Education falls prey to Ebola in Sierra Leone

Amid lingering disease fears and economic fallout, most children have stayed away from recently reopened schools.

Freetown, Sierra Leone – It was clear things would be different as nervous-looking students took their seats at the Church of Christ Primary School set on a rocky hillside in Sierra Leone’s Ebola-ravaged capital.

“We’ve had a long holiday and we thank God to be alive,” announced sixth-grade teacher Andrew Kabia as he led the class in prayer. “But now we need to focus on our work and forget about everything that has happened.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUganda declares end of Ebola after 4-month outbreak

Uganda’s Ebola outbreak nearly under control, says Africa CDC

Ebola vaccines produced lasting antibodies during trial: Studies

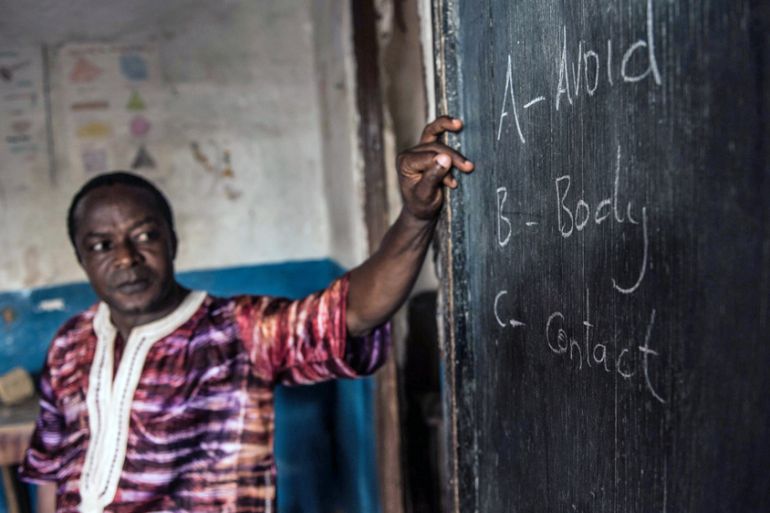

“You have already learned your ABCs,” he told them. “But now you must learn it again – Avoid Body Contact.”

As he wrote the acronym on the blackboard, the headmaster roved among the desks aiming a digital thermometer at the heads of his pupils.

RELATED: Down to zero: Recovering from Ebola in Sierra Leone

But the most dramatic change since Ebola swept across the country last July – forcing the school system to shut down completely – was in the number of students.

Out of a total of 150 pupils in class six, less than 20 actually turned up on a recent Tuesday. It is not unusual in Sierra Leone for the school year to start slowly, but this year’s figures were extremely low. A week later, classrooms were still not even half full.

Idrissa Kamara, 14, did not attend class. Al Jazeera found him wandering through the bustling streets of downtown Freetown, selling imported Chinese LED lights for $2 apiece.

![Idrissa Kamara wants to be a doctor, but had to leave school and find work to help pay his way [Tommy Trenchard/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/5117648e5526446bab3da8caee17e3b7_18.jpeg)

“My parents don’t have enough money now, so they were not able to register me,” he said shyly, his eyes fixed on the ground in front of him. “My mother told me to go and sell these so I can go back to school. But the work is not easy. Sometimes I’m out all day and hardly sell anything.”

While education is nominally free, some parents said they have to pay as much as 200,000 leones ($46) a year in unofficial teachers’ fees, as well as what they spend on books, pens, and uniforms.

Before the Ebola outbreak, Idrissa, who had dreams of becoming a doctor, was a student in the northern province of Port Loko, where his family farmed plantains and cassava, a local staple, which they sold in Freetown. But over the course of the last 12 months, the money dried up.

Between the restrictions on movement brought in to stem the spread of Ebola and the fear of markets and crowded spaces, small businesses everywhere have felt the pinch, leaving many families unable to continue supporting their children’s education.

Rob MacGilvery, country director for the British charity Save the Children, said along with lingering fears of public spaces keeping students away, many young people have been pushed into finding jobs to help their families deal with the economic pressures caused by Ebola.

“We’ve seen an increase in youngsters in petty trading, earning small amounts of money for the family. Now they’re in the habit of it,” he explained.

Such stories are common. One former secondary school student in the slum community of Kroo Bay said she turned to selling mangoes after the benefactor supporting her education had to withdraw the funding.

Buying mangoes at a dollar a dozen at the local King Jimmy market and selling them for 10 cents each, she can eke out a meagre living, but for now her plans to graduate and become an accountant have been put on hold.

“It’s too hard to find money now. Everyone has less after Ebola,” she said.

![Less than 20 out of 150 grade six students turned up on the first day at the Church of Christ Primary School in Freetown [Tommy Trenchard/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/c11601dadaef4a0ba56483c523cd9e37_18.jpeg)

Headmaster Bob Shiaka, who runs the Church of Christ Primary School in Tengbeh Town, is frustrated.

“Almost all of them are working,” he complained. “I see them in the market carrying trays. They used to do it on weekends, but they would come to school during the day… Now after Ebola, children are breadwinners too.”

The long break during the Ebola outbreak has exacerbated the challenges for an education system already wracked with problems.

In 2013, the last year for which data exists, a quarter of all children in Sierra Leone were not in school. Almost 50 percent of primary school teachers had no qualifications, and just one percent of grade four students could read “with sufficient fluency for comprehension”.

For the students who have returned to school, there is much ground to be covered. Lessons broadcast over the radio during the Ebola outbreak were seen as largely ineffective, so pupils now face an intensive four-month burst of study before exams scheduled for early August.

“Nothing like this has ever happened before,” said Save the Children’s Claire Bader. “There is no textbook for this.”

Follow Tommy Trenchard on Twitter: @TommyTrenchard