Syrian refugee children process trauma through art

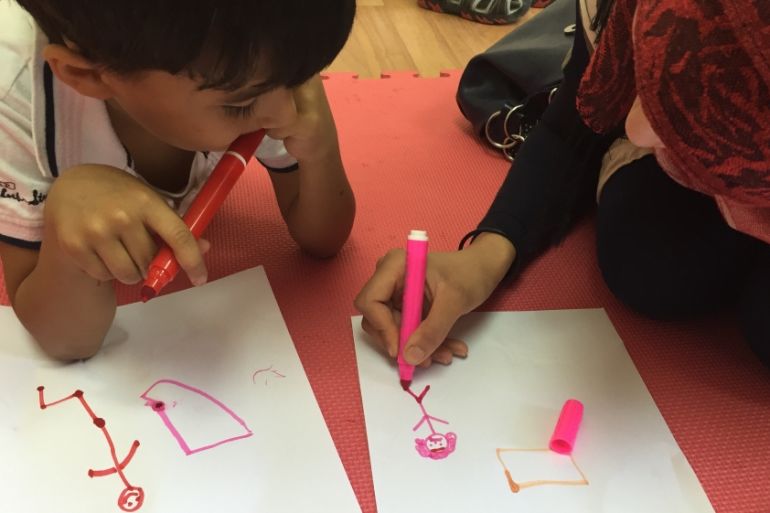

NGOs in Lebanon have been using art therapy to help children to deal with the horrific events they witnessed in Syria.

Beirut – Some Syrian refugee children process the trauma of war by drawing tanks and bloodshed; others focus their art on rainbows and flowers, images of happier times.

This is what art therapists working in Lebanon have found after years of working with Syrian children fleeing war in their home country.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIranian man loses bid to be freed from Australian immigration detention

Beyond borders: Migrants online

Tunis police raid sees refugees abandoned near the border with Algeria

“Art is a very effective way to work with kids,” said art therapist Dania Fawaz, who has collaborated with a number of NGOs that work with vulnerable youth, including Tahaddi, Himaya, Intersos and Caritas.

“Verbalising a traumatic event for a child – or even for an adult sometimes – can create so much anxiety that it hinders their capacity to express,” she told Al Jazeera. “A lot of children, especially the younger ones, haven’t developed the verbal skills they need to describe such horrific events, especially if you’re speaking about war. Art is a less directive and more natural tool for children to express themselves.”

READ MORE: Painting away the trauma of Syria’s war

Half a million school-age Syrian refugee children are registered in Lebanon and, although they are safe from war, they are now grappling with a lack of access to education and inadequate psychological care. Many have suffered extreme trauma, witnessing brutal violence and the loss of their homes, schools, friends and family members. Art therapy is one strategy for dealing with this unprocessed trauma.

Qualified art therapy is a relatively new field in Lebanon and requires practitioners to study abroad, as no degree is offered locally.

|

|

Myra Saad, the founder and director of Artichoke Studio, a registered art therapy centre in Beirut, said that it tends to follow a series of steps common to different branches of psychotherapy: “one, to have a safe space where you can express yourself; two, to become more aware of what you’re feeling and where it’s coming from; and three, to eventually change”.

The primary goal is to give participants “the space and time to be children again”, Saad told Al Jazeera.

“Especially with children who have been through a lot, they start to act out all the anger on others, and bringing them back to a place where no one’s going to hurt you and you’re not going to hurt anyone is a big change,” she said. “During the sessions, we give them time to grieve, because they lost a lot. We want to help them to regain a sense of control, so that they’ll be able to manage their anxieties better.”

Fawaz says that it is important to not pressure children to talk about the war, but instead allow them to come to it in their own time, or to approach it through metaphor.

![This art piece was from a project that brought together children from different socioeconomic backgrounds [Dania Fawaz/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/37ef221fd833494d9b5f3916fd9d850f_18.jpeg)

“Some children become extremely hyperactive after trauma, and some become extremely withdrawn, so I try to allow the children to decide at their own pace when they would like to start to revisit these memories,” she said.

“[Some] children who’ve recently arrived in Lebanon from Syria very quickly begin to draw images of chopped heads and the army tanks coming closer – very graphic images for a child to have seen… [Others] have lived through a lot and all they want to draw is rainbows and flowers, and this is what they need.”

The aim of the art therapy sessions is to help children to overcome symptoms such as anxiety, anger and behavioural difficulties.

Fawaz recalled how one young boy, having recently arrived in Lebanon from Syria, was constantly afraid to be alone. “If there was the sound of a plane, he would react the way he did in Syria, which was to duck for cover and scream in terror,” she said. “His mum was telling me that [since doing art therapy], he is able to go out alone. He is able to sit in class and listen. He’s able to make friends.”

Another boy, a 12-year-old who had been living in an area occupied by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant group (ISIL, also known as ISIS), reacted to the trauma of the extreme violence he had witnessed by becoming very aggressive.

“When he first came, it was image after image of war, and I allowed it to go on for as long as he needed it to go on for,” Fawaz said. “We would always discuss these images, and he would tell me about his memories. Eventually, through engaging in this process, his drawings were still of Syria, but became about the times when he used to play with his friends … We moved on recently to him drawing his current classroom and his current interactions with people. So it shows this real transformation.”

READ MORE: Coding classes open new doors for Syrian refugees

Although an increasing number of NGOs have been utilising art therapy, funding is often very limited and therapists are expected to work miracles in a short time. Saad and Fawaz both emphasise that they require at least eight sessions with each patient, ideally a dozen. Children with severe symptoms of trauma might need up to a year of therapy.

But even shorter, intensive blocks of treatment can have a positive effect. Art therapist Mona Shibaru worked with a group of teenage Syrian girls over 10 days in July 2016 as a volunteer for the Singapore-based organisation The Red Pencil, which runs art therapy courses worldwide.

![The aim of the art therapy sessions is to help children to overcome symptoms such as anxiety, anger and behavioural difficulties [Dania Fawaz/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/93d925021e614588a426d38b27dcb938_18.jpeg)

“There was a lot of imagery of war, of course – a lot of trauma,” Shibaru told Al Jazeera. “Images of yearning to go back home, images of death, loss of homes, displacement, separation from family members … and a lot of verbal processing of how to integrate into a community here while being displaced.

“Even though they’ve been interacting together for four years, they had never spoken about their experiences of leaving home or what they witnessed during the war … So this was not only a healing process, but also a process of bonding.”

No matter how long the treatment, Saad said, it is important to leave patients with a message of hope.

“We try to build some kind of resiliency that will stay with them even after the group finishes … We focus a lot on the power of imagination, because imagination and memories are things that no one can take away from you. No matter what happens, no matter where you move, you can still dream and imagine and envision.”