Profiles: The major players

Al Jazeera looks at the Petraeus report’s key players and their influence on Iraq.

Nuri al-Maliki – Iraqi prime minister

|

| Al-Maliki has been under fire at home and from his US allies in recent months [AFP] |

Fifteen months ago Nuri al-Maliki was appointed as Iraq’s prime minister, in the hope that he was the man to bridge the nation’s growing ethnic and sectarian divides.

A Shia politician who fled to Syria in 1980 and then Iran after being sentenced to death by Saddam Hussein – the former Iraqi president – for his political activism, it was thought he would be strong enough to win over the Sunni and Kurdish minorities.

Once in office he was quick to prove his independence, criticising the treatment of Iraqi civilians by US-led multinational forces and pledging to crackdown on Shia militias.

In a bid to bring the violence in his country under control al-Maliki turned to neighbours Syria and Iran for help, with the tacit support of Washington.

But his support both at home and in the US has slipped away over time.

Nearly half of his cabinet has quit, including the main Sunni Muslim political bloc, which left the government, returned and left again.

Al-Maliki also had to watch as Shia groups fought on the streets of Karbala in recent days, with supporters of influential Shia leader Muqtada al-Sadr on one side and security forces controlled by the Supreme Iraqi Islamic Council on the other.

And his friends in Washington are also not coming to his aid any more. Several leading Democrats in the race for the presidency in 2008, including Hillary Clinton, have called for him to be removed, and even George Bush’s recent endorsements seem hesitant.

Al-Maliki knows the Petraeus report is not going to give him an ringing endorsement and has already moved to defend himself.

In a recent interview he said: “The positive development in the security situation is owed to national reconciliation much more than to our security forces or coalition troops.

“Some would like to hide this fact but it is a fact not to be hidden,” he said.

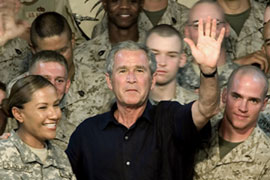

George Bush – US president

|

| Bush hailed his “surge” strategy during a visit to US troops in al-Anbar province [AFP] |

In less than one year George Bush will be out of office.

He will leave the White House and head home, a luxury he is highly unlikely to extend to the 168,000 US troops serving in Iraq.

The legacy of Bush’s war in Iraq is also expected to help decide his successor, as the opposition Democrats, now the majority in the US congress, have increased the pressure on the White House to withdraw forces.

Despite the deaths of 3,750 US troops since the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, Bush is standing his ground.

US commanders say it will take two years to pull troops out once a decision is made, but by then it will be a problem someone else will have to deal with.

And when General Petraeus delivers his long-awaited report it is expected to provide Bush with some breathing room, which he will use to attempt to redefine the conflict on his own terms.

If Bush can portray his so-called surge strategy – which saw thousands of extra troops deployed in an attempt to stabilise Baghdad and the al-Anbar province – as a success, maybe it will provide momentum for Republicans heading into next year’s election.

Last Monday, Bush visited US troops in al-Anbar and hailed the “success” of the strategy.

“Anbar is a huge province. It was once written off as lost. It is now one of the safest places in Iraq,” he said.

He also told them that any troop reduction would be based on “a calm assessment by our military commanders on the conditions on the ground”.

General David Petraeus – senior US commander in Iraq

|

| Petraeus was widely acclaimed for the way in which he pacified the city of Mosul [EPA] |

When Petraeus appears before the US congress, he is expected to deliver a report that draws a clear distinction between military progress and the near absence of any political improvement.

He took over as most senior military commander in Iraq at a time when more and more people were beginning to describe events on the ground as a civil war.

Petraeus’s task seemed impossible, with thousands of people dying each week and growing political divisions threatening to shatter any hope of reconciliation.

But hopes were initially high beacuse of the general’s wealth of experience.

He commanded the US army’s 101st Airborne Division during the Iraq invasion and won widespread acclaim for working with local leaders to pacify the northern city of Mosul.

The book he wrote on that experience has become something of a blueprint for succesful counter-insurgency operations. However General Petraeus stressed that a real understanding of local culture and politics, rather than overwhelming force, was the only way to win over hearts and minds.

In February he stood side by side with the head of Baghdad’s security forces as he launched his plan to stabilise the capital. Iraqi troops were going to be in the frontline of the so-called “surge” alongside the Americans.

And outside of Baghdad he sought alliances with Sunni tribal leaders. Outside of US control they have arguably done more to force al-Qaeda out of al-Anbar province in the past few months than the Americans ever have.

General Petraeus appears to be keen to show US congress that the cost of the surge strategy – in terms of money and troops – has been worth it and he is likely to cite a certain amount of evidence to that affect.

Ethnic and religious killings are reportedly down by 75 per cent on last year and more and more weapons are being seized by security forces.

But the main thrust of Petraeus’s report will have to convince US politicians that the surge can work, and that US troops should stay in Iraq.