In Pictures

Rosia Montana: Seeds of utopia in town almost lost to gold mining

Hope and unease in fertile Romanian village, six years after protests halted plans for Europe’s largest gold mine.

Transylvania, Romania – In 2013, Rosia Montana was almost destroyed to make way for a gold mine – plans that continue to haunt the village which sits in the Apuseni Mountains of western Transylvania.

Six years ago, Gabriel Resources, a Canadian company, came close to destroying “red mountain” to build Europe’s largest gold mine.

Tens of thousands of people protested weekly for months in a row to defend the commune, eventually forcing the government halt plans to build the mine, but the company did not give up.

In 2015, it sued Romania before of the ICSID, the World Bank arbitration court, asking for a reported four billion dollars in damages.

At the time, Gabriel Resources had already purchased much property in the village; only those determined to fight until the end stayed.

While the arbitration case advanced out of public sight in Washington, new people started moving into Rosia.

Activists, architects, artists and free spirits can now be found here creating a new kind of community, one based on neighbourly cooperation.

In 2017, riding the wave of public sympathy for Rosia Montana, a technocratic government submitted an application to UNESCO to make it a World Heritage Site. The village has a history of two millennia and it hosts Roman mining galleries and architecture spanning centuries.

Even as UNESCO indicated the village was likely to get international protection, Romania’s new Social-Democratic government withdrew the application in 2018.

Activists feared this meant Romania was gearing up to cut a deal with the company.

Today, Rosia Montana is in limbo.

People who want to renovate buildings or start businesses say they struggle to get permits as the mine might still go ahead.

Yet the local community is flourishing.

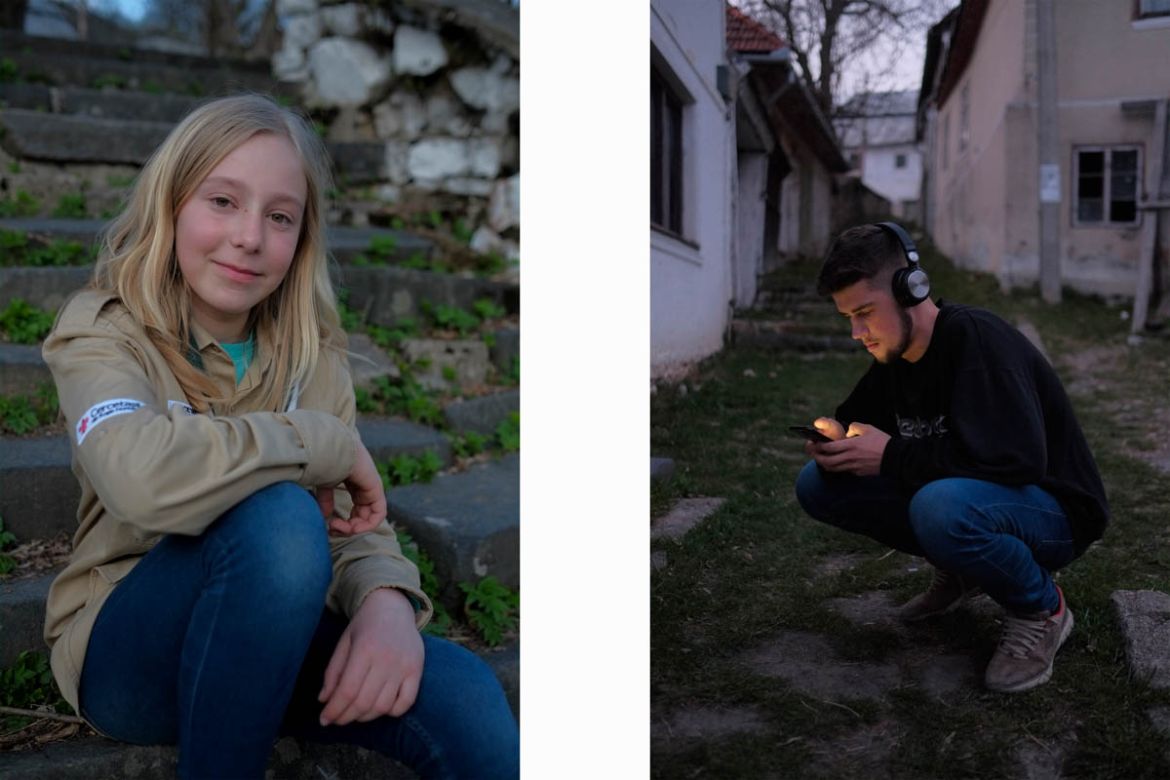

Fashionable youngsters, bikers and herbal medicine aficionados co-exist alongside retired miners, village priests and peasants, in a throwback to the multiethnic, multi-faith past of Rosia Montana.

This motley society has its shared myths, forged in the years battling the mining plan, and a common vision for the future.

Rosia has a strong international brand, they say, and the village is ready for reconstruction.

Corina Suteu, Romania’s former minister of culture, said missing out on the UNESCO stamp could hinder restructuring efforts and hold the area back from becoming a rich tourist hub and ecological site.

Earlier this year, in a move that has alarmed the local community and activists, the Romanian government proposed a draft mining law which would make it easy to grant new permits for the mine previously denied by national authorities or courts.

“The new law is a confirmation and a first physical step towards a settlement and the still possible go-ahead for the mine,” said Stephanie Roth, an activist who received the Goldman Environmental Prize for campaigning against the mine.

Suteu added: “What is certain is that this region continues to be protected by national law.

“Any attempts to reverse this protection are not in line with the national interest and a public agenda of protecting patrimony.”