How will the battle for Mosul affect Iraq?

Analysis: What happens in Mosul could determine the future direction of the country.

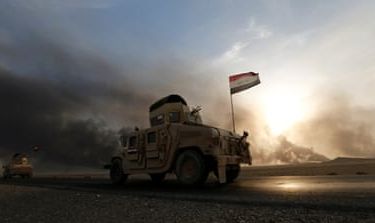

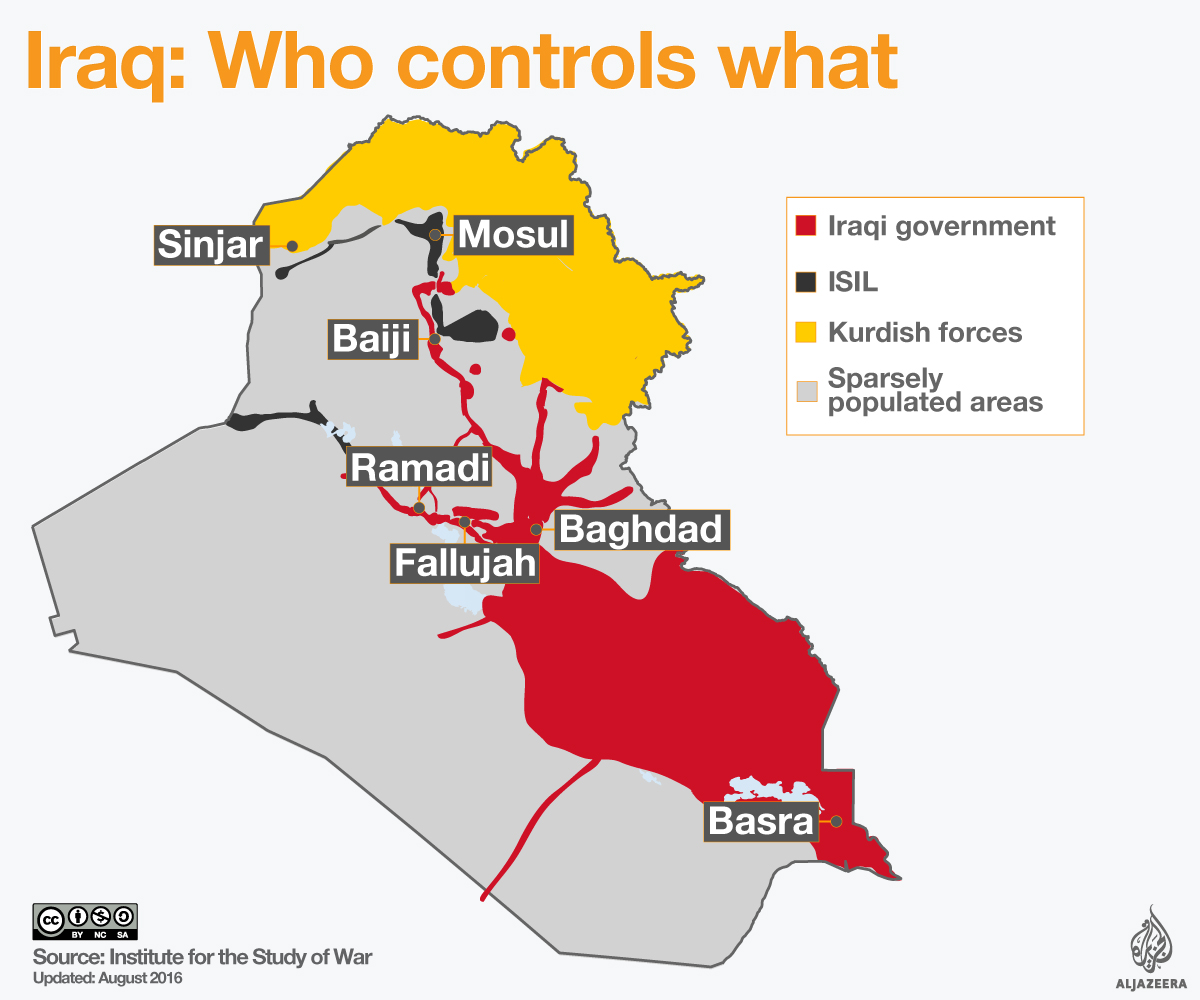

The battle for Mosul is intensifying as Iraqi government forces and Kurdish troops edge closer towards the country’s second-largest city. According to the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) interior ministry, the Iraqi army is only five kilometres from Mosul – and they could be even closer.

