In Pictures

In Pictures: How India’s lockdowns ruined Kashmir’s economy

Kashmir’s economy is yet to recover from a colossal loss a year after New Delhi scrapped the region’s autonomous status.

A year ago, Abdul Rashid was making a living by selling flowers to tourists in hundreds of ornate pinewood houseboats on Dal Lake in Srinagar, the main city in Indian-administered Kashmir.

When India suddenly scrapped disputed Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status, followed by an unprecedented security clampdown, economic ruin ensued.

“It was not just a political change. It destroyed our livelihood,” said Rashid, 60, who has now turned to growing vegetables to feed his family.

Days before the August 5, 2019, decision by India’s central government, authorities asked hundreds of thousands of tourists, Hindu pilgrims and migrant workers to leave the territory, shutting its economy. Since then, tens of thousands of jobs have been lost.

The stunning Himalayan region in parts ruled by India and its western neighbour Pakistan since 1947, when British colonial rule ended with the creation of India and Pakistan. A portion of the region, Aksai Chin, is under Chinese control.

An armed rebellion erupted in 1989 after decades of political manipulation in Indian-administered Kashmir, broken promises and a crackdown on dissent by New Delhi.

Kashmiri rebels, who enjoy popular support, seek unification with Pakistan or complete independence. India dubbed the armed rebellion “terrorism” abetted by Pakistan, a charge Islamabad denies.

Hundreds of the colourful hand-carved houseboats, known as shikaras, lie deserted, anchored still on the desolate lake. Hotels are empty, and there are barely any tourists.

Some businesses had resumed with the partial lifting of the security and communication clampdown earlier this year. However, Indian authorities enforced another harsh lockdown in March to combat the coronavirus pandemic, further emaciating the local economy.

The Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industries pegged the economic losses in the region at $5.3bn and said about half a million jobs had been lost since August last year.

The seven-decade-old Hotel Standard in Srinagar had a staff of 30, according to its manager Khurshid Ahmed. Now there are just three. The only activity inside the once-bustling place is that of the cleaning staff.

Mohammed Rajab, a taxi driver for 37 years, has not received on fare since last August. “I parked my taxi at our stand a few days before August 5 last year. It’s still there, along with 250 others,” he said.

Tens of thousands of daily wage workers, like Rajab, have suffered the most.

Mohammad Lateef, a boatman, used to ferry tourists around the lake. He now sells cucumbers and cigarettes to locals along its banks.

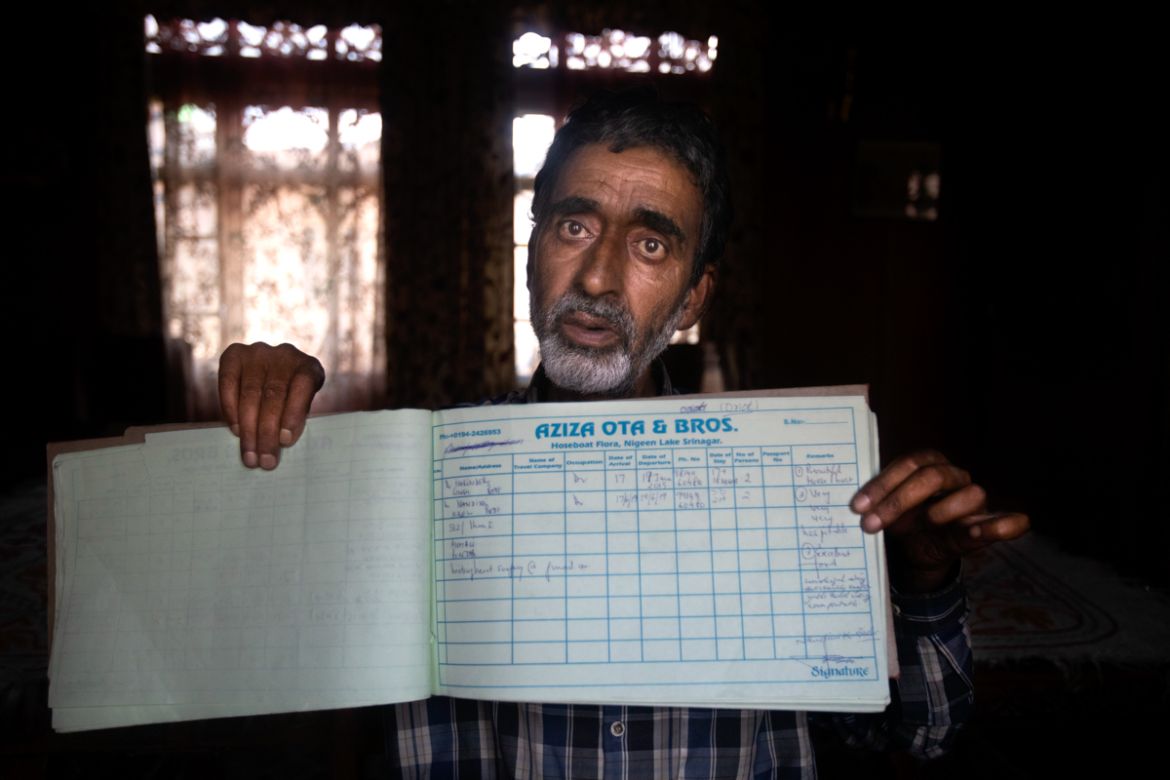

“We’ve not earned a single penny for a year now,” said Ghulam Qadir Ota, a houseboat owner. “All we have are these boats. We don’t have any other means to earn.”