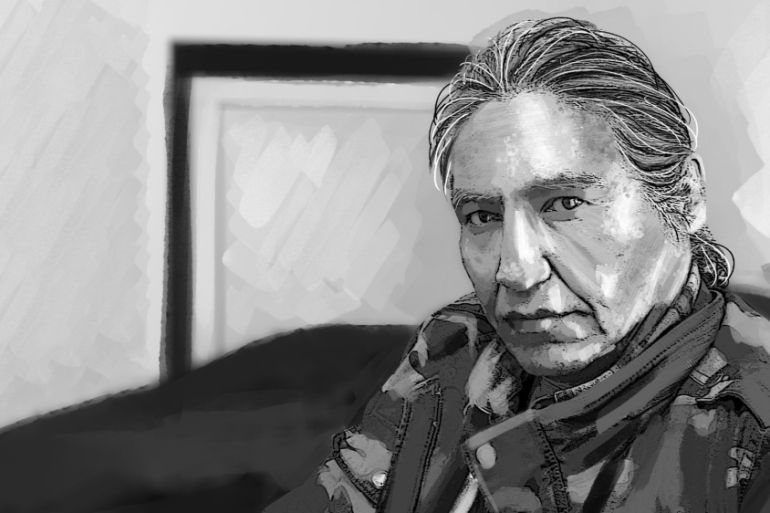

Chief Allan Adam on being beaten by police and Indigenous rights

The chief discusses the legacy of residential schools, making deals with the oil industry and the need for new treaties.

Fort McMurray, Alberta – It did not come out of nowhere. That is what Chief Allan Adam believes of the attack on him by Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) in the early hours of March 10.

A picture he took of his bloodied, swollen face later that morning, after he had spent hours in a Fort McMurray jail cell, made global headlines when Adam released it at a press conference on June 6.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhy are protests against France raging in New Caledonia?

‘No choice’: India’s Manipuris cannot go back a year after fleeing violence

Photos: Indigenous people in Brazil march to demand land recognition

The 53-year-old is Dene and the elected chief of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation (ACFN), located in the hamlet of Fort Chipewyan, approximately 300km north of Fort McMurray in northern Alberta.

He believes he was profiled by the RCMP outside of Fort McMurray’s Boomtown Casino because he is Indigenous.

Dashcam footage of the incident showed Constable Simon Seguin running towards Adam as he is about to be handcuffed by another officer. Seguin bulldozes Adam to the ground, punches him and puts him in a chokehold. The two RCMP officers then put him in a police car.

‘If we were white’

Adam says he is convinced the police who “tag-teamed” him were on anabolic steroids that gave them heightened strength. He is calling for all police to be tested for the drug because, he says, it is a rampant issue in the force that is not being talked about.

“They’re all jacked up on the stuff, man,” he says.

It is a muggy June afternoon, and we are sitting outside the Athabasca Tribal Council administrative building in Fort McMurray. He can’t talk for long, he says, because he has to be home in time for his granddaughter’s sixth birthday – his family is counting on him to be there. Still, he considers each question carefully before he answers. And when he does, he speaks authoritatively. In these parts, Chief Adam is well known and well respected.

For months, Adam’s lawyer had been requesting that dashcam footage of the incident be released. On June 11, after widespread media coverage of the story, the RCMP released a 12-minute video.

With red and blue lights flashing, Adam says an RCMP cruiser pulled up behind his truck in the casino’s parking lot. His wife, Freda Courtoreille, was sitting in the driver’s seat. His niece was also in the car. They were just about to leave and Adam, who says he was unaware that his licence plate had expired, the penalty for which is a $300 fine, was annoyed at being hassled by the police.

In the video, he can be heard telling the first officer on the scene, “Don’t f****** stop behind us like you’re f****** watching us.”

A little further on in it, he tells the officer to tell his sergeant that “Chief Adam f****** tells you, ‘I’m tired of being harassed by the RCMP.'”

At times during the exchange, Adam shouts, swears and adopts a combative posture. He had morphed into defence mode, he explains.

