Russia and Turkey: Partners or opponents in Syria?

Erdogan and Putin are holding talks in Sochi, with Ankara’s offensive in northeast Syria high on the agenda.

Sanliurfa, Turkey – Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has arrived in the Black Sea town of Sochi for highly-anticipated talks with his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, hours before a US-brokered ceasefire was set to expire in northeast Syria.

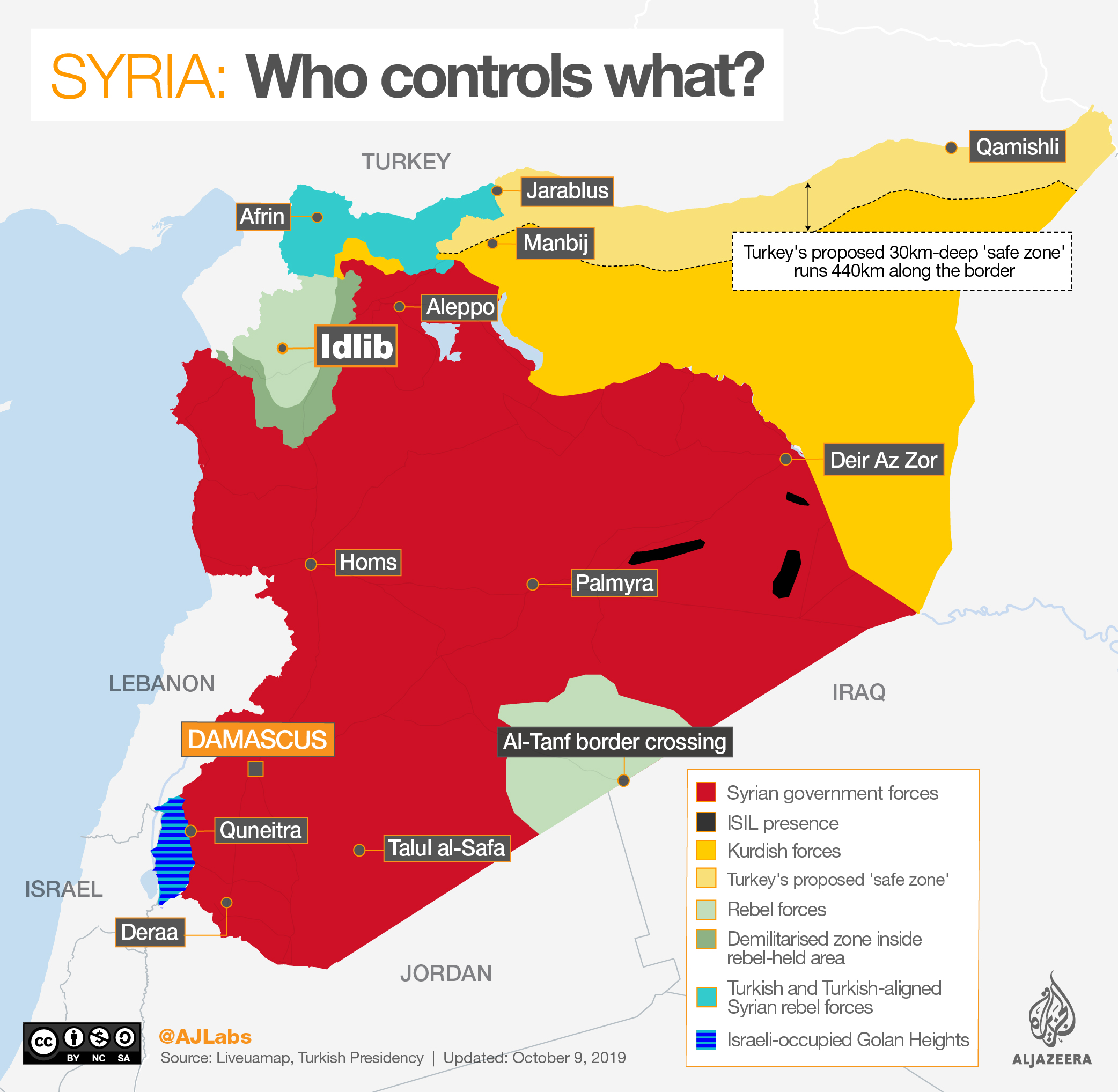

The two leaders were expected on Tuesday to discuss the situation in northeast Syria, where Turkey wants to create a “safe zone” cleared of Kurdish-led fighters now allied to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsTurkey, Russia reach deal for YPG move out of Syria border area

‘We’ve been neutral for years’: Dilemma of Syrian Kurds in Turkey

Russia is al-Assad’s main military backer, alongside Iran.

“The expected outcome of the Erdogan-Putin meeting is an oral agreement to limit the Turkish offensive against the Kurds in Syria,” said Vladimir Sotnikov, a senior research associate at the Russian Academy of Sciences.

