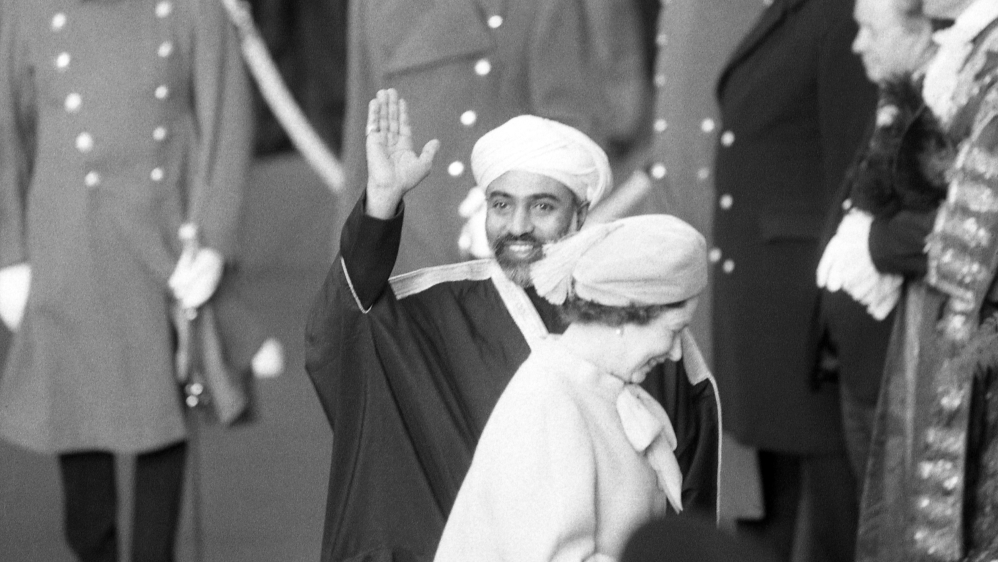

Oman’s Sultan Qaboos, a negotiator in a volatile region

Qaboos was a direct descendant of the founder of the Al Bu Said dynasty and he ruled the Gulf state since 1970.

Oman’s Sultan Qaboos bin Said Al Said died on Friday after half a century as the country’s ruler.

The late sultan was born on November 18, 1940, in Salalah, the capital of Oman’s southern province of Dhofar.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsQatar emir condemns ‘genocide’ in Gaza, urges ceasefire at GCC summit

‘Enduring commitment’: Key takeaways from US-GCC joint statement

Analysis: Efforts to end Assad isolation gather speed after quake

Qaboos is a direct descendant of the founder of the Al Bu Said dynasty, which created the sultanate in the 1600s after expelling the Portuguese from Muscat, now Oman’s capital.

The late sultan was educated in India and at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst.

After completing his military training with the British army in Germany, he studied local government and embarked on a global cultural tour. He returned to Oman in 1964, and spent most of his time thereafter studying Islamic law and Omani history.

When Sultan Qaboos seized power from his father in a bloodless coup in 1970, Oman was an isolated and impoverished state.

Throughout Sultan Qaboos’s five-decade rule, he was credited with using Oman’s oil wealth to transform the sparsely populated Gulf nation into a rich country with a vibrant tourism industry and high standards of living.

“Sultan Qaboos will first and foremost be remembered for initiating the ‘Omani Renaissance’, undertaking social, economic, educational and cultural reforms as well as opening Oman up to the world,” Jeffrey Lefebvre, associate professor of political science at the University of Connecticut, told Al Jazeera.

“In a conservative society, he also took the lead in promoting women to positions of influence in the government [like] the Omani ambassador to the United States, and ensuring representation in popularly elected legislative councils,” Lefebvre added.

Due to a murky succession process, the identity of the next sultan was expected to be not be known for days. But just hours after the announcement of Qaboos’s death, his cousin Haitham bin Tariq Al Said was chosen as his successor.

When Sultan Qaboos came to power, he not only named himself the country’s ruler but also appointed himself as prime minister, defence minister, finance minister, foreign affairs minister and commander of the armed forces.

Sultan Qaboos was the only child born to the former Sultan Said bin Taimur and Princess Mazoon al-Mashani. He married his cousin in 1976, but the marriage did not last and the couple soon got divorced. The sultan never remarried or had any children.

According to Oman’s Basic Law, promulgated by Sultan Qaboos in 1996, “a successor must come from the royal family and be chosen by a family council within three days of the sultan’s death”.

