The Arab Spring’s second wave

The current uprisings differ from their predecessors, marked by a series of more violent crackdowns.

|

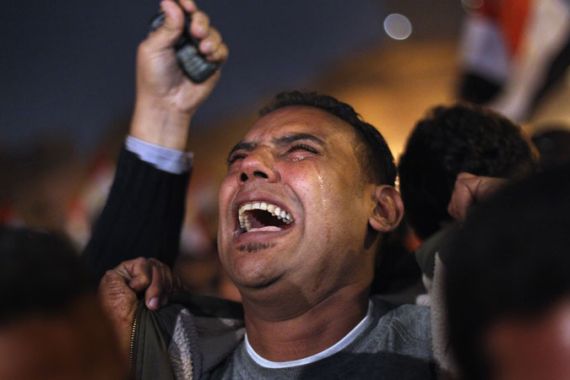

| Unlike the current uprisings, Tunisia and Egypt were characterised by quick transitions and the successful mobilisation of mass protest movements [GALLO/GETTY] |

With the Arab Spring stretching toward summer, the feel-good memories of Egypt and Tunisia are receding into the distance. Marred by ugly sectarian violence in Egypt and on-going scuffles between police and protesters ahead of the July elections in Tunisia, even the success stories of 2011 are permeated with unease over what lies ahead.

The world’s attention is now on a second wave of Middle Eastern uprisings – Libya, Yemen, Bahrain and Syria. These protests are characterised by the same quest for universal values as in Egypt and Tunisia in their early days of rebellion: freedom of expression, democratic reforms, an end to economic and political corruption, and a determined resistance to sectarian splits. Why then have they failed to yield even the short-term triumphs of their late winter predecessors?

Tunisia and Egypt formed a first wave of revolutions which resulted in quick regime turnovers, while Libya, Yemen, Bahrain and Syria comprise a second wave of much more contentious and drawn out dynamics. Initially, the strongmen of the second wave realised that they could outlast Ben Ali and Mubarak – who served as anti-role models, but the differences between the first and second waves of unrest are deeper than regime tactics. They go to the structures of the societies and their place in the international order.

A single cresting arc of protest

Tunisia and Egypt were characterised by relatively quick transitions and the successful mobilisation of non-violent strategy in mass protest movements. Even though it felt like a lifetime watching Ben Ali and Mubarak cling to the little power they had left, these revolutions only took two months combined to realise their main objectives. In the first wave, we saw the creative use of social media as a vanguard of the street protests and the active participation of women as well as men both online and on the streets.

Furthermore, Tunisia and Egypt surprised but did not undermine the international order. Although their patron powers, France and the US, were slow off the mark in backing the popular protests, once they declared allegiance to the protesters they jumped on the revolutionary bandwagon cleanly and decisively, even helping to ease their erstwhile clients from power.

While hundreds of people were killed and injured in each of these two countries, the violence took the form of a single rising and cresting arc that led swiftly to government collapse. The dramatic narrative structure of the first wave created a sense that similar transitions would spread throughout the region sooner rather than later. However, a different set of parameters emerged with the second wave.

The chronic violence of Libya, Yemen, Bahrain and Syria

In contrast, Libya, Yemen, Bahrain and Syria are characterised by heavy regime crackdowns featuring tanks, snipers, noxious gases and bulldozers, more effective coordination or co-option of the military and security forces and a chronic smouldering violence. In short, the fear factor (not acute and adrenaline fuelled, but chronic and deeply seated) has dulled the potency of the social media and the effectiveness of non-violent mobilisation. These regimes have not surrendered the streets to the people. When protest, fear and reprisal techniques develop simultaneously, sectarian ugliness could be just around the corner. This lethal combination threatens to derail the Spring in progress in ways that did not come to a head during the momentum of the first wave.

It is impossible to ignore the fact that the second wave protests tend to be male dominated affairs. Since the brutal Saudi and Bahraini take down of the Tahrir style protesters’ camps in Manama’s Lulu Roundabout, there are far fewer images of women and children protesting, the brave yet slightly off putting demonstrations of Yemen’s niqab-clad ladies (who give a new meaning to “Women in Black”) notwithstanding.

