Egypt’s 2018 presidential ‘election’: What you need to know

Egyptians abroad prepare to vote beginning on March 16 in Egypt’s fourth contested presidential polls.

Experts have already dubbed Egypt‘s presidential election this month as a “sham”, and predict that President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi will undoubtedly win a second presidential term after eliminating any real political opposition.

Widespread condemnation over the decline of the economy and Sisi’s internal policies led many to call for a boycott of this year’s election, which is the fourth contested presidential election in Egypt’s history.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTurkey and Egypt call for ceasefire in Gaza

Turkey’s Erdogan, Egypt’s Sisi meet in Cairo

Turkey’s Erdogan arrives in Egypt for first visit in more than a decade

The economy under Sisi has sputtered posting as high as 35 percent inflation in July 2017. The country’s economy is also under a $12bn IMF bailout. Currently, 28 percent of Egyptians live under the poverty line.

Sisi has promised to cut taxes and reduce bureaucracy in order to boost investment, and pledged to work towards the development of the Sinai Peninsula, a volatile desert region facing an armed rebellion.

Running alongside Sisi is Moussa Mustafa Moussa, chairman of the liberal El-Ghad Party, and a Sisi loyalist.

The 66-year-old has repeatedly endorsed Sisi, and last year formed a campaign called, “Supporters of President el-Sisi’s nomination for a second term”.

In an interview with Al Jazeera, Sahar Aziz, professor at Rutgers Law School in the US, questioned the legitimacy of Moussa as a candidate, saying he could just be a “placeholder”.

Moussa is being mocked by Egyptians, who refer to him as Al-Kombares, which loosely translates to playing the role of an “extra”.

Since coming to power in mid-2013, Sisi’s government imposed a series of punitive decisions described as “unprecedented” by rights organisations such as Human Rights Watch.

Yet, Egyptians prepare to hit the polls in waves – both locally and internationally – to choose a new president.

How it will work

On Friday, March 16, Egyptians living abroad will be able to cast their vote in the 139 polling stations around the world, with the exception of Libya, Yemen and Syria.

According to the World Bank’s latest figures, there are some 10 million Egyptian expats in various countries around the world. Those who are 18 years and above – registered in the election database – are entitled to vote.

As of 2016, the World Bank placed Egypt’s population at 96 million. Of that, 60 million are eligible voters.

In the event that none of the candidates garners more than 50 percent of the votes, a runoff will take place in April.

To be eligible to run for president, a candidate must collect 25,000 signatures from constituents across 15 out of the country’s 27 governorates, with at least 1,000 signatures from each area.

Alternatively, the signatures of 20 parliament members would suffice.

Silencing opposition

Though a handful of potential candidates previously expressed interest in running for presidency, Sisi’s government managed to increasingly restrict public space in Egypt, forcing many who were eligible to run to step back.

Through a series of legal amendments and presidential decrees, Sisi managed to strike out opponents ever since he took office – starting with the banning of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood from participating in political life.

In January, ex-presidential hopeful Sami Anan, was detained by the military just days after announcing his candidacy. He was accused by the military of failing to secure permission from the army to run.

Khaled Ali, a human rights lawyer who ran for president in 2012, also withdrew from the race. He faces a suspended jail term after receiving a three-month prison sentence for allegedly “offending public decency” during a protest.

Ahmed Shafik, the country’s former prime minister and a close aide to deposed President Hosni Mubarak, also backtracked on his plan to run.

|

|

Similarly, army colonel Ahmed Konsowa was sentenced six years in prison after he announced his plans to run for president last year, after he was accused of “stating political opinions contrary to the requirements of military order”.

Mohammed Anwar Sadat, a nephew of the slain Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat, also called off his campaign blaming what he called an environment of fear surrounding the election.

And Abdul Moneim Aboul Fotouh, a leading opposition figure and former presidential candidate, was detained last month over his alleged ties with the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood.

In an exclusive interview with Al Jazeera in February, Fotouh said the upcoming election is a “referendum with guaranteed results”, and encouraged Egyptians to boycott the “absurd” vote.

Experts say that with the current lineup, it is unlikely that Sisi will be replaced in a civilian election.

Aziz, the professor at Rutgers Law School, noted that targeting even former generals “shows the level of desperation and level of aggression” of the Sisi regime.

Will this election bring change?

|

|

The current form of the country’s so-called democratic election is not distinct from the three previous elections.