Under this provision, if the process fails to choose a successor, then a sealed letter written by Sultan Qaboos will be opened in which he lists his preferred successors.

“I have already written down two names, in descending order, and put them in sealed envelopes in two different regions,” Sultan Qaboos told Foreign Affairs magazine in a 1997 interview.

In addition to his domestic policy achievements, Sultan Qaboos has also been credited with transforming Oman into a regional player capable of bridging diplomatic divides, as seen in its role as mediator in nuclear talks between Iran and the United States in recent years.

Throughout 2012 and 2013, Sultan Qaboos mediated secret talks between US and Iranian officials. These culminated in the interim nuclear deal of November 2013, reached in Geneva between Iran and the so-called “P5+1” powers, which comprises the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany.

“In [mediating the talks], Oman continued to serve its unique and traditional role as a diplomatic bridge between the West and the GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council] on one side, and the Islamic Republic [of Iran] on the other,” said Giorgio Cafiero, the co-founder of the think tank Gulf State Analytics.

Cafiero told Al Jazeera that Oman’s unique religious identity – the majority of the population are Ibadi Muslims, who are neither Sunni nor Shia – furthers the country’s interest in developing relations with Iran.

“In light of the Saudi Arabian religious establishment’s intolerant views of Ibadi Muslims, most in Oman believe that maintaining political, economic, social, and religious independence from Riyadh is an important foreign policy priority,” he said. “Oman’s government has viewed closer ties with Iran as a means to achieve this objective.”

Mediation

Under Sultan Qaboos’s leadership, Oman also mediated and oversaw talks between the warring sides of Yemen’s ongoing war. In November 2019, Saudi Arabia and Houthi rebels held indirect, behind-the-scenes talks in a bid to end the devastating five-year war in Yemen.

The rapprochement could pave the way for more high-profile negotiations in the near future, a Houthi official had said.

When fellow GCC nations broke ties with Qatar in 2017, sparking a diplomatic crisis, Oman opted out and avoided the fray instead of following suit with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Egypt – who imposed a land, sea and air blockade on Qatar.

Resistance to Sultan Qaboos’s reign was not immune during the popular Arab uprisings of 2011 when hundreds began protesting at a roundabout in Oman’s Sohar province demanding salary increases and an end to government corruption.

The three-month uprising prompted Sultan Qaboos to reshuffle his government and expand the consultative assembly to ease the unrest.

“The government’s proactive reaction to the people’s demands in 2011 allowed for a much more peaceful uprising in Oman compared to other countries in the Arab world,” said Haribi.

In December 2012, Omanis were allowed to vote in their first municipal elections when 192 were elected from among 1,475 candidates.

“Because of his swift response in allowing for democratic changes, we did not see a repeat of protests and demands from the people. Omanis were appreciative of the efforts put forth in building state institutions post-2011,” Haribi added.

In an unexpected move, Sultan Qaboos extended an invitation to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in 2018. Marking what was the first visit by an Israeli leader to the sultanate in over two decades, Netanyahu’s office said in a statement the visit in October 2018 followed “lengthy contacts between the two countries”.

His office added that it formed part of a policy of “deepening relations with the states of the region”.

A joint statement said the two sides “discussed ways to advance the Middle East peace process” and “a number of issues of mutual interest to achieve peace and stability in the Middle East”.

A day after Netanyahu’s visit, Oman described Israel as a “state” in the Middle East, drawing criticism from Palestinian officials.

It was not long after that an Israeli minister visited Oman to attend an international transport conference, which saw him pitch a railway project that aims to link the Gulf to the Mediterranean via Israel, according to media reports.

|

|

Rights record

However, Sultan Qaboos’s human rights record has been condemned in recent years when scores of activists were convicted of defamation or of using social media networks to insult the sultan.

Others have been convicted of, or are facing trial for, taking part in demonstrations calling for political reform.

Among the biggest challenges Oman’s next ruler will face is that of weaning the sultanate of its dependency on oil revenues, which account for as much as 75 percent of the government budget.

“The main focus right now is to continue building human capital through education, civil society and the building of state institutions,” said Haribi.

“It’s not panic time yet. While we’re running out of natural resources, we have to wait and see how the coming few years in the post-Sultan Qaboos era will look like for everyday Omanis,” Haribi added.

Despite Oman’s presence in the media throughout 2018, Sultan Qaboos spent much of the past year out of sight.

In early December, he was taken to Belgium for a medical checkup, according to a royal court statement.