Adel Kamel: Egyptian classic rediscovered in English

The 1941 Malim the Great translated into English in April reignites the renowned writer’s work for a new generation.

In the early 1940s, two young Egyptian writers – one born in 1911 and the other in 1916 – both entered their novels into an Arabic Language Academy competition. Both Naguib Mahfouz and Adel Kamel already had literary standing; both had published pharaonic-themed, philosophical novels.

But in 1942, the committee rejected both Mahfouz’s social-realist The Mirage and Kamel’s satirical Malim the Great. Both novels used language in fresh ways and were critical of Egyptian society.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsKing Charles unveils royal portrait

Cannes film festival hopes for ‘no controversies’ as wars, scandals rage

Energy summit seeks to curb cooking habits that kill millions every year

From that moment, the two gifted writers followed very different paths. The elder Mahfouz went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, while the younger, Kamel, gave up writing for reasons unknown. Still, they remained close friends.

In 1993, a year after Kamel moved to Houston, Texas, to be with his daughters, Mahfouz wrote a tribute: “Adel Kamel, The Harafish, and Literature.” This now appears as a foreword to the English translation of Kamel’s great satiric novel Malim the Great, which appeared in April under a different title in the hopes of appealing to a new audience: The Magnificent Conman of Cairo.

It was Adel Kamel who invited Mahfouz to join the “Harafish”, a group of some of Egypt’s most prominent writers, poets and cinematographers. Mahfouz said they called the cafe where they met in the early years the “Vicious Circle” because they talked endlessly about their frustrations with the country.

All of them were at “the beginning of their literary lives”, Mahfouz wrote in his essay, translated by Waleed Almusharraf.

“Adel Kamel was at the vanguard: brilliant and doing exceptional work,” he said.

|

|

Doubts on art

Kamel published several plays and two novels in the late 1930s and early ’40s. “But, beginning in 1945, he began to have doubts,” Mahfouz wrote. “He doubted the role of literature and the point of art as a whole.”

Although Kamel was alive when Mahfouz published this essay, he made no public response.

Kamel immersed himself in his work as a lawyer, married an Armenian Catholic, and had three daughters who attended French schools and later moved to the United States. Before he joined them in Houston in the early ’90s, Kamel continued to spend a great deal of time with the Harafish. “His literary friends were paramount in his life,” his daughter Mona Farid told Al Jazeera over the phone.

Farid said she did not know why her father stopped writing; that Mahfouz would probably know better. In his 1993 essay, Mahfouz wrote: “Our guess, and it was a guess, was that he did not get the recognition he deserved and that he was terrified of wasting his life.”

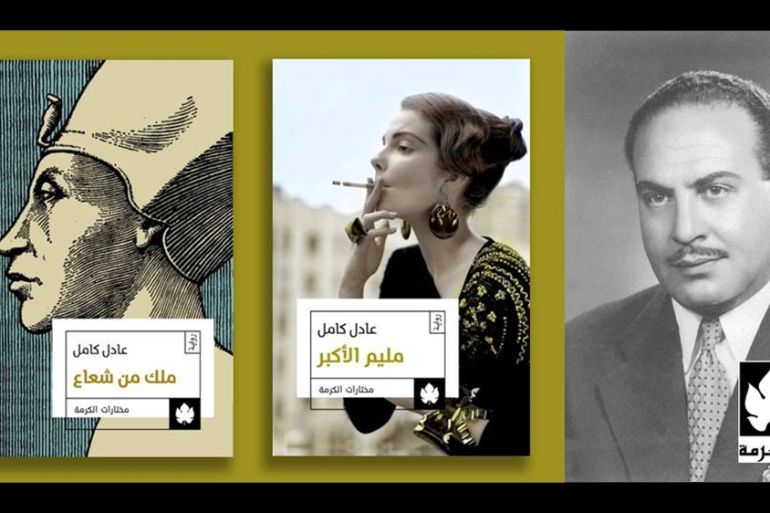

Yet even though he stopped publishing, Kamel’s novels were never completely forgotten – neither his first novel Malek men Shoaa (King of a Ray of Light) nor his satirical Malim the Great, both of which were reissued in Arabic by Al-Karma Publishers in 2014.

Al-Karma launched in 2013 and one of its core undertakings was “Al-Karma Selects”, a project to reintroduce modern Egyptian classics. The firm was looking for books that were “long out of print, a rarity to find – but still not in the public domain,” publisher Seif Salmawy said in an email.

“Important and amazing novels, autobiographies and non-fiction titles by sometimes-obscure authors who perhaps wrote one or two brilliant books and then vanished for various reasons.”

Salmawy said he considers Malim the Great, “one of the most important works of fiction to come out of Egypt in the past century”.

“It had long been out of print and many people had heard of it, but very few had actually read it,” he said.

Nihilist spirit

Translator Waleed Almusharraf had just moved from Cairo to Illinois when he heard about the novel from a friend. The more he read, he said, the more he recognised his own, contemporary Cairo in the book.

“Its humour, the seriousness and helplessness of its activists, the sincerity and pretentiousness of its artists, the miscommunication between its classes, the crowds, the harshness, the orientalism, everything,” Almusharraf told Al Jazeera.

|

|

He added: “I started translating it before I was done reading the novel.”

The novel follows two protagonists from different social classes whose lives converge. The first is Malim – the impoverished son of a conman who wants to make an honest living – and the second Khaled, the drifter-idealist son of Ahmed Pasha.

Egyptian novelist Nael Eltoukhy, who wrote about the book when it was republished in 2014, said Kamel’s novel fits well into the contemporary literary landscape.

“Maybe because of its darkness or of the nihilist spirit hovering in it, I could see groups of hipsters gathering every day in the same place to talk about arts and literature. I could see features of our contemporary world in this novel.”

Kamel continued to meet with his Harafish friends until he moved to Houston, where he lived the last 13 years of his life, passing away in 2005. In those final years, his daughter Mona Farid said he missed his friends and he “read all the time”.

For the most part, Kamel kept his literary life separate from family. “We talked mostly about his spiritual convictions, not literature,” Farid said.

Although her father came from a conservative Coptic background, and his daughters were raised Catholic, “he had a more encompassing view than the traditional religions. He also read about Buddhism, about Hinduism. He opened my horizons and I think he’s the one who made me think, much more, out of the religious box.”

“Maybe literature or art didn’t define his happiness,” Farid said, “because he went beyond.”

In any case, Kamel’s daughters were pleased to see one of his novels arrive in English translation. During exchanged emails about the forthcoming English edition, one wrote: “Akhiran. At last.”