After 23 years of wrongful imprisonment, Kashmiri men return home

Muslim men from the disputed region released after court acquits them of charges related to a 1996 blast in Rajasthan.

Srinagar, Indian-administered Kashmir – “We are innocent,” wrote Ali Muhammad Bhat in his diary in September 2014 when he was among six men – five of them Kashmiris – awarded life sentences by a court in western India‘s Rajasthan state.

“They had no witnesses against us. Police also said in court that these Kashmiris are innocent,” he wrote, referring to the May 22, 1996 bomb blast in Rajasthan’s Samleti village, in which 14 people were killed.

Police accused a now-defunct rebel outfit, the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, for the blast, linking the six men to the group.

After 23 years of imprisonment in the case without any bail or parole, the Rajasthan High Court on July 23 declared them innocent and ordered their release.

However, the sixth accused, Javed Khan who is also from Indian-administered Kashmir, remains in jail, facing trial over another bomb blast in the Indian capital, New Delhi, which took place on May 21, a day before Samleti. The five others were acquitted in the New Delhi case seven years ago.

Bhat was 24 when he was arrested. Today, he is 47. The first thing he did after his release was to visit the graves of his parents, who died during his long incarceration.

“I cried my heart out. I screamed, shouted, wanted to tell them I have come. I thought they might answer back,” he said.

Ali Mohammad Bhat, who was acquitted of terrorism charges after spending 23 years in jail, breaks down at his father grave #Kashmir pic.twitter.com/CIjoJi7ODS

— Azaan Javaid (@AzaanJavaid) July 25, 2019

On Wednesday, Bhat returned to his family in Srinagar’s Hassanabad locality he had left in 1996 to find unfamiliar faces and a changed city.

“I do not know anyone here,” he said. “When someone comes to meet, I greet them but I don’t know who they are or what their names are.”

When the phone rings and his brother hands it to him, Bhat talks but is unsure how to cut the call short. He has refused to sleep on a soft mattress. “I couldn’t sleep on it. I have a habit of sleeping on the hard cement floor,” he said.

![Bhat's brother shows his picture of 1996 on phone the year when he was arrested. [Rifat Fareed/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/55864ad23e4e446ba0c4cc64c70a2d31_18.jpeg)

The lost 23 years

Towards the end of May in 1996, when prospects of Bhat’s marriage were being discussed at his home in Srinagar, policemen in plainclothes took him away from his rented room in Nepal’s capital Kathmandu, where he sold Kashmiri carpets.

Bhat – along with Abdul Goni, 57; Mirza Nisar Hussain, 39; and Latif Ahmed Waza, 42 from Indian-administered Kashmir – and Rayees Beg from Agra city in Uttar Pradesh state was charged with plotting the blasts in New Delhi and Rajasthan, killing 28 people.

Except Goni, who was arrested in 1997, all the men were arrested in 1996.

“Earlier, when I would hear of Muslims being arrested in terrorism cases, I would believe they might have done it, until I was arrested. I now understand what is done in such cases,” Bhat said.

Bhat, Waza and Hussain live in Srinagar, a short distance from each other.

“All these years in jail when I thought of home, I remembered only those faces I had left behind,” Bhat said as he is surrounded by neighbours and relatives.

As his sister introduces the guests, he remembers few faces.

Bhat said the most painful part of his life in jail was receiving a letter in 2000 that informed him of his mother’s death. “I felt a mountain had collapsed over me. I could not mourn, I froze,” he said.

On her death bed, his mother screamed his name for the last time, said his younger brother, Aijaz Ahmad Bhat. “She lost her mental balance while waiting for him.”

Bhat says he is not able to come to terms with everything that has happened.

“I don’t know how to face my home. I don’t know where to find my parents who died with an incomplete dream of seeing me free.”

