Hitler’s manifesto ‘Mein Kampf’ back in bookstores

Hitler’s ‘Mein Kampf’ is back on sale in Germany amid much controversy, discussion and criticism.

Hitler’s anti-Semitic manifesto Mein Kampf will be on sale in Germany on January 8, for the first time since World War II.

In accordance with European law, a copyright expires 70 years after the death of the author, whereupon the published writings are officially in the public domain.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussian wives demand return of reservist husbands fighting in Ukraine

Could today’s global conflicts bring World War III closer?

The Holocaust and the Politics of Memory

A team of six scholars from the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich led by Christian Hartmann will release 4,000 copies of the now 1,984 page book, which will include 3,700 critical annotations by the historians to demystify Hitler’s propaganda.

In the face of controversy over their decision to publish a new version of the book, with critics saying you can’t “annotate the devil“, the academics arguedthat the world is better off with their version in the mix.

|

|

“We are like a bomb disposal unit, rendering relics from the Nazi-era useless,” the author told ZDF, a German TV station.

“It’s 90 years since the book was written, so it has lost its power to influence people,” Hartmann commented further on the Heute current affairs show.

“Specific topics covered in it are forgotten in history,” Hartmann said. “We now have a critical reference to the book, which will work internationally.”

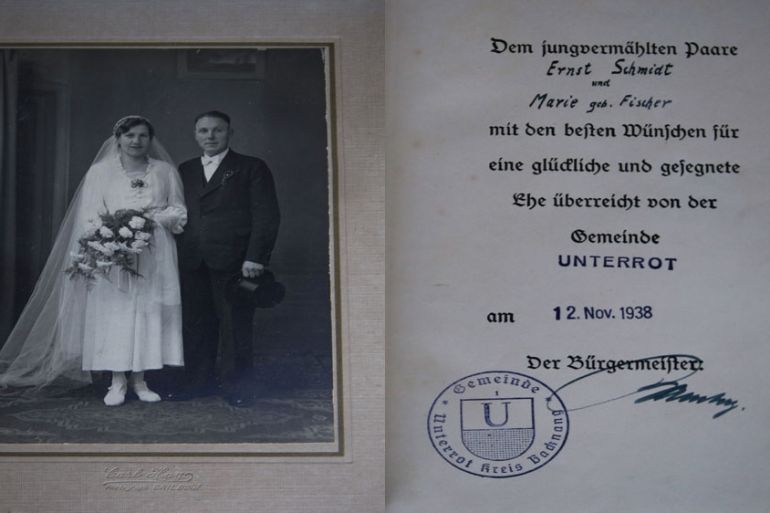

Mein Kampf wedding gift

One person who won’t be buying a copy is 100-year-old Lottie Franzen, who received it on her wedding day, like so many other Germans.

Speaking from her single-bedroom apartment in a suburb of Stuttgart, a city destroyed during the war by more than 140,000 bombs and 53 air strikes, Franzen said that she and her family lived in terror of the Nazis while they were growing up.

“We lived in constant fear of our lives. If you did something the SS didn’t want you to do, you were gone,” she said of Hitler’s dreaded security organisation. “It’s not a myth!”

“My husband and I married in 1940, and we got a copy of the book. I had a glance through it, but I remember thinking it was utter nonsense.”

The inscription on the first page of the book read: ‘To the newly wed couple, we wish the best for a happy and blessed marriage.’ On the next page, there was a photograph of Adolf Hitler and a date – 1937. Almost 800 pages of Hitler’s poorly written mumbled ideologies followed.

“My Scottish mother couldn’t bare the Nazis and found great difficulty in doing the Sieg Heil [Nazi salute] in restaurants when she was trying to have a meal, but you had to,” Franzen remembers. “You had to do it everywhere.”

Everywhere people went, Mein Kampf was stuck down people’s throats, she said. It was free so people received it at work, weddings, everywhere.

“Hitler wanted to instil ‘Kraft Durch Freude’ [strength through joy] and promised ‘good mood and fortune’, but as soon as the war kicked off in 1939, he changed his tune. My husband, brother and brother-in-law were called to service shortly afterwards. It was horrific,” she said.

