Africa: The first 50 years

Profound changes over the past decade mean African countries can now treat their former colonial rulers as equals.

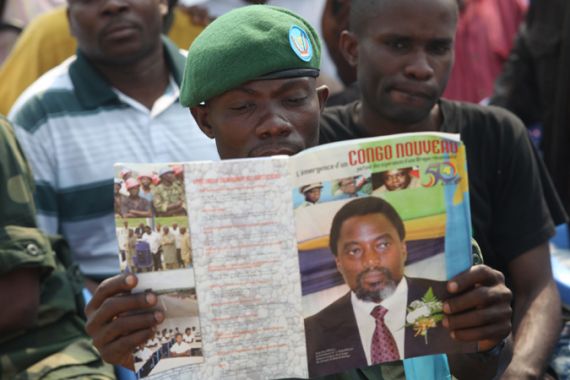

|

| Seventeen African countries gained their independence in 1960, but by 1968 there had been 64 coups or coup attempts [GALLO/GETTY] |

Fifty years ago 17 African states celebrated their independence from Britain, France and Belgium. There were high hopes that resource-rich Africa would flourish. A cartoon at that time depicted the map of Africa as a growing giant bursting out of his chains. In Nigeria the main newspaper, The Daily Times, had one word on its front page on October 1, 1960: “Freedom.” That expressed the wave of optimism that had surged across Africa.

The Daily Times’ editorial that day read: “Two great assets we have inherited from the British – parliamentary democracy and the rule of law. We shall firmly uphold these principles. And we shall do more. We shall jealously guard the sanctity of our constitution and our fundamental human rights.”

Cold War lenses

But by 1968 there had been 64 coups or coup attempts in Africa. Within two decades only two parliamentary democracies survived; Gambia and Botswana. Only Botswana out of the continent’s 53 countries has remained a well-governed democracy for 50 years. The rest became a mix of one party states and dictatorships, many of them military ones.

The Portuguese territories, Mozambique, Angola and Guinea Bissau, had to wait for independence until a coup in Portugal in 1974, Rhodesia only became Zimbabwe in 1980 and all South Africans finally got a vote in 1994.

The newly created countries emerged into a harsh world. Independence coincided with the beginning of the Cold War. The US and Europe and the Soviet Union and its satellites, cared more about whose side these new leaders were on, than what actually happened to their people. Human rights and democracy were shelved, dictatorships flourished supported by Moscow, Washington, Paris and London. Real freedom and development were ignored. Everything was seen through the lenses of either communism or capitalism.

Meanwhile outsiders co-operated with rich and powerful Africans to loot the continent – literally. According to the Washington-based organisation, Global Financial Integrity, a staggering $854bn – at least – was drained from Africa in illicit financial outflows between 1970 and 2008, much of it through mispricing by multinational companies. As political instability was compounded by bad management inward investment dried up.

Artificial creations

All this could only happen because the new governments – and the states themselves – were weak. They were artificial creations, new states based on the lines drawn on maps of Africa by Europeans at the end of the 19th century when they carved up Africa between them. Existing political boundaries were disregarded by the imperial powers so that old societies suddenly found themselves divided between French, German and British rule.

One can speculate about what might have happened if Africa had reverted to its pre-colonial political entities at independence or what it might be like today if it had never been colonised at all. But, achieving independence quite suddenly, the new African nationalist leaders decided that they would simply take over the colonial state and run it themselves.

But beneath the surface of Nigerian or Ivorian nationalism, the old ethnicities and their power structures survived. The European imperialists had ruled long enough to destroy or compromise the leadership of the old African societies but had not stayed long enough to replace it with something new.

They had also ruled their possessions by playing divide and rule between different ethnic groups. Now these different peoples were all supposed to come together as a new nation – though no nations had yet been formed. There was no common understanding of what Cote d’Ivoire or Nigeria should be. The latter has more than 400 different languages and huge cultural, social, religious and political differences between its peoples. Suspicion and mistrust created a winner-takes-all attitude at the top.

Out in the rain

|

| Nigerians living in London celebrate their country’s independence [GALLO/GETTY] |

The new rulers denounced the old kings and chiefs as primitive and backward – and asserted themselves as modern and progressive. They drew their authority from being “nationalist” and created various ideologies to try to unite their people behind them – Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire and Jean-Bedel Bokassa in the Central African Empire created royal, even divine, personality cults.