“We live in the 21st century now, and the way the police force treats us shouldn’t be happening,” Adam says. “When it comes to the treatment of First Nations in Canada, the police are nothing but a bunch of ruthless thugs.”

“I knew they (the police) were checking us out … if we were white, they wouldn’t have done that,” he adds.

|

|

Corporal Teri-Ann Bakker, the media relations officer for Wood Buffalo Regional RCMP, who also oversees community policing, said there was nothing she had seen to suggest the incident was premeditated. She had not spoken to the officers involved, Bakker said, adding: “There’s an ongoing ASERT [Alberta Serious Incident Response Team] investigation, so I can’t respond in regards to anyone’s role and thoughts.”

On the subject of anabolic steroid use, Bakker said, “I have never heard of that. If someone is concerned or has reasons to believe or suspect that [officers are using anabolic steroids,] then definitely report it.”

“The RCMP code of conduct is the following: integrity, honesty, professionalism, compassion, respect and accountability. And we expect all employees to act that way and members will be accountable when those values are not upheld,” she said.

But there have long been tensions between the RCMP and Indigenous people in Canada.

A troubled history

In 1873, the Dominion of Canada established the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP). One of its primary roles was to clear the plains of Indigenous people and make way for the settlers.

The NWMP later became the RCMP, and its foundational principles remained.

The RCMP helped to round up First Nations and herd them onto tracks of land known as reserves, which they then guarded, enforcing the Indian Act, an oppressive policy that dictated every aspect of the lives of Indigenous people and which still exists today.

The RCMP also helped to forcefully remove Indigenous children from their families to take them to residential schools where physical, emotional and sexual abuse was widespread, and thousands died.

The resulting intergenerational trauma remains to this day.

‘I knew I was done wrong’

The encounter between the RCMP and Adam escalated when the RCMP “manhandled” Adam’s wife, he said. “They tried to go after my wife. They knew if they got to her, then they had me entrapped.”

At one point, as he was taking blows to the head, Adam said he told himself to stay awake. He thought of the possibility of being killed and becoming another Indigenous statistic of police violence.

“I had a moment to snap out of it, and I was wide awake,” he says. “I said to them, ‘What’s wrong with you guys, I’m Chief Allan Adam.'”

Seguin is facing unrelated charges of assault, mischief and unlawfully being in a dwelling house from an incident prior to the attack on Adam. His trial is set to take place in a Fort McMurray courthouse on September 30. He remains on active duty.

On June 25, Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde called for Seguin’s immediate suspension: “The news that Const. Simon Seguin is still on active duty is unacceptable. The RCMP should suspend the officer … First Nations see the assault on Chief Allan Adam as unprovoked and unforgivable. To re-establish trust, the RCMP must address incidents of brutality head-on.”

When asked why Seguin was still on active duty, the RCMP’s Bakker said: “His duty status is the result of an assessment made by his managers.”

After being jailed for several hours, Adam was charged with resisting arrest and assaulting an officer.

“To me, it didn’t matter; I wasn’t worried about the charges,” he shrugs.

On June 24, the Alberta Crown dropped all charges against Adam. A statement from Alberta Justice said the Crown’s decision was made following “an examination of the available evidence including the disclosure of additional relevant material”.

“I wasn’t going to plead guilty to anything. I didn’t give a s*** if I went to court and if I was humiliated in court. I was going to walk out a winner because I knew for a fact I was done wrong, I was assaulted,” Adam says.

‘Rough and tough’

It was not the first time that Adam was assaulted by an authority figure.

The chief is a residential school survivor.

Between the ages of six and nine, he was repeatedly molested and physically and verbally abused at the federally funded Holy Angels school in Fort Chipewyan.

The aim of the residential schools, according to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), was to remove parental influence – spiritual, cultural and intellectual – from the children and to assimilate them into settler society. Adam was hit if he spoke his Indigenous language – Denesuline – and eventually lost the ability to speak it fluently.

Adam shifts in his seat and stares out across the gated grass yard when asked about the abuse he endured at the school.

