Anti-corruption debate divides India

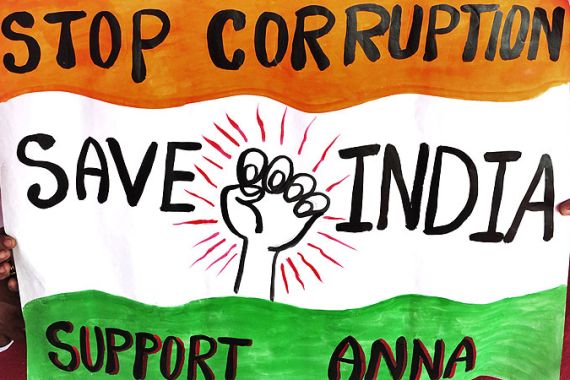

Millions across the country hit the streets in solidarity with Anna Hazare, but is the movement losing momentum?

|

| Anna Hazare, an anti-corruption activist, whose hunger strike garnered international attention, is sick – and his movement seems to have lost momentum [EPA] |

Six months after millions of Indians took to the streets protesting against corruption, the government has rejected anti-corruption legislation.

Anna Hazare, an anti-corruption activist, whose two-phase fast-unto-death catapulted him to national hero status, is sick and the movement he spearheaded seems to have lost momentum.

“The anti-corruption movement was a reflection of people’s anger and frustration. It was also the issue of maladministration and corruption in government agencies,” Nikhil Dey, a social activist associated with the National Campaign for People’s Right to Information, told Al Jazeera.

|

“The anti-corruption movement was a reflection of people’s anger and frustration. It was also the issue of maladministration and corruption in government agencies.“ – Nikhil Dey, Indian social activist |

Some degree of corruption has long been a seeming reality in Indian life, but a string of corporate scams – to the tune of some $40bn – involving senior federal officials has enraged the public.

Mismanagement and financial irregularities in the organisation of Commonwealth Games, which was almost on the verge of being scrapped, hurt the pride of India’s nouveau riche middle class.

Some analysts believe corruption is the biggest hurdle to India’s development.

According to a study released by Transparency International, a Berlin-based anti-corruption group, India ranked 95th of 183 countries on their corruption Index – equal placing with Albania and Swaziland, and behind Colombia and El Salvador.

The country’s bureaucracy was also voted the worst of 12 Asian nations by Hong Kong-based Political and Economic Risk Consultancy.

“After the economic liberalisation and globalisation, a huge chunk of India’s population has been left behind,” said Dey. “Even the middle class is frustrated, as it has also been facing the heat of tough economic choices, like price rises in basic amenities.

“Like the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street movement, Indians have similar questions about their government.”

Media participation

Nandini Sundar, professor of sociology at the Delhi School of Economics, said: “Anti-corruption protests were largely a middle class movement but many other social groups also participated. It’s an issue that concerns everyone. There have also been poor peasants’ movements against corruption, as in rural [province of] Rajasthan.”

“It is distinguished from other movements in that it had large middle class participation and the media supported it in a big way,” she told Al Jazeera.

Activists led by Hazare have been demanding a strong anti-corruption ombudsman or lokpal, but many have found the government’s response somewhat lacking.

The country’s media largely supported the anti-corruption movement, with TV news channels covering it extensively; seemingly every move watched, judged, transcribed and packaged for the nation-in-anger.

|

“The political class once again proved it was not sincere in its approach, despite such a huge agitation.“ – Prof Nandini Sundar, Delhi School of Economics |

“The issue of corruption caught the imagination of people. It also got political support mainly from the BJP [the main opposition party], though they [the BJP] were opportunist in their use of the issue and did not follow through in parliament,” said Prof Sundar.

The government finally presented its version of lokpal in parliament in December. The bill, however, was rejected in parliament’s upper house, as the ruling coalition lacks a majority in the chamber.

Activists had also criticised the bill as “weak”. They demanded that they be accorded the power to prosecute politicians, including the prime minister, and other state officials. They also demanded powers to act against corrupt judges.

Another bone of contention has been the status of the federally controlled Central Bureau of Investigation.

‘Insincere government’

But the government, led by the Congress party, seems to have ignored most of activists’ demands, and to the further chagrin of campaigners, it retained control of the office of anti-corruption ombudsman. This means the government is still solely reponsible for the ombudsman’s appointment and removal.

“The political class once again proved it was not sincere in its approach, despite such a huge agitation,” said Prof Sundar. “The political class managed to have their way as the lokpal bill they presented was very weak and with loopholes. They basically managed to betray the aspirations of the people.”

