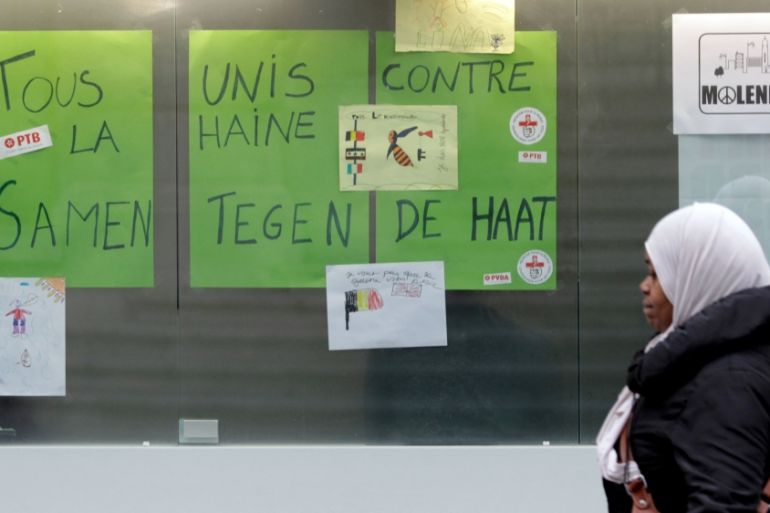

Don’t scapegoat our children, say Molenbeek mothers

Molenbeek women say stigma can help drive youth to ISIL, as government is also criticised for police funding cuts.

Since the Paris attacks, the impoverished neighbourhood of Molenbeek in Brussels has become as infamous as the home base of some of the attackers.

Belgium Interior Minister Jan Jambon has chimed in, promising to “clean up” Molenbeek.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAustin confirms Russians deployed to airbase housing US military in Niger

What’s next as ‘heavy-handed’ US negotiates pullout from Niger?

Putin says ‘radical Islamists’ behind Moscow concert hall attack

But several dozen Molenbeek mothers in a recent open letter to the interior minister argued that sweeping generalisations about their community are unfair and counterproductive.

“We want to remind you we are responsible citizens with rights,” the mothers wrote in the letter published Thursday. They asked Jambon not to make their community “the scapegoat for everything that goes wrong in this country”.

Several suspects in the Paris violence and other recent attacks in Europe are linked to Molenbeek.

Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the alleged planner of the Paris attacks who was killed this week in a police raid in that city, was raised in Molenbeek.

Related: A message from Molenbeek: ‘We are not terrorists’

Jambon said this week that Molenbeek is home to 85 of the 130 people who returned to Belgium after fighting for the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). He told Belgian media that he wants local authorities in Molenbeek to conduct door-to-door checks.

“It is unacceptable that we don’t know who is present on the territory,” he said in an interview in Het Nieuwsblad.

“There are two people registered in some apartments, but 10 who live there.”

The interior minister additionally promised a more holistic approach to Molenbeek that would include a focus on better education, city planning, and equal opportunities for the area’s residents.

The women who penned the letter to Jambon said in interviews that they had previously asked the minister to join them for a meal, which he refused. They hope he will change his mind.

“It would send a very positive sign if he came to Molenbeek,” one woman said in an interview.

The women are organised around Dar al-Amal, or “The House of Hope” in Arabic, a women’s centre that provides educational and cultural activities.

They declined in interviews to give their names, saying that each of them speaks for the group.

Related: France and Belgium carry out counterterrorism raids

Jambon “lays responsibility for the attacks at our door”, one said.

“We would also ask him to choose his words better. He should make sure our children have the same possibilities instead of talking about us like [we are] some different breed.”

Dehumanising language “strip[s] our children of their attachment to the country”, one mother said.

“It’s things like this that make kids go to Syria.”

A community facing challenges

Jef Van Damme, a Flemish Socialist politician representing Molenbeek, calls Molenbeek “a social elevator”.

“Over the last 20 years, 100,000 people came to Molenbeek and about as many left,” Van Damme said.

“Molenbeek is the first point of arrival for many poor people coming to Belgium. The [government] helps them with housing, training and finding a job.

“They work themselves up and leave for other places in Belgium. Then they are replaced by new, poor people, and so the circle starts again.”

He added that the Paris attacks horrified local residents, but it also brought them together.

“There have been many signs in the aftermath of Paris that people feel something must be done.”

“Jambon’s statements were misplaced, but we hope the federal government will eventually work together with us rather than speaking against us,” Van Damme said.

Johan Leman, a priest and professor, heads a multiethnic nonprofit organisation that has been active for more than 30 years in Molenbeek.

“When I heard Jambon say that he wanted to ‘clean up’ Molenbeek … I laughed,” Leman said. “It’s not how things work.”

He said the neighbourhood’s young people are coping with a changed economy. Many manual labour jobs that kept their parents’ generation employed no longer exist, Leman added.

Police funding cuts

Since the Paris attacks, Jambon has promised to beef up police efforts in Brussels.

But Dave Sinardet, a professor of political science at the Free University of Brussels, said the centre-right government’s funding cuts don’t square with this promise.

“There is a contradiction between the government’s law-and-order agenda and its efforts to shrink the state,” Sinardet said.

When Jambon gathered police representatives this week to discuss how officers would deal with a greater workload, the conference didn’t end well: Police unions threatened to go on strike.

“The minister is pulling the wool over mayors’ and citizens eyes when he promises supplementary means to protect our country,” Vincent Gilles told Belgian newspaper La Libre Belgique on behalf of the largest police union, SLFP Police.

Johan De Becker, head of the police zone that includes Molenbeek, said, “We need resources [in order] to investigate.”

He said Brussels is short 600 police officers.

Leman, of the Molenbeek nonprofit, said he would support having more local police officers who work with the community.

“A good cop who is friends with everyone can learn a lot. That’s what we need instead of repression,” he said.