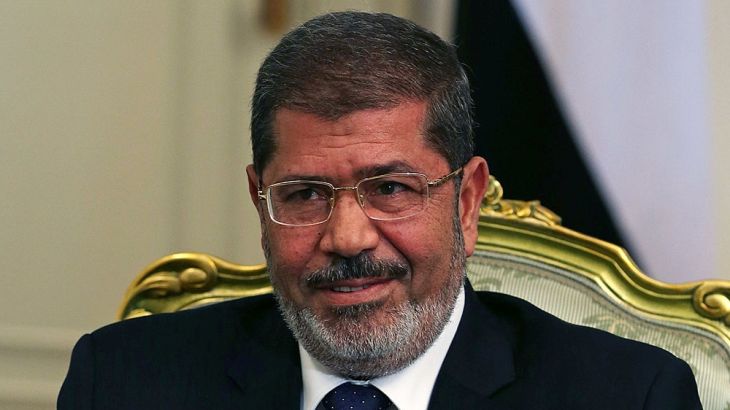

Obituary: Egypt’s first freely elected President Mohamed Morsi

The Muslim Brotherhood leader was the country’s first democratically elected president but was removed in a 2013 coup.

Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president, has died at the age of 67 after a court appearance in Cairo, according to state media.

A member of the Muslim Brotherhood organisation, Morsi came to office in June 2012 after winning 51.7 percent of the vote in a national election, in the aftermath of Egypt’s 2011 revolution.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat challenges do Turkey, Egypt face in restoring ties?

Egypt upholds life sentences for 10 Muslim Brotherhood figures

Egypt and Turkey hold ‘frank’ official talks, first since 2013

However, just one short, roiling year later, Morsi’s time in office was cut short in a military takeover amid massive popular protests against his rule.

He was overthrown on July 3, 2013, in a coup staged by current President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and placed under house arrest before being moved to prison.

In 2015, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison for ordering the arrest and torture of protesters during demonstrations in 2012.

He was also tried in several different cases on charges ranging from leaking intelligence information to collaborating with foreign forces to free prisoners from jail in 2011.

In 2016, he was handed a life sentence for espionage in a case related to the Gulf state of Qatar.

He was on trial for a separate espionage charge when he collapsed in court and later died on June 17, 2019.

Early days with the Muslim Brotherhood

Morsi came of political age among the Muslim Brotherhood generation that demonstrated on university campuses in the 1970s, but he was not part of this protesting group.

“He wasn’t a student leader; he joined the Brotherhood relatively late,” said Abdullah al-Arian, assistant professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar who specialises in modern Islamist movements.

“Instead, he was what you might call a loyal member who deferred to the senior leadership, and because of his loyalty was rewarded through continuous promotion.”

|

|

Later, Morsi was part of the cohort that wedged a space for the Brotherhood under Hosni Mubarak’s government, earning himself a seat in Parliament in 2000.

Under Mubarak, the Brotherhood enjoyed what scholar Mona el-Ghobasy calls “de facto toleration”. But the group occupied an uneasy space in Mubarak’s regime, especially after it won 20 percent of the country’s parliamentary seats in 2005.

Election fraud denied Morsi another term in Parliament and when Morsi spoke out, participating in a demonstration that supported judges who wanted more independence, he was sentenced to jail for seven months.

Political rise

Born in a conservative town on the Nile Delta, Morsi sketched an interesting political figure. He earned a PhD from a university in California, United States, headed the engineering department at one of Egypt’s biggest universities, and his profile on the Brotherhood website boasted a consulting stint with the NASA space programme (perplexingly, Morsi later deniedever having worked there in a local TV interview).

Morsi took strong stances on social practices he viewed as blasphemous.

In 2011, he led a boycott of a major Egyptian mobile phone company because its owner had tweeted cartoon depictions of Minnie Mouse in a face veil.

Four years earlier, he had been tasked with helping author a position paper for the Guidance Council, the Brotherhood’s ruling group.

The final mandates included a ban on women and Coptic Christians from serving as president, as well as the formation of a council of Islamic scholars to advise Parliament on the law. Their role would be extra-constitutional, but non-binding.

Bu by 2012, a newly elected Morsi had refined his stance.