Compromised by years of collaboration with the colonial rulers, the old rulers were unable to reassert their authority though many of them continue to this day to wield considerable influence beneath the surface.

Chinua Achebe, the Nigerian novelist, thought the new democracy allowed the wrong people to take control.

In A Man of the People, published in 1966, he saw the new states like a house that the white man had built, lived in and suddenly left. All the Africans had been out in the rain until that point. Then at independence “the smart, and the lucky but hardly ever the best had taken it over and barricaded themselves in”. They then declared that the battle had been won and all debate must cease or the house would fall down. Most Africans might say they were still out in the rain.

Many of the new rulers saw their job as “catching up” with the first world by building modern states and societies. They borrowed hugely to build grand national institutions from state palaces to stadiums and created huge national bureaucracies copied from Britain and France.

When the 1974 oil price rise hit, they borrowed even more to keep their plans on track. The debts should not have been a problem if real development was taking place to service them. But it was not. Political instability, economic misrule, lack of capacity and corruption all played their part in diverting and wasting efforts to develop the continent. Existing infrastructure and institutions were not maintained. National currencies collapsed, impoverishing ordinary people but benefitting the rulers who had access to dollars and overseas bank accounts.

Wrong economic medicine

By the end of the 1980s most African countries were indeed in a bad way. The end of the Cold War gave the West – which had always believed it could tell Africans what to do – the chance to impose its own solutions. The West’s new agenda was democracy, respect for human rights and the free market.

Africa’s economies were handed over to World Bank and IMF economists. “Structural adjustment” introduced a dose of tough economic medicine that would restore the patient to health. Governments were forced to let the “free market” decide the value of their currencies, cut public spending and sell off their assets.

As a theoretical economic solution it might have looked right, but on the ground in Africa it pushed up prices, impoverishing all but a few, and destroying Africa’s professional classes by reducing the value of their salaries. Those in power who had mismanaged things so badly, now sold run-down state assets to themselves at knock-down prices.

The West also pushed African governments to hold elections and several dictators were toppled and military dictators forced to step down. But instead of releasing a wave of democracy as it had done in Eastern Europe, the sudden end to superpower-backed dictatorships and repression led to rebellion and civil war. By the mid 1990s more than half of African countries were suffering civil wars or serious civil disturbance.

Crossing the ‘last frontier’

But while the media fed the world a diet of war, disease and poverty from Africa, profound changes were taking place at the end of the 20th century. China had targeted Africa as the supplier of much-needed raw materials. Suddenly Chinese companies, state-owned and private, were going where Western companies feared to tread. That pushed the value of Africa’s raw materials and also gave African governments an alternative to Western partners. It gave them revenue and economic and political bargaining space.

Secondly, mobile phones arrived. Even the makers of them had no idea how quickly they would catch on in Africa. With few fixed lines, mobiles were bought in multiples of the predicted sales. Suddenly everyone found that Africans were a lot richer than the World Bank figures asserted and instant communication transformed business, big and small, in Africa.

The phones opened up political space as well as new commerce. Elections became harder to rig. Texting meant information, good and bad, could spread virally. Governments could not control it.

Thirdly, a new professional class began to emerge. Many of them had been educated or worked outside Africa. Inspired by a vision of Africa’s potential, they returned determined to do business according to international standards. Directly or indirectly they contribute to political stability as well and, most significantly, they are confidently both African and European. They have bridged the dichotomy their parents’ generation found so difficult between being African and Western.

The problems have not gone away: Corruption, poor governance and low capacity and the long term challenges of a rapidly growing population, environmental change and threats from diseases. But African economies have now enjoyed a decade of real growth and survived the global recession of 2008.

China with its 100-year horizon is committed to a long engagement and an alternative trading partner. That boost has drawn in other emerging economic giants, countries such as India and Brazil. Five years ago Africa was still “the last frontier”. That frontier has been crossed and there is no going back. This new engagement also makes it easier for African countries finally to treat their former colonial rulers as equals not masters.

Richard Dowden is the director of the Royal African Society and author of Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.