“I thought I put that all behind me … People don’t understand this is the reason why people can’t deal with issues, because they keep bringing it up,” he says, his voice rising slightly in annoyance.

But then his tone changes and he begins to talk about the terrors of his childhood.

“I was molested. I was physically abused. Assaulted. I went and told the teacher and he took me to the skate-sharpening shop and molested me there, too. That’s the kind of deal I had to put up with. I got molested by a nun. I couldn’t understand what I went through as a kid … six years old. What they did to us in residential school is unreal.”

But Adam was born a fighter, he says. And it is that strength that helped him become one of Canada’s most powerful and prominent Indigenous leaders.

“I’m a quiet individual. I like to stay by myself. I try not to talk too much about politics. I try to talk about life and how the grass needs cutting. I like to hunt. Most of all, when I’m not working, I like spending time with my family,” he says.

He describes growing up in the remote community of Fort Chipewyan as a “rough and tough” life. Scrapping between the Dene, Cree and Metis People who lived there along the spectacular southwest tip of Lake Athabasca was commonplace. The boys were all coming into adulthood fresh out of residential school and learning how to survive in a white world – it was a confusing, frustrating time and place in which to grow up, he says.

Alberta’s oldest settled community

Fort Chipewyan is Alberta’s oldest settled community and a designated National Historic Site of Canada because it was once the epicentre of the fur trade.

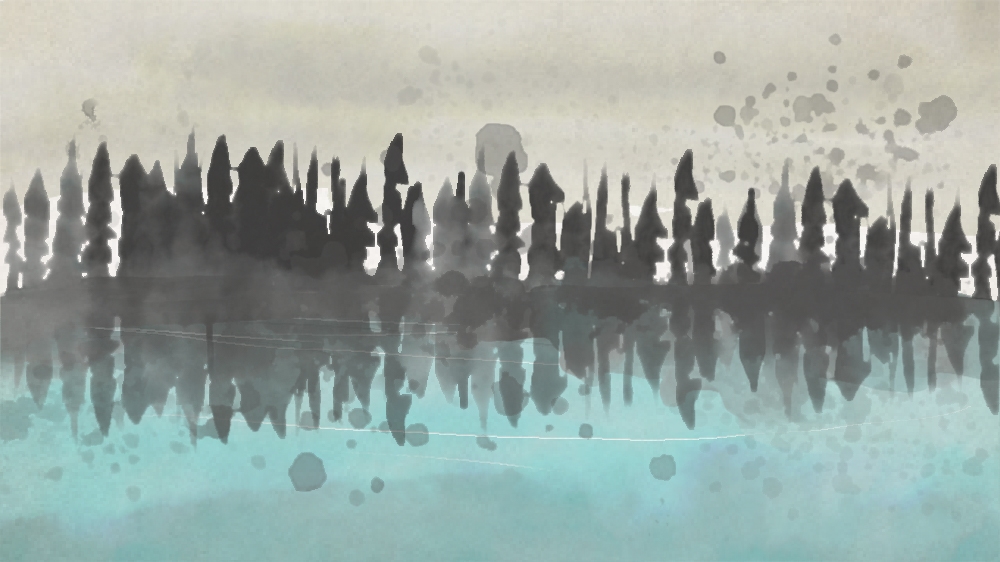

The area was rich with fur pelts and boreal wilderness through which hundreds of pristine water systems flowed, including the gateway to the Northwest Passage.

The Indigenous peoples navigated the unforgiving ways of the land and reaped the rewards of its abundance. And, at first, they worked alongside the newcomers in the fur trade.

But good relations did not last long. Among the brutalities committed against the Indigenous people of Canada was the distribution of smallpox-infected blankets. One of those thought to have participated in this in the Athabasca area was an explorer named Peter Pond.

“Peter Pond killed a Dene man,” Adam says matter-of-factly, pointing in the direction of a mall in downtown Fort McMurray that is named after Pond and which happens to be next to the Boomtown Casino.

Pond is honoured in Fort McMurray by the settlers as an explorer and leader in the fur trade. However, to Adam, Pond represents division, death and indifference to the oppression of Indigenous people.