“I will not prevent a woman from being nominated as a candidate for the presidency,” he told a New York Times reporter. “This is not in the Constitution. This is not in the law. But if you want to ask me if I will vote for her or not, that is something else, that is different.”

|

|

‘Man of the people’

The Muslim Brotherhood was navigating tricky political space when Morsi became the country’s first democratically elected president in 2012.

His successful campaign contradicted earlier claims by the Brotherhood that they would not run a presidential candidate.

When Morsi came to office, it was in the aftermath of a revolution, among a highly polarised population that gave him 51.7 percentof the vote.

|

|

According to Wael Haddara, one of Morsi’s campaign advisers, the president appealed to a public desire for a more accessible leader.

“The counternarrative that Morsi wasn’t a popular person, that Egypt needed a more charismatic figure, was not true … For the first four months, Morsi’s popularity [ranking] was in the stratosphere,” Haddara told Al Jazeera.

“He presented to people an accessible figure. A vast majority of Egyptians eking out a living, struggling to make ends meet, looked at Morsi as one of their own,” he added.

When Morsi swore an informal oath in Tahrir Square, he opened his jacket before supporters to show he wasn’t wearing a bulletproof vest. Upon taking office, one of his first decisions was to order the release of 572 prisoners that had been detained after the revolution by the army.

Morsi himself had been jailed during the 2011 uprising, before escaping in a mass prison break among other Brotherhood leaders and members of Hamas and Hezbollah.

One of Morsi's mistakes during his presidency was that he led people to assume that he'd taken the reigns of the state when in fact he hadn't. He was simply put in a position to give people the idea that a real revolution had occurred. The state, meanwhile, was very much in the hands of the same people as it was under Mubarak

Mistakes

Despite the widespread perception of Morsi as a man of the people, Egypt’s new president faced stiff political opposition and the hard ridges of a divisive post-revolutionary society.

The president was officially sworn into office two weeks after the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) issued an interim declaration, awarding itself all legislative powers and effectively stripping Morsi’s office of authority. The lower house of Parliament, with its Brotherhood majority, had also been dissolved by Egypt’s Mubarak-era Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC).

“One of Morsi’s mistakes during his presidency was that he led people to assume that he’d taken the reigns of the state when in fact he hadn’t. He was simply put in a position to give people the idea that a real revolution had occurred. The state, meanwhile, was very much in the hands of the same people as it was under Mubarak,” said al-Arian.

As Morsi navigated the political potholes of office, opposition politicians pelted him with criticism for what they saw as dictatorial manoeuvres to wrangle back power. In August 2012, Morsi nullified the SCAF declaration and put forth one of his own, allotting himself the power to pass laws and select a new constitution-drafting committee.

Morsi promised to forgo these expansive powers after the election of a new parliament, yet some still saw his decision as a political overstep.

The move was coupled with the forced retirement of Mubarak-era senior generals, political strongholds who had been entrenched in Egypt’s elite circles for decades.

“Morsi often talked about the idea that an individual may have an opportunity for change that will come along three times or even four times. You can blow your opportunity and another will come,” said Haddara. “Nations aren’t like that. You may have an opportunity once every generation, and January 25 represented that.”

Though Morsi was mindful of the sacrifices made during the January 2011 uprising before him, his efforts to push the country ahead were often stalled or criticised.

In November 2012, after garnering international goodwill for helping broker a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, Morsi issued a decree that further broadened his executive powers and granted protection to the committee drafting a new constitution. The move was widely seen as a way to shield the committee from challenges by Mubarak-era judges.

|

|

“If we did not actually have a constitution, then we would be back to square zero,” said Haddara of the manoeuvre. “Much in the same way that the parliament was dissolved by an organ of the ‘ancien regime’, the fear here was that this would mean harking back to greater instability for the country.”

Yet, some outraged critics saw the move as unacceptable. By the time he revoked his decision 10 days later, Brotherhood supporters and leftists had already clashed outside the presidential palace in deadly street fights.

“When it comes to politics, it’s all about how you package your decisions as a leader. Morsi could have done a better job at presenting what he was doing. He was indeed trying to fulfil the demands of the revolutionaries, but because he had engendered so much ill-will – especially after a shameless media campaign that constructed an exaggerated image of him – when he finally did something, everyone was outraged,” said al-Arian.