Another major theme in the second wave protests is that these unfolding cases have the ability to shake the geostrategic contours of the region. Whereas Egypt and Tunisia maintained US and French spheres of influence, the contests for Libya, Yemen, Bahrain and Syria have revealed the complexity and contradictions of the international alliance system of the region. Questions about future access to cheap and abundant Libyan oil complicates the NATO intervention’s goals and integrity. On the other hand, Yemen, a pliable US ally in the “war on terror”, inspires US reticence to tip the balance while leaving a chaotic landscape full of toeholds for lesser interventions. Bahrain was an easy morsel for the US to toss to its Saudi and other GCC allies. And Assad’s Syria, surprisingly, has been revealed as a lynchpin of Israeli stability.

For all these reasons, the US has held off from decisively upholding democratic aspirations that it has championed in Tunisia and Egypt (not to mention Iraq and Afghanistan). By the same token, US hesitance has provided opportunities for other second tier regional players (France, Turkey, Qatar) to take the lead in developing policies, while Germany, Russia, China watch from the wings. With the outcomes of these cases far from certain, and the dominant powers cautiously hedging their bets, the potential for disruption of the international status quo increases dramatically in the second wave.

The could-have-beens: Bulletproof and earthquake resistant

We can also learn about the second wave from the countries that didn’t tip into it. First there are the monarchies of the region that have demonstrated their “bullet proof” nature. As with the first and second waves, protesters under monarchies want answers to their economic, social and political discontents. However, some combination of the deep structures of patriarchy, the availability of a buffer government with prime minister to be thrown under the bus, and welfare payments presented as the monarch’s personal beneficence seem to have bought precious time and space for beleaguered potentates and taken the edge off protest movements in Jordan, Oman, and Morocco. Kings seem to reassure domestic and international constituencies with their invented traditions of permanence and gravitas.

An even more interesting category of could-have-beens of the second wave is what we are calling the “earthquake resistant” countries. Like buildings designed for seismic danger zones, these systems have movement and flexibility built into them (the hard way). These unlikely candidates for stability are usually thought of as perennial bastions of conflict – Lebanon, the occupied Palestinian territories, Algeria and (Arab) Iraq. Not only do the residents of these contested societies vividly remember the everyday horrors of war, but their deep historical sectarian social divides and the grab bag of political techniques developed over the decades for managing them have created systems that have internalised negotiation and horse-trading and that value stability.

These complex systems are now used to choosing compromise over zero-sum positions, and it is worth noting that each of them was designed by an occupying power to be divisible and conquerable (the Fatah-Hamas rapprochement notwithstanding). In the aftermath of brutal conflict and drawn out and unsatisfying political processes of reconstruction, each of these societies is a little more sceptical about whether the promise of reform is worth the risk of chaos.

By examining these counter-factual cases, we can identify the prime factors in the second wave explosion. Libya, Yemen, Bahrain and Syria have latent or dormant – but not acutely inflamed – sectarian or tribal divides. They have pseudo-monarchs with less than the usual meagre legitimacy of Middle Eastern kings. The notion of revolutionary republics with dissolute and odious heirs apparent (or self appointed kings) rankles more than post-colonial monarchies that have lasted a few generations. When the conflict comes, it activates papered-over social fault-lines that people had almost forgotten were there. Few people remember how ugly war can be, and Egypt and Tunisia provided an illusion of quick resolution.

A third wave of change?

The second wave of chronic, fitful, back and forth, exhausting conflicts that show no sign of resolution (from Libya’s brutal civil war to the slow motion rolling crackdowns in Bahrain) has allowed for another set of actors to emerge as power brokers. Regional players Turkey and Qatar, both with very strong (if not subtle) offensive and defensive media strategies, are emerging as a possible third wave of change. With their constituents largely satisfied, or at least not commanding the streets or media with spectacles of discontent, these more sophisticated regimes balance moderate traditionalism or Islamism with active and creative foreign policies that boldly go where superpowers fear to tread. The third wave of change is entrenchment and emerging regional empowerment rather than revolution for a very select club.

The questions that remain include whether the US will work out its double standards and loosen the shackles of entangling alliances to pursue policies more befitting its waning superpower status and legacy as the champion of democracy. Also, will Saudi Arabia, with its senescent network of ageing princes and soothing petrodollars, continue to be a power broker – or will it itself enter the second wave of protests? Either way, it is the third wave players, Turkey and Qatar, that may gain the most as the spring rolls into summer.

Leila Hudson is associate professor of Near Eastern Studies, Anthropology and History and director of the Southwest Initiative for the Study of Middle East Conflicts (SISMEC) at the University of Arizona.

Dylan Baun is a PhD student in the Near Eastern Studies Department at the University of Arizona and a SISMEC Research Associate.

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.