A city built on oil

Nowadays, Fort McMurray is a city built on the back of the world’s largest industrial development: the oil sands – one of the world’s single largest oil reserves.

The black gold beneath the ancient bushland and sand dunes serves as Canada’s economic engine. For decades, people from across Alberta, Canada and the world have flocked to the city in search of wealth.

Good money can be made working in the oil sands. Most oil and gas workers do not need a high school diploma and can make more than $100,000 Canadian ($73,000 US) a year. The oil industry pays the highest wages in the country, albeit for sometimes-backbreaking, around-the-clock work.

In Fort McMurray, with a population of about 110,000, the resulting “good life” looks like souped-up diesel trucks, new schools and neat rows of cookie-cutter, top-of-the-line homes.

A main highway running through the city is named Confederation Way – after the Dominion of Canada and its colonies. There are neighbourhoods perched atop hillsides overlooking the mighty Athabasca River – one is called Eagle Ridge Estates, in honour of the bald eagles which once flourished in the area, but are being pushed out by encroaching development. There is every kind of amenity available in this fast-paced city surrounded by thick boreal forest.

Battling the oil industry

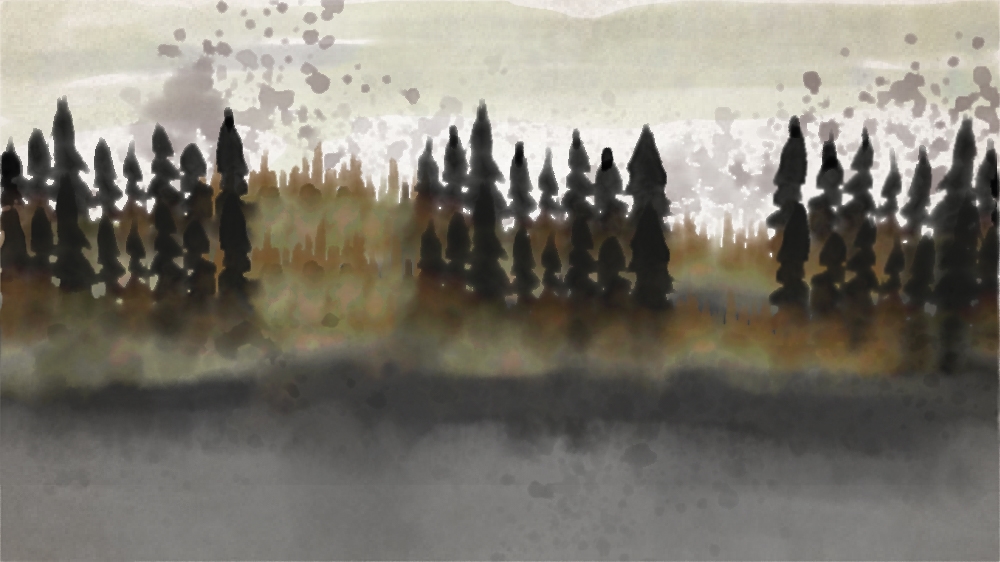

Fort McMurray may be far enough away from the oil-sands mining to appear unaffected by the dangers of the massive development, but the smell of tar still lingers in the air and on clear days, steady streams of smoke can be seen above the hills to the north of the city.

The pollution from the oil sands travels up the watery highway Chief Adam’s ancestors once used as a trade route – and flows towards Fort Chipewyan.

There has been discord here over natural resources for more than 300 years – first, with the fur trade; now, with the oil industry.

For years, Adam squared off against oil industry executives in a David-and-Goliath-style battle to protect his traditional territories from terrible damage.

His efforts attracted the attention of Hollywood, including actor and environmentalist Leonardo Dicaprio, who visited Adam in Fort Chipewyan in 2014 to learn of the Nation’s plight.

Adam also toured Canada with singer Neil Young to raise money for and awareness about the fight against the environmental impacts of the industry. He has lobbied world leaders to act to save his community from the contaminations of industrial pollutants upriver.

Arsenic and mercury have been detected in the river’s once pure water and found inside the bellies of animals.

In 2009, an Alberta Cancer Board study found Fort Chipewyan had a 30 percent higher cancer rate than should be expected, as well as higher rates of rare cancers.

Adam says too many people have died of a rare cancer called, “cholangiocarcinoma”, which typically affects one in 100,000 people. Fort Chipewyan has a population of less than 1,000. He links the rampant rates of cancer to pollution from the oil sands.

A change in tactics

But two years ago, Adam did an about-turn and reached a deal with oil executives to secure financial benefits for the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation.

Some people called him a sellout who gave up on the fight to save the environment. But Adam claims he could not stop the industry, so he switched tactics – making sure his people at least received financial compensation that was long overdue.

“What I did is, I went and fought for compensation for the Nation because of the high rates of cancer, pollution of our waterways, the continuation of the pollution of our natural foods. Who is going to compensate us for all of that when all of this is gone?” he says.

The resources deep under the ground rightfully belong to First Nations people who have never been compensated for that from which Canada has grown rich, he adds.

“Are we still supposed to beg for handouts from them? These companies here in Fort McMurray caused a lot of damage to the environment that they’ll never, ever be able to fix for 1,000 years. The government’s allowed it to happen with no compensation to the Nation.”

Environmental activist Greta Thunberg made a trip to Fort McMurray last autumn to meet the chief who had once championed environmental protection. He says she asked him why he backed down. He explained to her that it was his only option – and not to look at it as if the battle is lost.

“I fought to protect the environment, and I couldn’t do it,” he explains, throwing his hands up in the air and shaking his head from side to side. “But, at least we got compensated for it, and now, if we do things right, in the future, we could move away from that hell hole in Fort Chip because it’s not going to get any better. It’s going to get more polluted every day. What will happen when they’re (the oil industry) all done and out of here?”

Now, Adam meets with industry executives every six months along with other Indigenous stakeholders and says he calls the shots.

“They (industry executives and investors) don’t go to Canada; they don’t go to Alberta. They come to our Nation and ask us what we want … We have regained some sense of security that, at least now, we have something to stand up on if things were to go wrong. Whereas before we had less than four million in the trust fund, now you could say it’s probably well over $60m.”

The trust fund is set aside for future generations from his Nation.

“If I walk away today, when my term [as chief] is done, I’d walk away with my head held up high and not walk away with my head hung in shame, because I signed an agreement with industry. When I came into this position, we weren’t getting money from industry, today, we’re getting money from industry because of the impacts they’re doing to the land,” Adam says.

A slump in boomtown

Fort McMurray nearly burned to the ground in 2016 after wildfires forced more than 88,000 people from their homes and caused almost $10bn in damages.

This spring, on the fourth anniversary of the wildfires, the downtown and low-lying areas were submerged in water for days after ice jams in the Athabasca River triggered unprecedented flooding.

“It was evident on May 3, 2016, and it is evident today: we are a region of resilience,” Mayor Don Scott said in a news release from the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo on May 3.

A slump in the Alberta economy has caused real estate values to plummet in the boomtown. The average home once cost almost $600,000, but current prices average around $531,000 according to data from the Fort McMurray Realtors organisation.

Work in the oil sands is dwindling. The construction of pipelines to transport oil to market has stalled as a result of opposition from Indigenous groups, environmentalists and an uncertain fiscal future. Yet, the Alberta Conservative Government is relentless in its pursuit of financially backing a revival of the oil industry.

Adam knows oil money will not last much longer.

“I want to make sure the ACFN will be able to function as a Nation. Our Nation is still in the process of coming off an era of horrors – it’s ironic for me to be like this because I come from a time of trauma and always being told what to do. Do this, do that, don’t say nothing. That did not represent well who I am.”

At 14, Adam moved from Fort Chipewyan to Fort McMurray with this mother. He soon dropped out of school, where he was bullied because he was First Nations and says his learning ability was not “up to par”.

“I couldn’t adapt, couldn’t adjust to it. Kids were laughing at me. I couldn’t fit in. The racism. No one would play sports with me. My parents split up. I fended for myself. I didn’t back down from anybody,” he recalls.

Becoming chief

Being a chief was never on his agenda until someone from ACFN nominated him to run for council 17 years ago. He was making a steady paycheque driving a rubbish truck for industry, dumping for the big players. He was also working on healing from the nightmares of his past, he says.

Beginning in 2003, Adam served two terms as councillor at ACFN and in 2007 was elected chief.

At first, his wife Freda, who he met when he was 25 and she was 19 and they were both studying at community college, disliked him being away from home so much.

Adam has five children between the ages of 27 and 34 and 12 grandchildren. The couple have been together for almost 30 years, and it is Freda who is the backbone of the family, Adam says.

“I couldn’t do what I do without her,” he reflects.

She supports him and keeps him grounded, he adds. But she would like for him to be home more.

Freda, who was handcuffed and taken to jail with Adam but released without charge, helped calm him after the violent encounter with the RCMP. But, he says, she was traumatised by the incident.

“It took them (the RCMP) 70 days to apologise to me and my wife. It was because of pressure [from the media]. When the story broke, they apologised to me.”

“At first, I wanted to do something right off the bat,” he says about why he waited almost three months to go public with his story.

“The morning I got out [of jail], I wanted to put it on Facebook and tell everyone I got beat up by the RCMP and I wanted to create havoc in Fort McMurray. Believe me, I wanted to f***** ransack this f***** city. There were other chiefs available that were going to do it with me.”

However, on the advice of his lawyer and with the COVID-19 pandemic, he decided to wait.

But when video surfaced of the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police in the United States, Adam decided he could not wait any longer.

“I was mad. Then the young First Nations woman [Chantel Moore] got killed in New Brunswick, and the young man who got hit by a cop vehicle in Nunavut, and I thought to myself ‘this is enough.'”

“They’re (the police) doing it (violence) at a rate where they don’t even have a sense for human life any more.”

He spoke out because he has a platform and wanted to use his voice for those who do not, he adds.

A report released by the correctional investigator of Canada earlier this year revealed that more than 30 percent of inmates in Canadian prisons are Indigenous despite making up just 5 percent of the overall population.

Canada oppressed “Indigenous peoples here through the residential schools right until 1996, and they still do the same with the high incarceration levels of Indigenous peoples in the justice system. There’s no liberation for Canadian Aboriginal people,” he says.

A time for new treaties

Adam believes reconciliation between Canada and Indigenous people is going nowhere fast.

“If he (Prime Minister Justin Trudeau) wants to come clean, there’s so much that needs to be done. We’ve got the ‘Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls’ crisis that has to be implemented; we’ve got the TRC just collecting dust, child welfare crisis … If you can pull out how much money in just three months for COVID-19 benefits for Canadians? About a trillion dollars was it? But how many years have First Nations been under a boil water advisory in Canada?”

It is just a matter of time before Canada goes through an uprising similar to the protests that broke out in the US following the killing of George Floyd, he says.

“I think at some point and time there’s going to have to be a movement in regard to where First Nations take this issue. The ordeal I’ve gone through ended in the courts but doesn’t mean the ordeal is done.”

“For the people who went through the same experience I did, don’t give up. Don’t go into silence and don’t go into shame cause you’ve nothing to be ashamed of. Put them (the RCMP) up against the wall and say, ‘Look at what you’ve done.’ Let them be shamed,” he says.

As far as what will help stop police violence and systemic racism in Canada, Adam thinks it is time for a fresh start. Go back to the drawing board and create new treaties in the spirit and intent of the original treaties Canada was established on, he says; a sacred covenant of agreements to respectfully live side by side as sovereign nations and to share the lands and resources for all time.

“Maybe it’s time we open the Canadian constitution again and let’s start dealing with the Royal Proclamation that sets out guidelines for opening government institutions to take over Indian land,” he says as a grin forms across his face. “That’s not the case anymore; we know what they’re doing.”