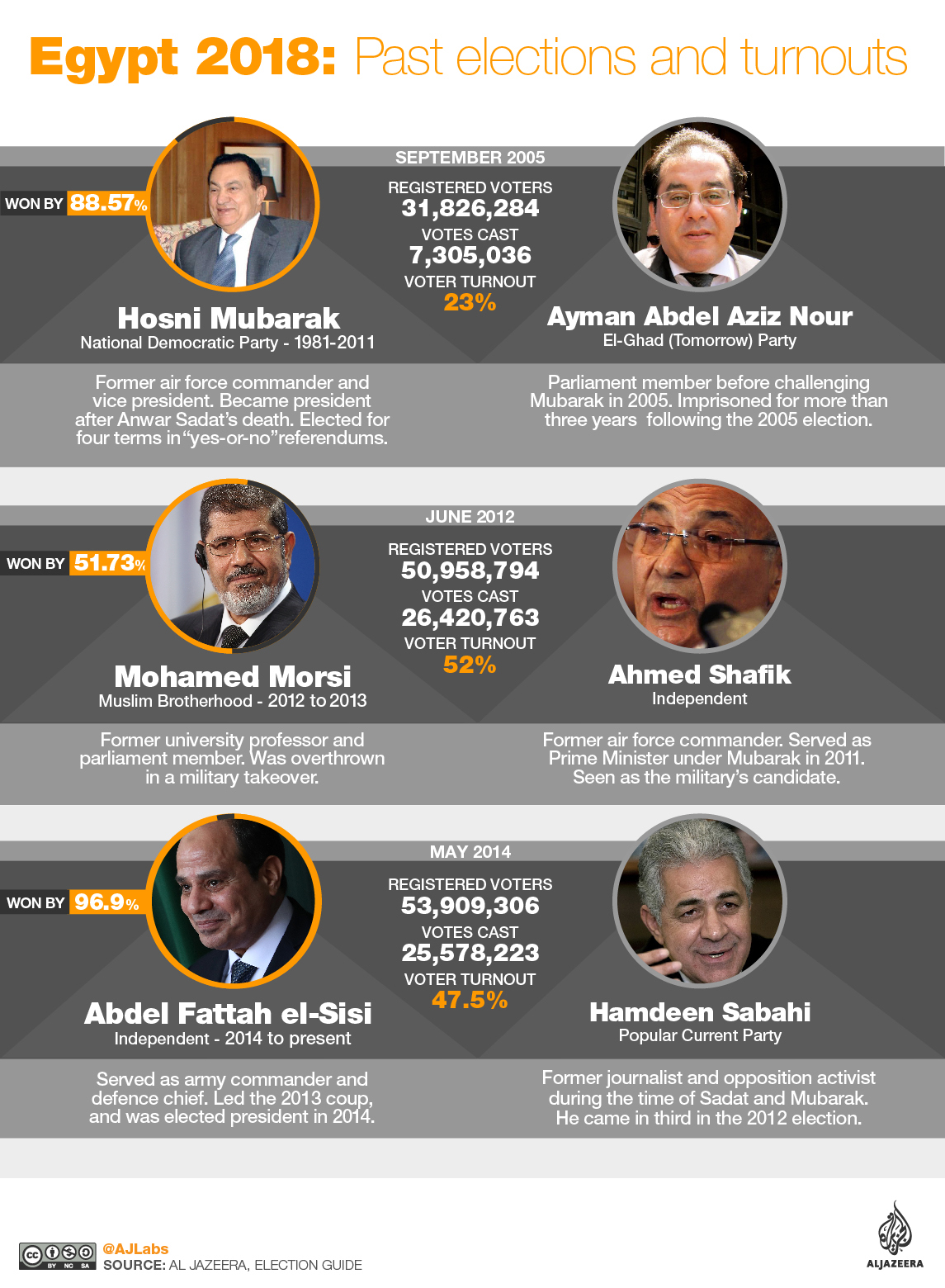

Two of Egypt’s three previous elections, which took place in September 2005 and May 2014, were considered by international political observers as spurious.

Prior to 2005, then-President Hosni Mubarak was elected to four terms in “yes-or-no” referendums. Mubarak served from 1981 until his overthrow in 2011.

In 2012, the term of Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi was short-lived, after the military launched a bloody coup led by Sisi, who back then was an army chief.

The 2012 election was considered as the first ever democratic presidential polls in the country’s history. A total of 13 candidates contested the first round of voting, with four of them engaged in a close race. Morsi emerged as the eventual winner in the runoff, with just over 50 percent of the vote.

Following Morsi’s removal, the Muslim Brotherhood political movement itself was banned in the country.

Meanwhile, a coalition of opposition parties are calling for a boycott of what they termed as an “absurd” poll.

But with no competitive election facing Sisi, it remains unclear how real change in Egypt could come about.