But questions arise as to why the government is seemingly so resistant to transparency in its operations, and to the appointment of an independent anti-corruption body.

| Al Jazeera’s Inside Story discusses the problem of corruption in India |

Yamini Aiyer, director of Accountability Initiative, a New Delhi-based think tank, said it was because of the “unique evolution of [the] Indian state”.

“The evolution of the modern Indian state was such that it created spaces for patronage dispensation in Indian polity. So, access to state system was by state patronage,” she said.

“It is part of the colonial legacy, that bureaucrats are meant to be opaque, outside of democracy and [to] wield power without accountability. In fact, there is a culture of secrecy.”

The government said Anna Hazare’s idea of lokpal was too broad and that it would affect the balance of democratic institutions, but the activists say the government was simply dragging its feet and that it was not serious about fighting corruption.

A slighted government and an over-confident “Team Anna” now held a string of meetings to thrash out the content of the much anticipated bill, but the debate swiftly degenerated into personal attacks and character assassination.

What followed was a war of words between activists and government officials.

Credibility issues

Amid the din of polarised debate, some crucial bills went almost unnoticed.

“No-one is paying attention to three other bills that were introduced in the parliament that are equally important in our fight for more transparency and accountability from the government,” said activist Dey.

“[The] grievance redressel bill, the whistleblower protection bill and the judicial accountability bill are the laws which will help people in getting their work done. This way, people will fight for their own right,” he said.

The credibility of Hazare and his supporters also came in for criticism, after one of his aides was accused of corruption.

|

“The problem of corruption is much more deep-rooted. It is to do with the nature of the political and administrative structure in our country. We need political and administrative reforms.“ |

Many also questioned him for not raising the important issue of corporate corruption.

“Neither lokpal [the government version] nor janlokpal [Hazare’s version] talk about corporate scams. The whole agitation got momentum after the 2G scam but Anna’s team did not make corporate scams the central focus,” added Prof Sundar.

Dey concluded: “I don’t see a solution in police force, as lokpal might become a problem if its entrusted with too [many] responsibilities and power. What’s the guarantee that a powerful lokpal won’t be misused?”

Aiyer said: “The insistence on the lokpal law is obfuscation of the main issues.”

“The problem of corruption is much more deep-rooted. It is to do with nature of political and administrative structure in our country. We need political and administrative reforms,” she said.

Hazare should have pushed for these structural changes, she maintained.

“If you are not attacking at the roots, it is just a band-aid.”

Role of online social networking

The social networking sites played its own role in the massive public campaign and creating buzz online. Feedback and updates were being constantly appearing and the group India Against Corruption quickly had more than five million online followers.

Online space became the virtual battleground between Hazare supporters and his opponents.

Joy Das, a Mumbai-based advertising executive who was active in the Twitter debate, told Al Jazeera: “There was a lot of positive response for Anna on social networking sites, particularly Twitter.

“However, as the agitation continued, his fight against corruption became like a political front. At one point of time the organisation India Against Corruption started looking like India against [ruling party] Congress.

“On Twitter, many of Anna’s supporters led sustained attacks on individuals who did not agree with their ideas. Anyone who criticised Anna was branded pro-government. It’s wrong, it’s like [George] Bush’s ‘with us or against us’.”

Like many other issues, the corruption debate has also been politicised – and people are divided on the issue. But reports from the ground paint a bleak picture of what seems to be endemic corruption.

Even WikiLeaks shed light on the entrenched corruption in India through leaked US diplomatic cables.

But academics and policymakers say corruption can only be prevented if structural and technological changes are brought to bear. According to a new book, Corruption in India: The DNA and RNA, public officials allegedly pocket about 1.26 per cent [$18bn] of India’s GDP through bribery.

Laveesh Bhandari, co-author of the book, told Al Jazeera that India needed to “create a lot of institutions with accountability”.

“We need to be rewarded as well as punished,” he said. “But [the] punishing is not happening. See how poorly anti-corruption bodies are functioning in the country – for example, the Chief Vigilance Commission [and] the Central Bureau of Investigation. If they are not punished, they will do what they want.

“There is poor use of IT and lack of monitoring. IT can be used to look into the process so that all the processes can be monitored, and it needs to be done on a massive scale.”

According to a Transparency International survey last year, more than 60 per cent people in India said ordinary citizens could make a difference in the fight against corruption.

“2011 was indeed the year of lokpal,” said Prof Sundar. “The agitation put the issue of corruption on the political agenda.”

The battle for lokpal seems now to be stuck in limbo – but the war against corruption is far from over.

Follow Saif Khalid on Twitter: @msaifkhalid