In Pictures

The slow road to recovery for rape survivors in the DRC

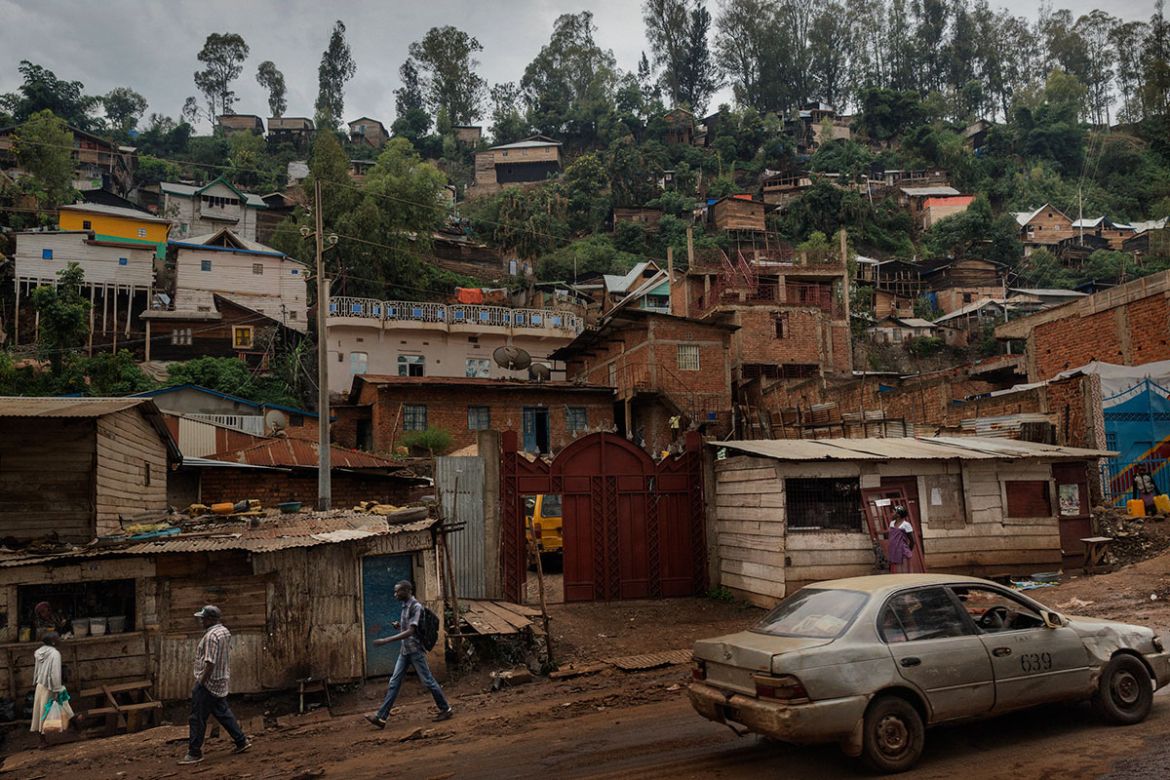

In eastern DRC, an outpost of hope provides medical, psychological and social help to marginalised victims.

North and South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) – During the “Second Congo War”, which began in 1998 in eastern DRC, sexual violence was used systematically as a weapon of war.

The hostilities officially ended in 2003, but the region remains unstable owing to external influences, ingrained ethnic divisions and the fight over the country’s mineral wealth. