How big a threat does coronavirus pose to wildlife in Africa?

From reduced funding to criminal syndicates, the threat to some iconic species could be unprecedented.

In the verdant rolling Chyulu Hills of Kenya, there has been a remarkable story of wildlife success. In 2003, the local lion population had almost been wiped out. Now they number 200 or more. But there are dangers approaching.

A few years ago, we filmed with the chief architect of this lion renaissance, ardent conservationist Richard Bonham. He flew us over the iconic African landscape in his old Cessna, its flying shadow spooking herds of zebra and wildebeest. The great bulk of Mount Kilimanjaro looming in the distance.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMelting glaciers, rising seas: Approaching climate tipping points

The climate crisis: Preparing for what’s already here

The US is back in the climate fight

“When I first got here, there were lions everywhere,” he said at the time, gesturing across the landscape below. “But the Masai were killing them as they always had done, spearing them in retribution when they attacked their livestock. And then they started to poison them. They would kill a whole pride at a time.”

Local numbers reduced to the point of near annihilation. Recognising the catastrophe that was about to happen, Richard helped set up a scheme which began to compensate herders for cattle lost to predators.

“The aim was to get the Masai who own this land, to use wildlife as their prime source of income. When that happened, they began securing their habitat, looking after their animals as they would their own cattle.”

The scheme worked its magic, and the lion population has rebounded with dramatic effect. But now, another threat looms, not just to the lion prides but to all wildlife, and to communities throughout the country and the continent.

Lodges closed

In Kenya, coronavirus has yet to take hold, but its economic effects are already rampant, especially in the area of conservation.

“Since mid-March, all tourist lodges in and outside the parks have been closed,” Richard told me this week. “From our perspective, the big hit here is a total loss of conservation and park entrance fees. These fees are essential to help pay for wildlife management and anti-poaching strategies.”

Richard runs the Big Life Foundation, which protects 1.6 million acres of wilderness on the Amboseli-Tsavo-Kilimanjaro ecosystem.

Richard said he did not think people will be travelling to places like Kenya until mid-2021 at the earliest, which means more than a year with no tourism revenue and the associated unemployment that went with that.

“This is a long time for wildlife areas to survive,” he said. “Infrastructure will deteriorate, and so will wildlife itself if investment is not made to combat poaching and habitat destruction.”

Poaching on the increase

Kaddu Sebunya of the African Wildlife Foundation tells me that the loss of tourism revenue means jobs are being lost on a big scale. That means people are getting desperate, and poaching for game meat is increasing.

“People reliant on tourism have lost income in a very short space of time and need to find ways to feed their families,” Kaddu explained.

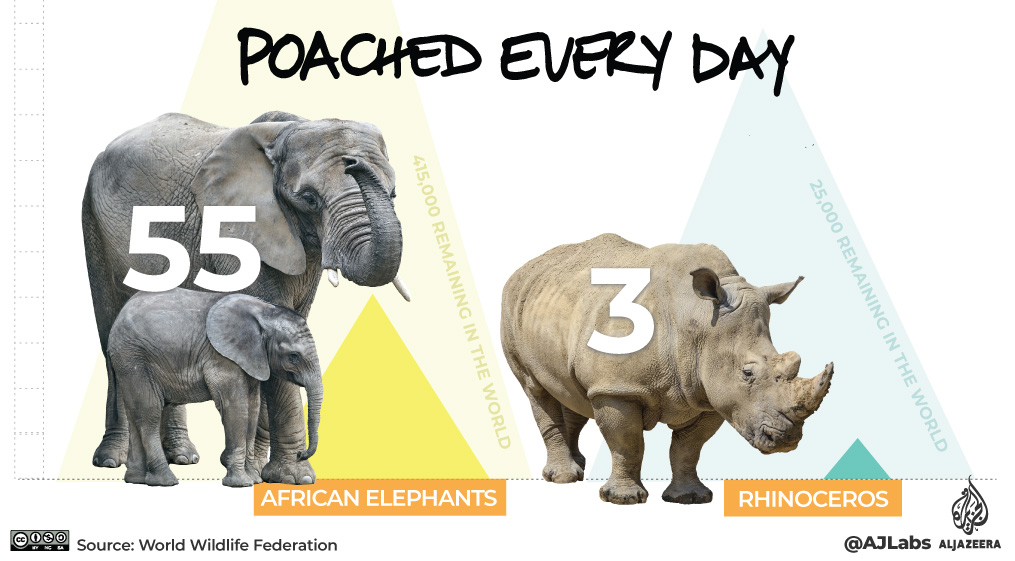

“Many are rangers, guides and experts who know wildlife and where it is. The temptation to poach will be extreme, and that includes endangered species.”

Illegal wildlife trade

Another likely side effect will be an increase in the illegal wildlife trade due to reduced human eyes on poachers funded by criminal syndicates.

“The poachers are bound to get emboldened – it’s already happening in Botswana,” Kaddu Sebunya said. “We’re hearing about increases of rhino poaching and more clashes between poachers and security officers, which have resulted in deaths.”

Fund communities

The bottom line is that rural communities urgently need funds to shield them from hunger and livelihood losses.

And that, says Richard Bonham, means international help, which is also needed to keep wildlife security programmes afloat.

“For us in the Chuyulu Hills, if we can’t keep funding going, the remarkable success we’ve had of getting lion numbers up from pretty much zero to 200 and more, will be simply and tragically reversed.”

Scale that up across a continent, and across myriad species from elephant to rhino, and you get the grim picture of what is at stake.

Your environment round-up

1. From the archives: Watch our film from 2011 on the return of the lions to Chuylu Hills.

2. Going hungry: Before the current crisis, an estimated 820 million people went to bed hungry each night. Now, an additional 265 million people face the threat of starvation by the end of 2020 due to drought and the disruption caused by the coronavirus pandemic. So how do we avert a humanitarian crisis?

3. Turn off the taps: Radical drops in emissions due to COVID-19 will “not be enough to slow the rise in global temperatures”, according to the UK Met Office. The International Energy Agency (IEA) reckons greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will fall by 8 percent in 2020, but climate scientist Richard Betts says it is not enough. “An analogy is filling a bath from a tap – it’s like we are turning down the tap, but because we are not turning off the tap completely, the water level is still rising”.

4. Plastic waste on Antarctic shores: Scientists have now found plastic waste in all the world’s oceans, including the Southern Ocean that washes around Antarctica.

5. Bio-luminescent waves dazzle surfers in California: After weeks of stunning surfers and residents of the US state of California, the especially vibrant bioluminescent ocean light show is now starting to die out.

Focus has to be on the survival of wildlife until such time tourism can bounce back. It is crucial to Africa's future, never more apparent than now.