Several towns and villages have recently been cleared, including the predominantly Christian towns of Bartellah and Qaraqoush, southeast of Mosul. Fierce battles are raging on multiple fronts.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWestern volunteers join the battle against Myanmar’s military regime

Russia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 813

Photos: ‘Living in fear’ amid relentless battle for eastern DR Congo

But fighters of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS) are hitting back hard. ISIL fighters have slowed down the advancing forces by waging waves of coordinated suicide car-bomb attacks, deploying tens of snipers and relying on a network of trenches and tunnels.

ISIL is also manoeuvring and relying on old tactics seen in previous battlefields in Iraq.

READ MORE: Mosul battle could cause a ‘human catastrophe’

|

Another key question is what is next after the government presumably declares ‘victory’ over ISIL? Many people in Iraq fear that the seeds for other extremist groups are already planted. |

On Saturday, a group of suicide attackers and fighters launched an early-morning raid on a government building and a power plant in the ethnically mixed, Kurdish-dominated city of Kirkuk, which is southeast of Mosul.

The attack killed more than a dozen people. ISIL’s aim was to distract and confuse Iraqi government forces and Kurdish Peshmerga fighters, to open new fronts and to grab international media headlines.

Similar tactics were employed during the battles to retake the cities of Tikrit, Ramadi and Fallujah.

The Iraqi government and Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi appear determined to recapture ISIL’s stronghold of Mosul. Abadi had previously said that ISIL in Iraq would be defeated by the end of 2016.

It could be a matter of time before this plan succeeds, however. ISIL is outnumbered and outgunned, but there are growing fears over the human costs of this campaign.

US-led coalition warplanes have been pounding targets in Mosul for months. They have stated that the targets were ISIL positions, but reports from inside the city suggest that civilians are also being killed.

Mosul has a population of more than two million people. It is not clear how many have left since ISIL captured the city back in June 2014.

|

|

Some residents have fled, but the vast majority remain trapped at the mercy of ISIL, the coalition air strikes, Iraqi army forces, Peshmerga fighters and Shia militias. The stakes for Mosul are high. What happens there could determine the future of Iraq, and the direction in which the country will head.

Another key question is what is next after the government presumably declares “victory” over ISIL? Many people in Iraq fear that the seeds for other extremist groups have already been planted.

A quick flashback to 2003 reminds us that ISIL had its origins in al-Qaeda in Iraq, led by Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Zarqawi galvanised many fighters, transformed the group and introduced new insurgency tactics.

After his death in a US military raid in 2006, the group became known as the Islamic State of Iraq, led by Abu Omar al-Baghdadi. Baghdadi was killed by Iraqi and US forces in 2010, and the group got yet another leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, a former inmate held in a US prison in southern Iraq in 2004 and set free four years later.

He ultimately led the group to fight in Syria’s war in 2012 and formed what is the present-day ISIL. Many Iraqis argue that the main reason that such groups exist is the injustice inflicted on Iraq’s Sunni Arabs since 2003.

ANALYSIS: Can Iraq defeat ISIL without destroying Mosul?

The Iraqi government has a huge responsibility. It needs to end the perceived marginalisation of Sunnis and end arbitrary arrests, torture and humiliation. Some analysts cite the need for a real and effective reconciliation process to create jobs and implement real power-sharing.

The implications for not doing so are dire, not only for Mosul but for the rest of Iraq. There are genuine fears that the post-ISIL generation will be more brutal. Such assumptions are based on the fact that Osama Bin Laden’s al-Qaeda was seen as extreme when it surfaced, but when Zarqawi showed up in Iraq, al-Qaeda’s attacks and tactics seemed less brutal in comparison.

With ISIL, the brutality turned into blatant savagery. Another important factor to watch out for this time is the rising power and the spread of extreme Shia militias fighting ISIL. The Popular Mobilisation Units – Shia paramilitaries funded and armed by Iran – are a growing force in Iraq.

There are more than 40 of these groups operating in the country. Many of them are very powerful in terms of weapons, intelligence and unshaken loyalty to Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei.

Abadi has said that he, as commander in chief, maintains control over these militias. In reality, he does not: According to human rights groups, Sunni politicians and witnesses, these militias have been involved in war crimes, revenge attacks, ethnic cleansing, torture, abuse and executions against members of the Sunni population.

They are accused of changing the demographics in areas that used to be under ISIL’s control in the provinces of Diyala, Salaheldin, Anbar and areas known as the Belt of Baghdad that surround the Iraqi capital. The US military is providing support and air power not only to Iraqi forces, but also to Shia militias involved in alleged war crimes.

The Americans deny it, but this is what happened during the battles of Tikrit, Baji, Ramadi and Fallujah. In a nutshell, all of these factors will only fuel the anger towards the US and the Shia-led government in Baghdad – and that is the best breeding ground for new groups to garner support and find endless recruits in Iraq and beyond.

Omar Al Saleh is a former Al Jazeera correspondent and an analyst on Middle East affairs.