In Pictures

‘People of the Water’ try to survive loss of lake in Bolivia

Lake Poopo dried up in 2015 – it used to sustain the livelihoods and culture of the Indigenous community around it.

For many generations, the homeland of the Uru people here was not land at all: it was the brackish waters of Lake Poopo.

The Uru — “people of the water” — would build a sort of family island of reeds when they married and would survive on what they could harvest from the broad, shallow lake in the highlands of southwestern Bolivia.

“They collected eggs, fished, hunted flamingos and birds. When they fell in love, the couple built their own raft,” said Abdón Choque, leader of Punaca, a town of some 180 people.

Now what was Bolivia’s second-largest lake is gone. It dried up about five years ago, a victim of shrinking glaciers, water diversions for farming and contamination. Ponds reappear in places during the rainy season. The body of the lake, 3,700 metres (12,139 feet) above sea level used to cover an area of 1,000 square kilometres (390 square miles) and at its highest level in 1986, had an area of 3,500sq km (1,351sq miles).

The Uru of Lake Poopo are left clinging to its salt-crusted former shoreline in three small settlements, 635 people scrabbling for ways to make a living and struggling to save even their culture.

“Our grandfathers thought the lake would last all their lives, and now my people are near extinction because our source of life has been lost,” said Luis Valero, leader of the Uru communities around the lake.

Not long before the lake was lost, the language of the Uru-Cholo had perished as well. The last native speakers gradually died and younger generations grew up schooled in Spanish and working in other, more common Indigenous languages, Aymara and Quechua.

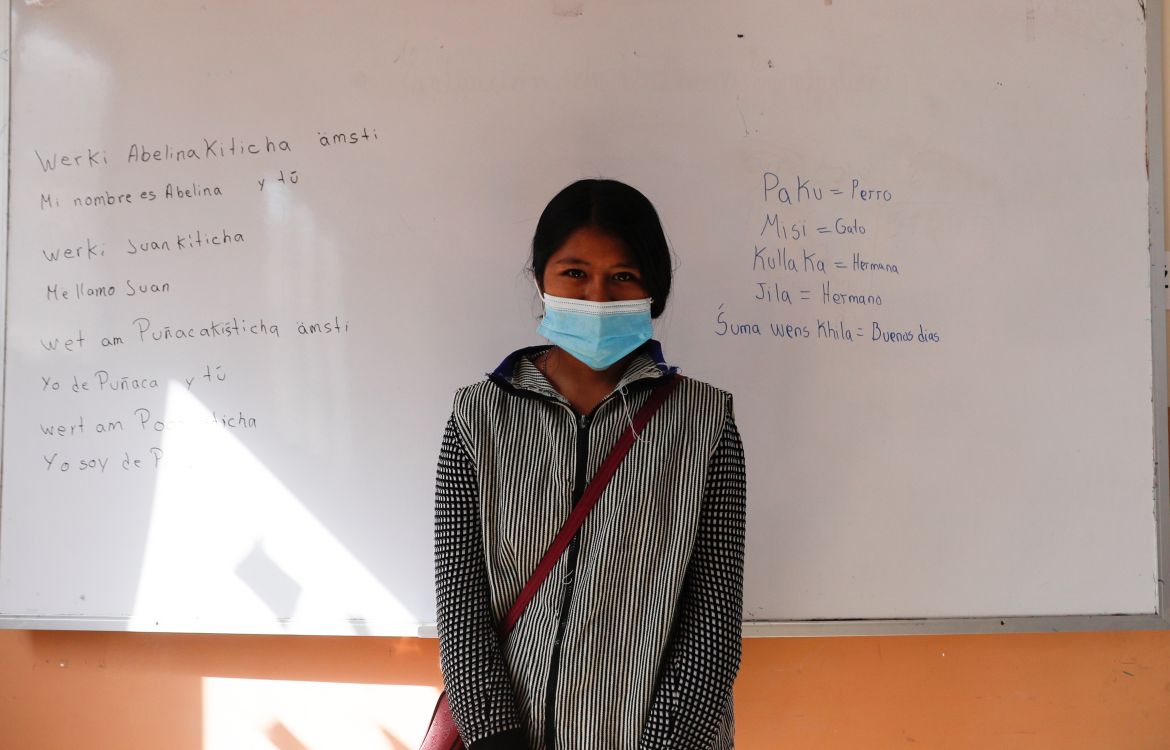

To save their identities, the communities are trying to revive their native language — or at least its closest sibling. Aided by the government and a local foundation, they have invited teachers from a related branch of the Uru, the Uru-Chipaya near the Chilean border to the west, to teach that tongue — one of 36 officially recognised Bolivian languages — to their children.

“In this times, everything changes. But we are making efforts to maintain our culture,” Valero said. “Our children have to recover the language to distinguish us from our neighbours.”

“The instructors teach us the language with numbers, songs and greetings,” said Avelina Choque, a 21-year-old student who said she one day would like to teach mathematics. “It’s a little difficult to pronounce.”

The pandemic has added to that struggle. The teachers have been unable to hold in-person classes during the pandemic, leaving students to learn from texts, videos and radio programmes.

Punaca Mayor Rufino Choque said the Uru began settling on the lakeshore several decades ago as the lake began to shrink, though by then, most of the lands around them had been occupied.

“We are ancient [as a people], but we have no territory. Now we have no source of work, nothing,” said the 61-year-old mayor, whose town consists of a ribbon of round, plastered block homes along an earthen street.

With no land for farming, the young men hire themselves out as labourers, herders or miners in nearby towns or more distant cities. “They see the money and they don’t return,” said Abdón. Some of the women make handicrafts of straw.

The broader Uru people once dominated a large swath of the region, and branches remain around Peru and Lake Titicaca to the north, around the Chilean border and near the Argentinian border.