“They also want to prevent direct clashes between the Syrian government troops and Turkish forces.”

Ankara and Moscow for years were rivals in the Syrian conflict, providing support to different sides in the war.

Their relationship reached its lowest point in November 2015 when Turkey downed a Russian fighter jet near its border with Syria, before improving after the failed July 2016 coup attempt in Turkey.

In early 2017, the rapprochement eventually led to the launching of talks on Syria via the Astana diplomatic process, which was also joined by Iran.

Wadih el-Hayek, Middle East correspondent for Russian opposition paper Novaya Gazeta, underlined how Moscow-Ankara ties have been on a rollercoaster since the start of Syria’s war in 2011.

“On one end of the spectrum, it reached the point to where Turkey shot down a Russian warplane,” he said.

“On the other, there has been a mutual understanding, and even direct coordination, regarding Turkey’s operation in northeast Syria.”

On October 9, Turkey and allied Syrian rebels launched a long-threatened offensive to drive the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) 30km (19 miles) back from its borders with Syria.

Ankara views the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), which spearheads the SDF, as a “terrorist group” linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a banned group that has waged a decades-long armed campaign for autonomy within Turkish borders.

After more than a week of fighting, Turkey on Thursday paused its operation for five days at Washington’s intervention. The truce – meant to allow the Kurdish forces to withdraw – is due to expire at 19:00 GMT on Tuesday.

The YPG-led SDF was Washington’s main ally in the fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL, or ISIS) in Syria.

But after US President Donald Trump earlier this month announced his decision to withdraw his country’s forces from northeast Syria, thus paving the way for the Turkish assault, the SDF turned to al-Assad.

Last week, al-Assad’s forces entered the strategic city of Manbij for the first time since 2012, under a deal with the SDF aimed to fend off a Turkish assault.

Since then, Russian soldiers have been patrolling the front lines between Syrian and Turkish troops in Manbij, which lies on the M4 highway, a major commercial route. The city is part of the “safe-zone” Turkey wants to create in the border area.

As the end of the five-day truce approached, Coskun Basbug, a retired Turkish intelligence colonel, said he expected the talks between Erdogan and Putin to centre on Manbij as well as Kobane, a town in Syria’s east held by Kurdish forces.

“It is very likely that Turkey will make an offer to Russia to clear the elements of terrorism,” Basbug said, referring to the YPG. “Russia has military and economic cooperation with Turkey, and will not want to waste this opportunity.”

Chechen fighters

El-Hayek offered a different perspective on the talks.

He said the Turkey-Syria border is a “secondary issue” for Russia and that Moscow’s “priority is to ensure the security of its soldiers on the ground from clashing with Chechen armed rebel fighters”.

Thousands of fighters from Chechnya and North Caucasia have headed to Syria to fight with ISIL since 2012, according to el-Hayek. He said these fighters are now located in Idlib, the Syrian rebels’ last major bastion. The northwestern province has been the target of a Russian-backed Syrian government offensive since April.

|

|

The Sochi meeting, el-Hayek said, would present a “quid pro quo” offer – “the neutralisation of these Chechen rebels in return for Russia turning a blind eye to Turkey’s presence in northeast Syria”.

“If these fighters make it back to Russia they’ll have military experience and the potential to create violent instability,” he said, adding: “Russia is willing to ignore its alliance with Syria and Turkey’s cooperation with opposition groups in order to work with Ankara to neutralise these fighters.”

Future presence

Another point up for discussion will be Turkey’s presence in Syria.

El-Hayek said Russia’s official stance was to maintain the territorial integrity of Syria.

“Moscow won’t allow Turkey to remain in Syria forever,” he said. “It will discuss the gradual withdrawal of Turkish troops from the northeast so that Syrian government forces and their allies of Iranian, Lebanese and Iraqi militias will replace them.”

Yet el-Hayek played down the prospects of a clash between Moscow and Ankara.

“At the end of the day, the common interests of these two states stand much larger than being limited to where they stand regarding the Syrian conflict,” he said.

The political positions and interests of states must be differentiated, he explained.

“Turkey signed an arms deal with Russia,” he said, referring to Ankara purchasing the powerful Russian anti-aircraft system, the S-400, despite opposition from fellow NATO states.

“When it is in Russia’s interests to sell weapons to Turkey, then the issue of Syria becomes secondary.”

However, there remains a future possibility that Russia may reach out to the Turkey-backed Syrian rebel groups for political talks.

“Russia doesn’t consider the Free Syrian Army (FSA) as terrorists, like it does with ISIL and al-Qaeda’s affiliate,” el-Hayek said. “There’s a chance that Russia will attempt to reach some sort of agreement with the more moderate elements of the FSA, who could be pressured into doing so by Turkey.”