In Pictures

‘Preventive conservation’ at Venetian palace

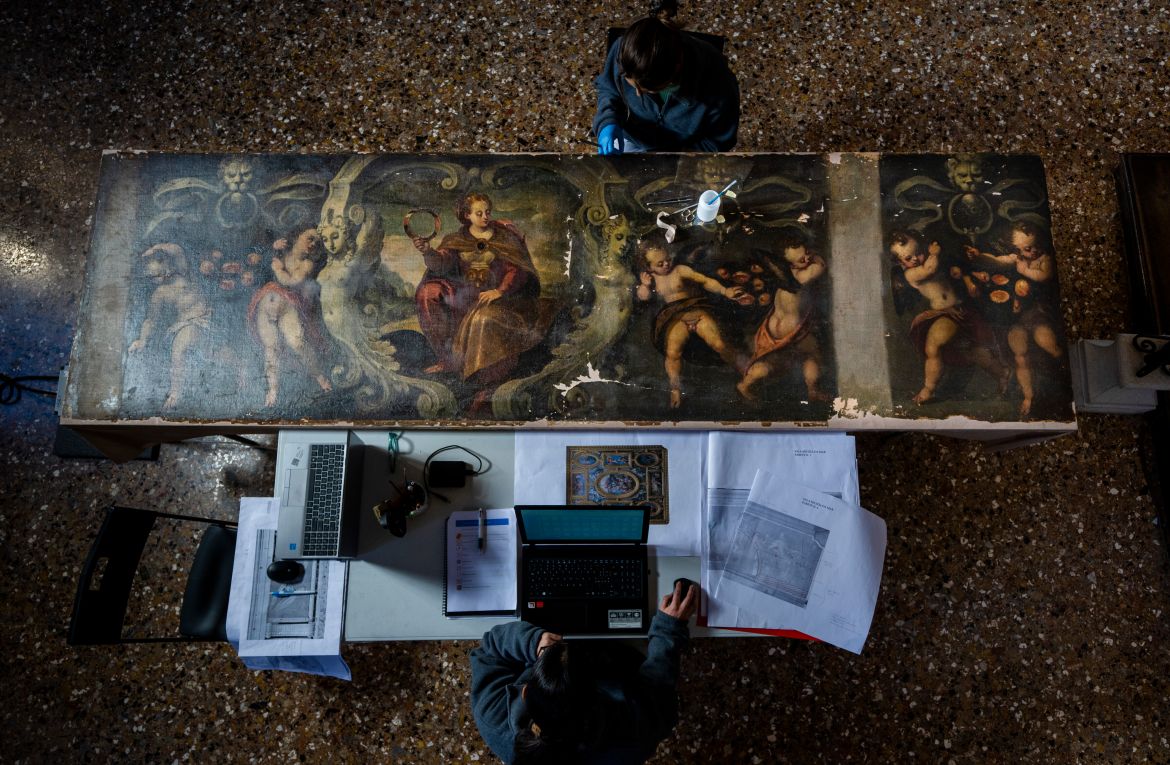

Art restorers intervene on precious artworks and elaborate ornamentation at the Doge’s Palace in Venice.

Art restorers in Venice are conducting an ambitious monitoring project to analyse and intervene early on precious artworks and elaborate ornamentation at a landmark Venetian palace that was at the heart of political life in the powerful maritime Republic of Venice.

The project at the Doge’s Palace, handled by the Fondazione Musei Civici of Venice, began in June and will last 14 months as restorers examine every centimetre of the surfaces of the palace — known as Palazzo Ducale — which contains some of the world’s most magnificent artworks, including paintings by Tintoretto and Titian.

The Italian government has provided 500,000 euros ($530,000) in funding for the project.

Using mobile scaffolding, so they can work on small portions at a time and leave the space open to visitors, restorers climb back and forth every day up a series of ladders to the ceilings where their tools include soft brushes and syringes.

In the Chamber of the Great Council, one of the largest paintings in the world, Tintoretto’s “Il Paradiso” at roughly 150 square metres (1,600 square feet), restorer Alberto Marcon is mapping out the surface centimetre by centimetre, noting the decayed parts that will require intervention or restoration.

The information will later go into a database that will help the team decide not only where they need to intervene with small operations or where a larger conservation effort is required, but also to monitor the artwork’s conservation status over time.

On the other side of the chamber, another restorer works on an elaborate frieze around the ceiling, dusting off the painting, looking for peeling paint and decay. In the nearby Hall of Ten, a restorer is carefully injecting glue into the gold-painted wooden ornamentation to protect it from decay.

Director of the project, architect Arianna Abbate, explains an effort that makes art monitoring a top priority, giving it considerable time and funds, is almost unheard of. Such “preventive conservation” might be “the new frontier of conservation”, she says as she stands on the scaffolding next to “Il Paradiso”.

Abbate says their primary work is visual and tactile, but it also includes monitoring with magneto-material, endoscopic, photographic and multispectral techniques.

In some cases, the decay is so severe they need to intervene immediately, so the team has set up a temporary studio in the Doge’s private chapel where restorers can work on the individual paintings.

Once the entire job is complete, other groups, such as the US nonprofit Save Venice, will step in to help fund further restoration deemed necessary.

The humidity and saltwater in Venice, a 1,600-year-old city built on a lagoon with its ancient palaces connected by canals, is particularly hard on architecture and artworks. The Doge’s Palace is located at the edge of St Mark’s Square facing the lagoon with a canal running down the side.