the prime minister and the TPLF dating back to April 2018, when Abiy assumed his post after weeks-long secretive deliberations within the EPRDF.

Taking office after months of anti-government protests, Abiy promised to solve the country’s deep ethnic and political divides and change the EPRDF’s repressive and violent image. In the first few months, he speeded up the political reforms started in the dying days of his predecessor, Hailemariam Desalegn. Political prisoners were released and opposition parties were allowed to operate, while Abiy even won a Nobel Prize for securing peace with neighbouring Eritrea.

The reform process saw the long-dominant TPLF being cast aside, as the Oromo and Amhara political wings of the EPRDF moved into the political centre stage – even as in recent months prominent Oromo figures have accused Abiy, an ethnic Oromo, of being a poor advocate for Oromo interests and sliding towards authoritarianism.

Ethnic Tigrayans make up about 6 percent of Ethiopia’s population, while ethnic Amharas and Oromos combined comprise some 65 percent of Ethiopia’s total population.

While Abiy’s and TPLF’s relationship was tense from the start, the merging of the EPRDF into the PP led to outright hostility between the two sides – and the postponement of the national elections added fuel to the fire.

“Abiy wasn’t ready to solve issues within the political and constitutional framework and instead resorted to expelling our officials and destroying EPRDF,” Wondimu said.

‘Mutual brinkmanship and mistrust’

A political analyst based in Addis Ababa, who wished to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the matter, said the dispute between Tigray and the federal government comes at the worst time for Ethiopia, which is already battling to slow the spread of COVID-19 and tackle a potentially devastating desert locust invasion.

“The two sides are locked in a cold war of attrition which could drag the whole country into a mess,” the analyst said. “In such a climate of mutual brinkmanship, mistrust and confusion, this could lead to an armed conflict no side intended to enter into just like what happened 22 years ago with the Ethiopia-Eritrea border war.”

Nebiyu Sehul-Michael, the head of the PP’s office in the Tigray region, ruled out an armed conflict but said the TPLF’s destructive political behaviour needed a proportionate answer from Addis Ababa.

“The federal government’s withholding of budget subsidy is meant to significantly end TPLF’s utter lawlessness and treasonable actions,” Nebiyu said.

“The current freeze of relations was quite late due to the federal government’s open-mindedness and leniency. Legal relations with lower bodies and administration can continue based on the federation, the constitution, as well as proclamations and procedures.”

The region was due to receive federal budget subsidies totalling some $280m for the current fiscal year. It is unclear how much of that funding will be affected by the HoF’s move. The federal government has previously said it would funnel funds through lower-level government bodies in Tigray, bypassing the state legislature and executive, although questions remain of how that will work in practice.

Some said the move to cut budget subsidies will likely cause mutual economic pain.

“Tigray has a big tax base and relatively robust manufacturing base. In addition, an economic siege by the federal government would likely backfire, as it would create solidarity between the people and the government in the face of a perceived threat by the central government,” the analyst said.

Already, Tigray region officials have publicly indicated they will retaliate by withholding tax revenues collected in their region from the federal government.

National dialogue, a way out of the crisis?

With both sides seemingly standing their ground, many in Ethiopia have called on for the reactivation of national dialogue to break the political deadlock.

Wondimu, while welcoming such an initiative, said it would not to be all-encompassing, and not just between the TPLF and PP.

“We’re still open for a comprehensive dialogue, illustrated in our call under the federalist forces banner,” said Wondimu.

Similarly, Nebiyu agreed that national dialogue should happen, but accused the TPLF of spoiling the groundwork needed for it to happen.

“Discussions and other peaceful means are of top-shelf importance to resolve any contested issues. But this isn’t easy in a political landscape that was spoiled by the 27-year destructive rule of the TPLF,” he said.

Observers, meanwhile, said while both sides – in principle – may accept entering a national dialogue, the terms they might set could torpedo it right from the start.

“TPLF wants a comprehensive dialogue with other stakeholders in it, as bilateral dialogue with PP would automatically make TPLF a minority stakeholder,” the analyst said.

“PP could see a national dialogue as a time-buying strategy to win an election against a disorganized and repressed opposition possibly to be held by mid-2021.”