Hitler’s best wishes for my the newly wed families were short lived.

Franzen’s husband was spared, but many women weren’t so lucky. Cities all around burned, colouring the sky in a constant red. With their men having departed never to return, the women were left alone to raise their families through unimaginable hardships.

For years, war refugees came to occupy their houses, as did American soldiers, taking up any available space, even living in the bathrooms.

“Children had to share one pair of shoes between themselves. There was no food, so you had to exchange carpets and other items from the house in return for it. Everything was destroyed,” she said.

D-Day

When the Americans arrived in 1945, the local population had to hide anything that appeared to have pro-Nazi sentiments, again for fear of death, Franzen recalls.

“We got rid of any newspapers or photographs depicting German soldiers. If they found Mein Kampf, they’d often burn your house down, so you had to be meticulous,” she said. “Much to everyone’s dismay, not all the Americans wanted to save us.”

Franzen said people thought being German meant being a Nazi. “And that just wasn’t the case. I remember one time, two Americans discussed how pretty my sister and I were, and then they followed it up with ‘shame they’re Nazis’.”

“Because [they thought] we were Nazis, we were treated badly and robbed and we couldn’t do anything about it,” said Franzen. In truth, “the men in my family who fought in the war and the [other] men I knew, [told us that] they didn’t know what was really going on with the Jews, that they didn’t know about the gas chambers,” she insisted.

After World War II

Once the war was over, no one discussed it for years. Children didn’t learn about Hitler in school and any time the war was mentioned it was when women were alone, mourning the deaths of their loved ones. Mein Kampf was cast into the corridors of history, never to be seen again.

Lion Feuchtwanger, a German-Jewish novelist and playwright, who took exile in France while the Nazis burned his books and took over his home, wrote in an open letter in the exile newspaper Pariser Tageblatt (Parisian Daily News) that he thought the “Fuhrer’s” 140,000 words were “140,000 offences against the spirit of the German language”.

But, Dr Edward Arnold, an assistant professor and lecturer in European Studies in Trinity College, Dublin explained that: “If you want to gain an understanding of the danger of irrationality in politics then Mein Kampf is an important read. In one of [my courses] my students study extracts of the book.”

“His poorly written, clumsy style reflects the way he spoke German and demonstrates how he saw politics. It is easier to sway people by using the spoken rather than the written word,” said Arnold in an interview with Al Jazeera.

“Hitler had contempt for intellectuals and understood early on that to succeed in politics a leader needed to appeal to the majority,” Arnold said.

A new Mein Kampf

It remains to be seen whether people will openly buy a copy of the book in a bookshop without feeling judged. It sold well online, in a less public format, where only two years ago, in January 2014, Mein Kampf topped numerous eBook charts including Amazon.co.uk’s “propaganda and spin” chart and its “Fascism and Nazism” chart.

In the United States, a 99 cent version topped the retailer’s “propaganda and political psychology” chart, The Guardian newspaper reported.

The imminent release of the book has made headlines around the world, and historians, experts and members of the Jewish community have been called on to comment. “How Dangerous is Hitler’s Mein Kampf Today?” one newspaper asked.

According to Josef Schuster, the president of the Central Council of Jews, not very. “Knowledge of Mein Kampf is still important to explain national socialism and the Holocaust,” he told the German Handelsblatt business daily newspaper.

It was Hitler’s aim to saturate the German psyche with his manifesto, of which 12.5 million copies were in circulation between 1933 and 1945. How many copies will be sold this time round is anyone’s guess.

In 2012, the Bavarian state government stated that it would support the annotated edition with 500,000 euros ($543,000) but pulled out citing concerns that it would offend families of Holocaust victims and survivors.

But no doubt “Der Fuhrer” himself would be happy to hear his book is not just online, but also back in people’s minds, 70 years after his death in an underground bunker in Berlin.

Franzen won’t be buying the book all the same.

“No thanks,” she said. “Annotations or not, I think I’ll pass. It’s not worth a possibility of a paper cut.”

Its initial printing run will be 4,000 copies and the book will sell for 59 euros ($64).