A Chinese American lesson for Trump

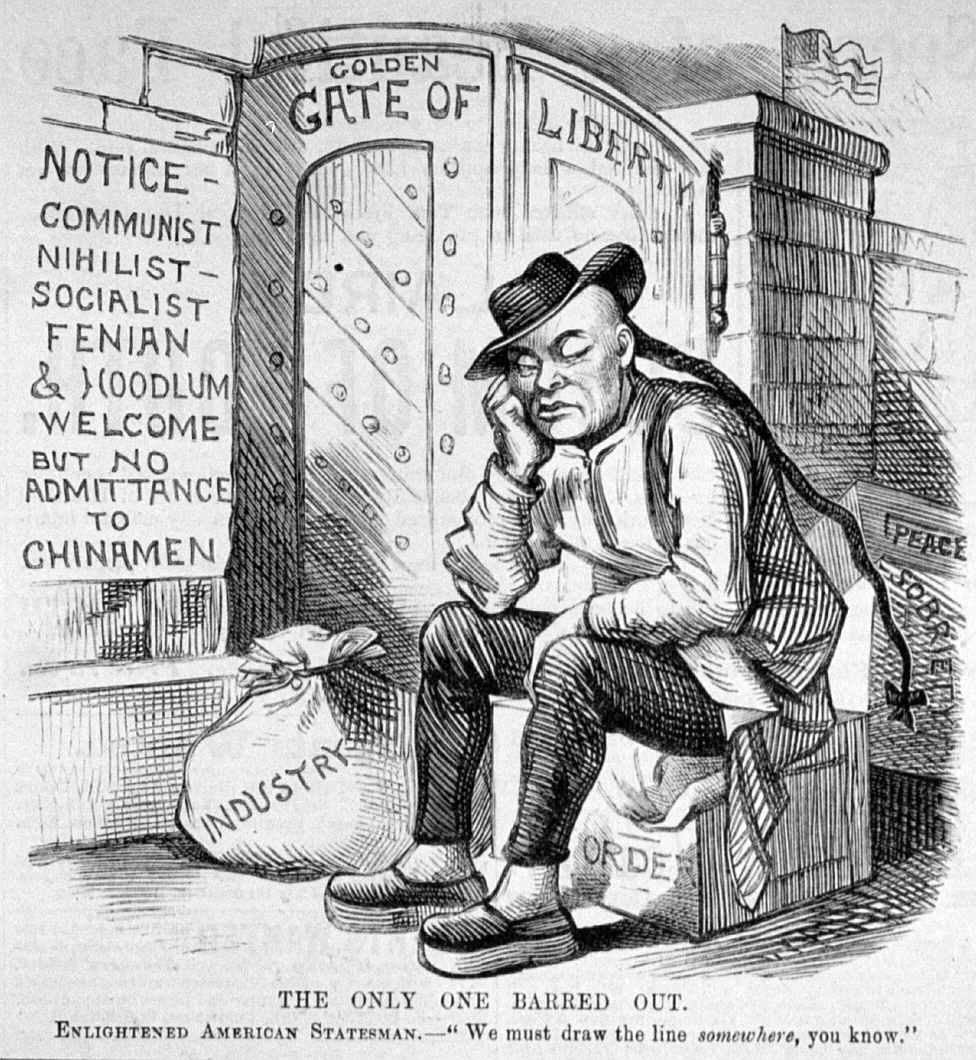

For Chinese Americans, the Muslim ban is a reminder of decades of discrimination under the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Los Angeles, United States – For some in the Chinese American community, Donald Trump’s executive order banning people from seven Muslim-majority countries is a little bit of history repeating itself.

Remembering how the earliest arrivals among them were targeted by discriminatory immigration policies, some Chinese Americans are cautioning Washington against repeating the mistakes it made more than a century ago.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS House passes bill to prevent another ‘Muslim ban’

Dreams dashed: Trump’s Muslim ban damage may never be undone

Will Biden’s repeal of Trump’s travel ban reverse its impact?

“We will look back on this Trump ban as a shameful chapter of US history,” said Bill Ong Hing, a University of San Francisco law professor who has worked to defend American civil liberties.

Hing explained that several organisations – San Francisco’s Asian Law Caucus, as well as New York’s Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund – are among the legal minds participating in the nationwide fight against the order.

For many in the Chinese American community, this feels all too familiar.

Scapegoats

The US Scott Act of 1888 barred Chinese – some of whom had residency permits and had lived and worked in the US for years – from returning after leaving the country, many to visit family back in China.

“There were several hundred Chinese in the port of San Francisco who were prevented from landing because of the act, similar to the folks at US airports this past few days,” said Gordon H Chang, a Stanford University American history professor who specialises in Asian American history.

The Scott Act affected 20,000 US residents of Chinese origin, Chang said. It was one of several modifications to the Chinese Exclusion Act, which, in 1882, aimed to stop immigration from what was a tumultuous, poorly governed, heavily colonised, Qing Dynasty China.

The Chinese, historians say, were scapegoated by the US administration as a cover for the country’s economic woes, which were entirely unrelated to Chinese immigration.

