Cartoonists capture angst of Syrian conflict

Comics and cartoons portraying the ongoing violence are flourishing since the revolt began in 2011.

Amid bloody violence and brutal repression, art has emerged in Syria as a way to portray the tragedy of the conflict.

Comics and cartoons – once uncommon in Syria – have become a new and powerful tool of expression as fighting continues to rage. Cartoonists are depicting the uprising against President Bashar al-Assad’s rule in drawings, as well as conveying messages to the Syrian people and the rest of the world.

When Comic4Syria, a Facebook group that collects and publishes cartoons on the conflict, was launched last July, its creators were originally concerned the project would fail. That has been anything but the case.

“This is a very bloody and sad revolution. We were worried people wouldn’t accept the idea of cartoons,” the group’s Syria-based scriptwriter, who requested anonymity for security reasons, told Al Jazeera.

|

“With the revolution, political caricatures became a possibility. There were no fears of censorship anymore; cartoonists had a new platform to publish their drawings mainly on Facebook.“ – ‘Juan Zero’, political cartoonist |

Today, however, the group has more than 13,000 followers, many of them inside the war-torn country.

Six artists run the group, communicating and organising online with some inside and others outside Syria. Cartoons are published daily and comics are published twice a week.

“I write the scenario and share it online with the group of artists,” said the Syrian scriptwriter. “Then we discuss them and decide who will draw the comic.”

Grisly illustrations

More than 30 albums and dozens of cartoon stills can be found on the group’s webpage. Most paint a gruesome picture of the revolution, criticising the government for its repression and violence.

But the Syrian regime is not the group’s only target.

“Our comics shed light on everyone’s mistakes, the mistakes of the regime but also the mistakes of the opposition,” said Wassim Marzuki, a Syrian artist and contributor to Comic4Syria, who lives in Doha, Qatar. “Some comics also use humour and funny characters. It helps the viewer better deal with grisly situations.”

Although most comics are in Arabic, the group has made an effort to translate some of its work into English – the objective being to reach out to people outside Syria to help them understand what is happening in their country, they say.

“Cold” is a comic reportedly based on a true story that happened early in the revolution in the southwestern city of Daraa, depicting a father who was killed and his son captured by Syrian forces after they joined the rebels.

|

| Ali Ferzat was assaulted last year after his work angered some people in Syria [Reuters] |

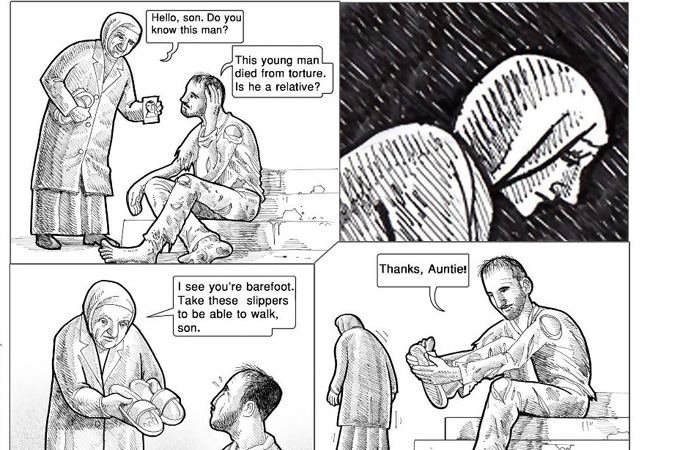

“Barefoot” portrays a mother searching for her son, only to learn he was arrested by Assad troops and tortured to death. The son was taken barefoot, and the mother tries to deliver a pair of slippers to him.

Another popular cartoon depiction of the conflict is “Chase“, which was dedicated to an activist killed by government soldiers. It portrays the futility of attempts by security forces to erase graffiti expressing dissent.

But the drawings don’t always take aim at the Assad regime. One criticises the international community for failing to help the Syrian people, showing world leaders looking confused at a maze-like map of the country.

Reaching out in pictures

Comics and cartoons have become a significant medium to express dissent in places such as Syria, where political repression is strong, one academic says.

Cartoons are subject to personal interpretations, they often use symbols, and audiences can draw conclusions on their own, making it harder for governments to provide physical and legal evidence to prosecute cartoonists, said Fatma Muge Gocek, a professor at Princeton University and author of Political Cartoons in the Middle East: Cultural Representations in the Middle East.

“Comics are not as direct as texts and their inherent ambiguity makes them hardly legally actionable,” Gocek said.

But the challenges of legally stopping the spread of political cartoons means repressive governments often resort to violence to quiet cartoonists.

Well-known Syrian political cartoonist Ali Ferzat was attacked in Damascus in 2011, and had both his hands broken by government troops.

Ferzat’s work, like that of others in his trade, never directly portrayed leaders in the regime, and the government initially tolerated his cartoons. But on April 2011, as the Syrian revolt kicked into high gear, Ferzat decided to portray Assad.

One of the cartoons, published before he was beaten, showed the president with a suitcase and the foreign minister trying to catch a ride with Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi in a speeding car.

The culture of comics and cartoons does not have a long history in Syria, and the recent prominence of artists portraying their country in drawings has been spurred by the revolution. While caricaturists were tolerated in the past, they had little freedom and could only cover social and cultural issues.

‘Blinded by power’

Juan Zero, a pseudonym, is a prominent Syrian cartoonist who fled Syria 10 months ago after the regime discovered his real identity. He describes his pre-uprising drawings as repetitive and boring.

“With the revolution, political caricatures became a possibility. There were no fears of censorship anymore; cartoonists had a new platform to publish their drawings mainly on Facebook,” Zero told Al Jazeera.

|

Zero became famous after a cartoon portrayed Assad wearing an oversized crown that had slipped down and covered his eyes, suggesting the president had become blinded by power.

The power of cartoons and comics comes from their ability to reach a wider audience, artists say. In places where literacy is low, images have great significance. Cartoons are also faster than words in delivering a message since they’re short, poignant and visually attractive.

“It’s a simple tool to tell a story. It can capture and insinuate more meaning than simple words. People can cry or laugh,” said Marzuki. “But what’s more important is that people don’t feel alone – their pain is shared.”

Members of Comic4Syria say after months of only depicting the dark side of the conflict, the group is now trying to spread messages of optimism as well.

“Some of our cartoons were too harsh and we are now at a phase where people are looking for hope,” said its scriptwriter. “So we are trying to put that hope in our images.”

The cartoonists say even if the Assad regime is toppled, their mission will continue. They pledged to keep drawing, criticising and raising awareness with one goal in mind: building a better Syria.