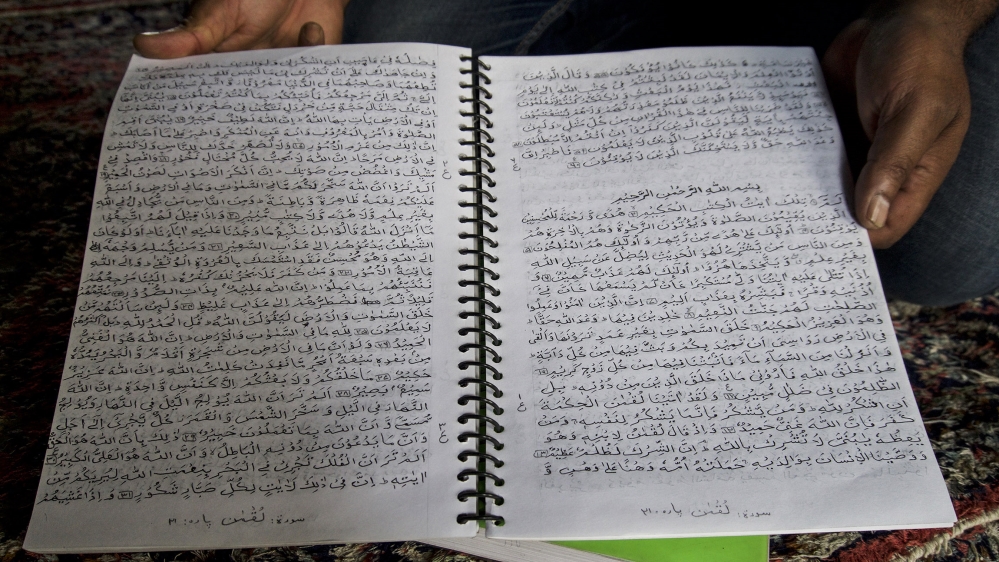

In his jail diary, Bhat wrote about his parents, of memories at home, and the behaviour of other inmates and prosecutors. He also made two copies of the Quran in his own handwriting.

‘My heart is like a graveyard’

Mirza Nisar Hussain was 17 when he was arrested. Back in his home in Fateh Kadal, an old Srinagar neighbourhood, he said he smiled for the first time in 23 years.

“I was very young to understand what had happened,” he said. “I grew up in jail. My first shave was in jail.”

Hussain said he spent his teens and youthful years confined to a 10 by 10 feet (three metre by three metre) cell. “For me, coming to terms with the outside world is going to take forever,” he said.

Hussain’s elder brother was also arrested in the same case, but was acquitted and released in 2010 after 14 years of imprisonment.

Having spent most of his term in jails outside Kashmir, Hussain struggles to speak in his native tongue.

The most painful time, he said, was when he was not allowed to shower or change his clothes for three months.

“We went through the worst kind of torture in the initial days. They deprived us of a bath for three months. We had lice in our hair and even eyebrows,” he said.

“When we finally showered after three months, I told the barber to shave my head, beard and the eyebrows. My heart is like a graveyard now. It’s difficult to tell what was done to us all these years.”

The third man who was acquitted, Abdul Goni, is a resident of Bhaderwah village in Jammu. He reached home on Saturday to a warm welcome by his family and the villagers.

“I kept on pleading that I am a teacher and know nothing about the blasts, but no one listened,” he said.

“There are many like us languishing in jails. Who will give them justice? Who will return our time, our parents and every second of life we lost?” said Goni, who lost his mother when he was in jail.

‘Have you slept, my son?’

Waza’s family members celebrated when he returned home. Candies were showered on him and multiple cuisines were prepared.

Waza was 19 when he was arrested in Nepal where he also sold Kashmiri handicraft. His father died during his time in prison as his mother Noor Jahan waited for his release.

“We had had no celebrations all these years,” said Jahan, who kept her son’s picture hung on her bedroom’s wall.

“Every night when I would go to sleep, I would touch and kiss it, and ask him: ‘Have you slept my son?'” she said as tears rolled down her face.

“Then I would wonder if I have lost my mental balance. I would ask myself: ‘What am I doing?'”

Waza said he would think of his family in his dark and damp jail cell.

“At night, rats would move on the floor as I would try to sleep. I used to get up and scream the name of my father,” he said.

Waza’s father visited him last in 2005 and died days later.

![Lateef Ahmad Waza, sitting at his home in Fateh Kadal, Srinagar, Indian-administered Kashmir. [Rifat Fareed/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/df67848d401449f7b95c987bc1ab3edd_18.jpeg)

‘Justice delayed is justice denied’

Supreme Court lawyer Kamini Jaiswal, who had been fighting their cases since 1996, told Al Jazeera it had been a “mentally exhausting, completely frustrating and exasperating” 23 years.

“For a long time, these people just kept on rotting in jails,” she said.

“What the family had to go through is criminal. They must have lost hope. Ultimately, justice delayed is justice denied,” she said.

While rights activists have criticised successive governments for implicating Muslims in false cases, a recent move by the Indian parliament has stoked fears among the community.

On July 24, legislators passed the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment Bill 2019, which seeks to give the government the power to designate any individual a “terrorist”, if they are found committing, preparing for, promoting or involved in an “act of terror”.

Jaiswal said “no one wants to take responsibility” for such cases involving the Kashmiris.

“Every application for bail is rejected as soon as they hear it’s a Kashmiri. I am sorry, but I think they deal with people from different parts of the country or belonging to different communities in a different way,” she said.

“It is satisfying that they are out. But that it happened after all these years makes me sick.”

While their families are happy at their return, the acquitted men had just one question: now that they have been declared innocent, who will return their 23 lost years?