Why there can never be a two-state solution

As Palestinians mark 50 years since the UN ordered Israeli forces to withdraw, experts say lasting peace is impossible.

For the past 50 years, a United Nations Security Council resolution has helped to sustain Israel’s occupation of Palestine, analysts say.

Ghada Karmi, a British-Palestinian author and lecturer at Exeter University’s Institute of Arab and Islamic studies, says the central issue is that Israelis “never intended” to comply with UNSC Resolution 242, adopted on November 22, 1967.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS secretly sent long-range ATACMS weapons to Ukraine

Russia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 791

US top diplomat Blinken calls for ‘level playing field’ for firms in China

“From the steady colonisation of the Palestinian area, you can see that there has been no attempt on the part of Israel to comply with any part of the resolution,” she said.

Resolution 242

Following the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, a resolution called on Israel to give up the territories it occupied in exchange for a lasting peace with its neighbours.

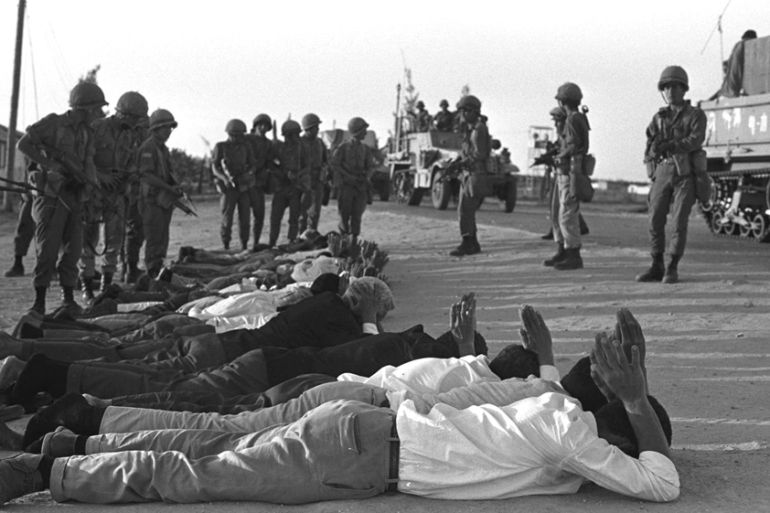

Israel defeated the armies of Egypt, Jordan and Syria, resulting in the Palestinian “Naksa”, or setback, in June 1967.

In that year, Israel expelled some 430,000 Palestinians from their homes. The Naksa was perceived as an extension of the 1948 Nakba, or catastrophe, which accompanied the founding of the state of Israel.

In a matter of six days, Israel seized the remainder of historic Palestine, including the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza, as well as the Syrian Golan Heights and the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula. Later that year, Israel annexed East Jerusalem as well.

Apart from the Sinai Peninsula, all the other territories remain occupied to this day.

Under the sponsorship of the British ambassador to the UN at the time, Resolution 242 aimed to implement a “just and lasting peace in the Middle East” region.

The resolution’s preamble explicitly prohibited the continuation of Israeli control over territory that was acquired by force during the war, citing “the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war and the need to work for a just and lasting peace in which every State in the area can live in security”.

The resolution called on Israel to withdraw its forces from territories it had occupied in the Six-Day War, and urged all parties to acknowledge each other’s territorial sovereignty.

(i) Withdrawal of Israel armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict;(ii) Termination of all claims or states of belligerency and respect for and acknowledgment of the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of every State in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force

However, the resolution was used by Israel to continue its occupation of the territories, as it also called for “achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem” while falling short of addressing the Palestinian people’s right to statehood, analysts note.

As a result, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which at the time was perceived by the international community and by the UN as the representative of the Palestinian people, refused to acknowledge the resolution until two decades later.

The resolution was later used as the basis for Arab-Israeli peace negotiations and the notion of creating a two-state solution along the internationally recognised 1967 borders.

But in the US-based Journal of Palestine Studies, lawyer and Georgetown University professor Noura Erekat wrote that Israel has used Resolution 242 to justify the seizure of Palestinian land.

“When Israel declared its establishment in May 1948, it denied that Arab Palestinians had a similar right to statehood as the Jews because the Arab countries had rejected the Partition Plan,” Erekat wrote, referencing UN Resolution 181.

The final language of Resolution 242 did not correct the failure to realise Palestinian self-determination, referring merely to the “refugee problem”, she added.

“Following the 1967 war, Israel argued that given the sovereign void in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip the territories were neither occupied nor not occupied,” Erekat said, noting that Israel used this argument “to steadily grab Palestinian land without absorbing the Palestinians on the land”.

Though Resolution 242 qualifies “occupied territories” as those areas occupied or acquired during the war, analysts say Israel used the “vagueness” of the language to its benefit.

“[Israel and its allies] are saying there isn’t anything specific – there aren’t any specific territories mentioned – which means, ‘We can have this or that,'” Karmi said.

“This whole vagueness argument is artificial, to throw dust in the eye. The problem with the resolution is that it has never been implemented. That is one of the most serious things about it.”

Sustaining the occupation

Mouin Rabbani, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Institute for Palestine Studies, said the political context of the time was the underlying force behind the resolution’s lack of execution.

“Israel’s victory in 1967 was largely seen as an American victory as much as an Israeli victory,” Rabbani told Al Jazeera. “This was in the height of the cold war.”

The United States’ UN representative at the time played a significant role in trying to steer the resolution in Israel’s favour, he said.

“It [Israel] had absolutely no intention of leaving, and it never came under sufficient political or military pressure whereby the costs of remaining in the occupied territories became higher than benefits of doing so,” he said.

The importance of Resolution 242 actually came much later, after political developments formed the basis of an international consensus for a two-state-solution – a notion that began to emerge among the Palestinian leadership in the 1970s, Rabbani said.

“Today, we always talk about the Palestinian/Israeli conflict – that didn’t really exist at the time,” he said. “It was the Arab/Israeli conflict and the question of Palestine.”

Palestinian dispossession

The fact that Palestinian statehood was not awarded much significance in the resolution is not the outcome of deliberate sidelining; rather, it is due to the political lens in which Palestine was seen at the time.

Despite the fact that Resolution 242 paved the way for negotiations, it is now “completely irrelevant”, Karmi said.

“The basic issue to resolve this conflict is return. This is the basic issue – these people [the Palestinians] are dispossessed,” she said.

But even with a series of brokered peace talks, there has been no real progress towards implementing a two-state solution, with discussions at a stalemate amid the expansion of Jewish settlements.

The soaring settlement project, which is in direct contravention of international law, has brought around 600,000 Israelis into dozens of Jewish settlements throughout the occupied West Bank. Israeli authorities expropriate Palestinian land and carry out home demolitions on a regular basis, most commonly to expand existing settlements, or occasionally to build new ones.

Checkpoints and Israel’s separation wall have further hindered Palestinians’ freedom of movement.

“Israel is totally in control of the Palestinian territories – not just the West Bank, but also Gaza,” Karmi said.

The Gaza Strip, home to about two million people, has been under siege for more than a decade. In 2007, after the election victory of Hamas and the group’s assumption of control over the territory, Israel imposed a strict land, aerial and naval blockade.

“The fact of total Israeli control of 100 percent of Palestine is precisely and fundamentally why you can’t have a two-state solution,” Karmi said.

|

|