Fears over USA Patriot Act

Few laws in recent history have sparked as much controversy as the USA Patriot Act, passed by Congress less than two months after the 11 September 2001 attacks.

Federal law enforcement officials justified introducing the sweeping new measure as a necessary tool to investigate the lives of “suspected terrorists”.

Yet, in doing so, they aroused the ire of numerous civil liberties organisations which denounced the law as an assault on the basic freedoms of ordinary citizens.

Many Arab and Muslim Americans feared the statute would target their communities.

Secrecy

But more than two years after its inception, critics of the Patriot Act say that what they do not know about the implementation of the law is more troubling than what they do know.

“Our fears are that we still do not even know how it is being used and that is even more frightening to me,” said Laila al-Qatami, a spokeswoman for the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, a civil rights group in Washington.

Those opposed to the Patriot Act are faced with the challenge of substantiating their criticism of the law’s potential for abuse with hard evidence of its enforcement, a problem noted by former Republican congressman Bob Barr in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee in mid-November.

“Part of the problem, of course, Mr Chairman, with coming up with what traditionally might be thought of as hard evidence of abuses – that is, actual cases in which the government has abused the powers in the Patriot Act or other laws – is made necessarily difficult because of the secrecy, of course, that surrounds it,” Barr said.

Clarifications sought

In an effort to break down the veil of secrecy surrounding the law, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request in August of 2002.

|

|

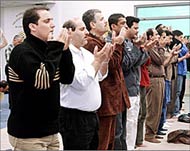

Many US Muslims stopped |

The ACLU asked the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the FBI for statistical information on their use of the new surveillance powers granted under the Patriot Act.

Early this year, the DOJ finally provided a response that ACLU attorneys deemed less than satisfactory. Many of the pages sent were blacked out under the rubric of classified information.

On 13 June 2002, the House Judiciary Committee sent the Justice Department a letter containing 50 questions related to the Patriot Act’s implementation. The DOJ responded by some vague answers, saying many of the details were classified.

Legal circumventions

Perhaps the most scrutinised section of the Patriot Act is Section 215, which made it easier for the government to secretly obtain personal documents such as financial, library, medical, phone and Mosque records with less stringent judicial oversight.

Under Section 215, the FBI must go to a Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court for authorisation to request private records, as long as it asserts that the order pertains to an investigation involving terrorism.

The individuals whose records are sought do not need to be notified and no probable cause that they are connected to terrorist activities must be demonstrated.

Civil rights groups argued that federal authorities could use Section 215 to target private citizens engaged in legal actions deemed threatening to the government. However, earlier this year, the Justice Department officials told Congress that Section 215 had not been used to date.

Still not used

At a House Judiciary hearing in May, then Assistant Attorney General Viet Dinh, one of the principle authors of the Patriot Act, told committee members that at least 50 libraries across the country had been contacted by federal agents about book records, but that Section 215 had not been used to do so.

Instead, law enforcement officials went to public courts for regular search warrants, according to one congressional staff member involved with the issue.

|

“Our fears are that we still do not even know how it is being used and that is even more frightening to me” Laila al-Qatami, |

However, just because the Justice Department said it has not used Section 215 does not mean it is not having a negative impact on certain communities, many civil rights advocates said.

“It doesn’t even have to be used, let alone abused,” ACLU President Nadine Strossen told the Senate Judiciary Committee in November.

Muslim fears

Strossen said the mere existence of Section 215 was creating a chilling effect among many Muslim Americans who “stopped expressing their political views because they are afraid that this power can be used against them.”

One of those individuals, Nazih Hasan, is president of the Muslim Community Association of Ann Arbor (MCA), which is part of an ACLU legal case challenging the Patriot Act.

In a statement issued in July, Hasan said he worried that the government would use Section 215 to solicit confidential telephone, email and business records of MCA members.

“We are very concerned that our political activities are likely to result in MCA members becoming the focus of additional investigations when we have done nothing wrong and have merely spoken out when we have disagreed with government actions,” Hasan said.

Authorisation

While the Justice Department claims not to have used Section 215 thus far, it “dramatically increased” its use of national security letters to “tap telephones, seize bank and telephone records and obtain other information in counter-terrorism investigations with no immediate court oversight,” a Washington Post story published in late March said.

|

|

Many Muslim Americans fear the |

National security letters, which existed well before 11 September 2001, allow FBI offices to issue administrative subpoenas without judicial authorisation. Under Section 505 of the Patriot Act, they can be used against US citizens, even those not directly suspected of illegal activities.

Another controversial section of the Patriot Act and perhaps the most widely used so far, is Section 213, which granted law enforcement agencies “sneak and peak” authority to secretly search private homes without prior notification and without informing homeowners of the searches until long after they are conducted.

A DOJ report sent to the House Judiciary Committee on 13 May said Section 213 had been used 47 times to delay notification of an executed search warrant.

On 15 occasions, the government has sought authorisation under Section 213 to seize property or records with delayed notification, the report said. Most delays have been no more than a week, it said. No details were provided on the nature of these investigations.

Misapplied

Although the DOJ report said the Patriot Act had “enhanced our ability to prevent, investigate, and prosecute acts of terrorism,” some analysts of the new law said it had been more commonly used in ordinary criminal investigations unrelated to terrorism.

Authorities have admitted using Section 213 search orders in non-violent, criminal cases, according to James Dempsey, executive director of the Centre for Democracy and Technology, a civil liberties organisation in Washington.

“These included the investigation of judicial corruption where agents carried out a sneak and peak of judicial chambers, a health care fraud investigation where they carried out a sneak and peak of a nursing care business,” Dempsey said recently in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Other criminal cases in which the Patriot Act was used include an investigation of a Las Vegas nightclub where financial records were subpoenaed under a section of the law. The case involved alleged bribery attempts made to local officials by the owner of the club.

Many critics of the statute said it was never intended to address this type of non-terrorist-related cases.

‘Harsh treatment’

Representatives from the Arab and Muslim community, when asked about the Patriot Act, often point to the use of secret evidence in post-9/11 detention cases.

|

“What we know is that thousands of Muslims have been arrested, detained and in some cases deported, and a culture of secrecy is developing that happened after the Patriot Act” Rashid Ahmad, |

Though they might not know for sure whether the Patriot Act was specifically used in any of these cases, many say they believe it is at the root of the Bush administration’s harsh treatment of Arab and Muslim immigrants.

“What we know is that thousands of Muslims have been arrested, detained and in some cases deported, and a culture of secrecy is developing that happened after the Patriot Act,” said Rashid Ahmad, president of the Muslim Civil Rights Centre based in Illinois.

Ahmad said he believed the Patriot Act was used in many investigations of Muslim Americans, though law enforcement officials often masked it in non-terrorism criminal charges.

“They do not use it on specific charges, but they use other laws on the books to charge somebody,” he said. “But how they got there is through the Patriot Act.”

Battle cry

For many, the Patriot Act is now a symbol of draconian government laws in the post 9/11 era, said Nancy Talanian, director of the Bill of Rights Defence Committee, an advocacy group based in Massachusetts.

For critics of the Bush administration who view the detentions at Guantanamo Bay as unlawful, and the hundreds of deportation cases involving Arabs and Muslims as grossly unjust, the Patriot Act is a battle cry for civil rights violations in America, she said.

“It has become, to some people, in some ways, a whipping boy for a whole host of other abuses,” she said.