On its surface, the Chinese Exclusion Act and its aftershocks like the Scott Act had the effect of drastically lowering the Chinese American community’s numbers. But there were also other deeper and longer-lasting consequences.

“Obviously, this affected the size of the community, where they lived – in ghettos or Chinatowns – gender ratios, socioeconomic status,” Hing said, referring to how, in response to this state-sponsored discrimination, many Chinese Americans retreated to Chinatowns.

Chinatowns are today seen as entertainment venues, where Chinese Americans shop for groceries and sell food and trinkets to outsiders. But, historically, these were ghettos to which Chinese Americans had retreated in order to find community support against discriminatory laws and rampant hate crimes committed against them. The Chinatown phenomenon has continued until today, with many Americans of Chinese origin trapped in the generational poverty that Chinatowns represent for some.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed more than six decades after it was introduced, in December 1943 – and then only because it suited Washington’s diplomatic agenda of the day, explained Sue Lee, the executive director of the Chinese Historical Society of America. China had become a US ally against the Japanese during World War II.

“It politically wasn’t seemly to restrict the citizens of an ally,” Lee said.

‘It’s happening again’

There’s a lesson in what happened for the modern day, some say. And there are lessons to be learned from the Chinese American experience.

“The current ban on folks from the seven countries identified by Trump is similar in that these are blanket injunctions that are unsupportable by evidence that they did or will make any difference,” Chan said. “They are scapegoat measures pure and simple, pandering to public prejudices. Very dangerous.”

Lee agreed. “One of the reasons it’s important to know about it is to learn that, at one time, the US government singled out an ethnic group – the Chinese – from entering the US. That’s a lesson that we need to remember. And it’s happening again.”

READ MORE – Immigration ban: Hope trumps fear for Iranian-Americans

Los Angeles’ rapidly gentrifying Chinatown – the epicentre of a community that arrived in the mid-1800s to help build the US’s transportation infrastructure – was especially quiet on Sunday. And it was the second day of the Spring Festival or Lunar New Year, when many in the international Chinese community gather with family for celebrations.

Chinatown historical organisations – the Chinese American Museum and the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California – frequently host exhibits and events to commemorate the Exclusion Act, both to preserve and immortalise its place in the Chinese American saga, and for intra-communal posterity in the hope of preventing the enactment of new discriminatory immigration codes.

If there’s a particular lesson to be learned from the history of Chinese exclusion in the United States, it’s one of timing, according to Lee.

Trump on Friday signed an executive order banning people from Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen for a minimum of 90 days.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was initially signed into law by US President Chester A Arthur in 1882. It had come with an initial lease of 10 years. But then in 1892, it was extended by another decade. Finally, in 1902, it was renewed without limit.

Arthur served only a four-year term, but the law spanned 12 administrations with vastly different domestic and international policies. In other words, precedent shows that if such a policy is enacted, it may be extended indefinitely.

“That’s something that … we need to be aware of happening with these executive orders … They can be expanded and extended,” Lee said.

A history of resistance

Another lesson is that of Chinese American resistance. It is a source of inspiration to many in the Chinese American community that Chinese often stood up against the Exclusion Act and the series of measures, like the Scott Act, that also aimed to drive an entire ethnic community from the US.

One of the anti-Chinese laws mandated that Chinese had to carry photo identification on them at all times.

“The Geary Act of 1892 required Chinese in the US to carry photo identification certificates on their person at all times or face deportation,” Chang said. “Tens of thousands refused to comply by refusing to register.”

Another way that Chinese Americans resisted was to game the system, Lee explained.

After the 1906 Great Earthquake of San Francisco caused a fire that destroyed public documents, many Chinese came to the US as so-called Paper Sons, claiming to be the children of existing US residents.

Sue Lee’s own grandfather, Look Lee, was one such Paper Son. His – and her – actual inherited surname -are Wong. While this was something her grandfather kept a secret, having these false names is a source of pride – a reminder of resilience – to many modern-day Chinese Americans, she said.

And then there were those who tried to fight within the framework of the laws themselves.

“One thing the Chinese American people did was they fought. There were lawsuits. They sued. Chinese Americans stood up and fought for their rights. You have lawyers in the airports offering legal aid to fight the executive orders legally, so that’s something to learn from the Chinese Exclusion,” Lee said.

READ MORE: Six other time the US has banned immigrants

‘People don’t know about the Chinese Exclusion Act’

A lawyer for US advocacy group American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Mitra Ebadolahi, spoke to Al Jazeera from New York’s JFK Airport on Sunday, where she was helping to lead the charge in what she called “an army of lawyers” aiming to protect “precious freedoms”.

The lessons of the past – and the legacy of Chinese Exclusion – have often fallen on deaf ears, though, according to Lee. It’s still not part of the popular discussion on American history, she said.

“I think frankly people don’t know about the Exclusion Act,” she told Al Jazeera by phone, after returning home from a Chinese New Year family gathering.

Lee and Chang noted that despite official apologies from the US government, there have been no reparations made for the act that devastated Chinese American families.

Where Japanese Americans have received monetary compensation for their detention during the Second World War, Chinese families split apart by the Exclusion Act and the codes that compounded it have not.

“There isn’t the same feeling about the Exclusion Act as internment although it was discriminatory and unfair,” Lee said.