Riddled with walk-outs by liberal, leftist and Mubarak-era politicians, the constitutional drafting process had been portrayed by some critics as an exclusionary endeavour, void of the potential for dialogue. Yet, in a televised address after November’s legal changes, one of Morsi’s advisers, Gehad al-Haddad, claimed that the “door is still open”.

Though the president had frequently been criticised for refusing to step outside his trust circle, supporters point to his efforts to be inclusive. In December 2012, Morsi’s appointments to the upper house of Parliament had been 75 percent non-Islamist affiliated.

And according to Haddara, throughout Morsi’s time in office, his popularity never dipped below 60 to 55 percent.

|

|

Yet Morsi’s presidency was complicated by the heavy economic frustration weighing on Egypt’s population. The currency’s value was faltering, and unemployment had ballooned to 13 percent – all the while, Morsi was failing to secure a loan with the IMF.

Haddara notes that, when Morsi came to office, foreign currency reserves had been sapped by SCAF. Even so, gross domestic product grew from 1.8 percent to 2.2 percent (against market prices) between 2011 and 2012, and Haddara claims that tourism registered a return to pre-2011 levels.

A mediascape saturated with bias, in which local TV stations were quick to criticise Morsi’s policies, labelled Brotherhood supporters as “terrorists” and cheered on air after the president was arrested, did not help the executive office’s image.

“There were real issues that cannot be minimised … On the other hand, the media exaggerated some of the challenges that were being depicted,” said Haddara, noting the “magical disappearance” of certain social and economic grievances once Abdel Fattah el-Sisi came to power.

Others complained that Morsi’s efforts had bumped against the bureaucracies and entanglements erected by a deep state. Morsi’s minister of supply said Egypt’s deep state was activelyworking against him, noting that gas stations raised their prices and did not implement a smart card system designed by Morsi that would have tracked fuel shipments.

|

|

“I don’t think that the Brotherhood ever maintained political power; instead, there was an illusion of power that they played along with,” al-Arian said.

Lambasted for doing too much in the political arena, but too little for gas prices and food security, Morsi attempted to pacify the population in one of his last speeches in June 2013.

“I have made mistakes,” he admitted, but the crowds gathered at Tahrir Square by then did not care for his conciliatory tone.

‘Premature death likely’

By this point, protests both in favour of and against Morsi’s removal were rolling across the country. Days later, Morsi was issued an ultimatum by the military to either step down or face a military coup. He was overthrown in the July 2013 coup, and placed under house arrest before being moved to prison.

Within months he went on trial, along with other senior Brotherhood figures, in a case related to the killing of protesters in clashes outside the presidential palace in 2012.

In April 2015, he was sentenced to 20 years on charges of ordering the arrest and torture of protesters in the case, but was acquitted of murder charges.

In September 2016, Morsi was handed a life sentence on charges of passing intelligence to Qatar. And in December 2017, he was also sentenced to three years on charges of insulting the judiciary.

Amnesty International has described Egypt’s judicial system as “horrendously broken” and called death sentences handed out to Morsi and other members of the Muslim Brotherhood in previous trials a “vengeful march to the gallows”.

In a report released by the Detention Review Panel (DRP) in March 2018, a panel of British MPs and lawyers warned that Morsi’s conditions of imprisonment had left him facing a “premature death”.

The panel, which was commissioned by Morsi’s family, said the former leader was “receiving inadequate medical care, particularly inadequate management of his diabetes, and inadequate management of his liver disease”.

|

|

“The consequence of this inadequate care is likely to be rapid deterioration of his long-term conditions, which is likely to lead to premature death,” it said.

The panel said the conditions of his detention could meet the threshold for torture in Egyptian and international law. It added that el-Sisi “could, in principle, be responsible for the crime of torture”.

He was held at the infamous Tora Prison, also known as Scorpion Prison, where the DRP said he had been held in solitary confinement for about three years.

“[The prison] was designed so that those who go in don’t come out again unless dead,” said Major General Ibrahim Abd al-Ghaffar, a former Scorpion warden during a TV interview in 2012.

“It was designed for political prisoners.”