Marcos’ legacy haunts Philippines

When Ferdinand Marcos came to power in 1965 he inherited a country whose economy was one of the most buoyant in Southeast Asia.

By the time he was thrown out exactly 20 years ago, the Philippines was broke and has been going backwards ever since.

Four decades ago, the World Bank saw the archipelago nation of about 7000 islands as another Japan poised for economic greatness in a region where China remained closed to the outside world and Singapore was still a backwater.

By the time Marcos was ousted in an army-backed People Power revolution in February 1986, the country and its economy was in a shambles.

According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the Philippines grew by an average of just 3.6% annually between 1970 and 2003 – the slowest in Asia among key developing countries.

Benjamin Diokno, an economist, told AFP: “Forty years ago, we were one of the leading economies in Asia; today we are nothing.”

Huge debt

Today, the Philippines is a country marking time as it struggles to meet its massive debt repayments and watches with envy as neighbours grow faster and prosper.

“After Marcos, there was a golden opportunity to put things right, but they blew it,” said business consultant Peter Wallace, who has lived in the Philippines for more than 30 years.

|

|

The Philippines is slow in growth |

“The same families that prospered under Marcos also prospered in the post-Marcos years – not a lot changed.

“The system stayed, the country continued its slide backwards and corruption spread into every facet of life.”

Last year, Berlin-based group Transparency International placed the Philippines 117th alongside Afghanistan, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Guyana, Libya, Nepal and Uganda as one of the most corrupt countries on earth.

“In the late 1950s and early 60s, the Philippines was being looked at as the next Japan,” said Diokno, an economist at the University of the Philippines and undersecretary for budget operations in Corazon Aquino’s first post-Marcos government.

“We were still getting money from Japan for war reparations, our mining and agricultural sectors were booming and we were cutting down our forests like there was no tomorrow,” he said.

High growth

“It was a period of very high growth and by the time Marcos was elected in 1965 we were growing by seven to eight percent a year,” Diokno said.

“Initially Marcos did a very good job; but by the time his second term came around, the rot had started to set in and his business cronies were taking all they could get. Then the (1973) oil crisis hit.

|

|

The Philippines has been going |

“Despite the country’s growing debt, Marcos was still the darling of multilateral lending institutions such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund who continued to pour money into the country.

“Debts started to mount, especially among his most trusted business associates. By the time Marcos left, the country was broke and we inherited a mountain of debt which has been accumulating ever since,” Diokno said.

Over the past six years, most government revenue has gone into paying down debt at the expense of much needed services.

For every 100 pesos earned by the government, 47 pesos is now spent on debt interest payments and key development indicators make for grim reading.

Reduced spending

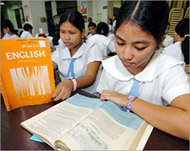

Spending on education has dropped from 3.4% of gross domestic product in 1999 to 2.4% in 2005, while spending on health has fallen from 0.5% to 0.19% over the same period, with infrastructure down from 1.8% to 0.73%.

Wallace said per capita income in 1971 was $206 in the Philippines – ahead of Thailand, Indonesia and China and just behind South Korea.

|

|

Spending on education has |

“The industrial sector was one of the most vibrant in the region while the country’s education system was among the best in Southeast Asia,” he said.

“In 1975, Thailand and the Philippines were roughly comparable. Today, Thailand is streets ahead of the Philippines in nearly all aspects of the economy and development,” Wallace said.

“(Thailand’s) economy is about twice that of the Philippines; its per capita income is almost three times that of the Philippines and so too are its exports. Thailand managed to attract $700 million in net foreign direct investment in 2004 while the Philippines could only manage $60 million.”

Population control

If the trend continues, Wallace said, the Philippines could even be overtaken by Vietnam on a per capita GDP basis in less than a decade.

“By the time Marcos left, the country was broke and we inherited a mountain of debt which has been accumulating ever since” Benjamin Diokno |

Wallace noted that in 1975 Thailand and the Philippines had roughly the same population of about 40 million.

Today, with a carefully maintained birth control programme, Thailand has 64 million people while the mainly Roman Catholic Philippines has 84 million and all the problems that it entails.

“You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to see that with low growth and a high birth rate, the country is struggling to stay afloat,” Wallace said.

Diokno agreed, adding: “That has been the case for the past 20 years. The question today is: Where do you start to clean the mess up?”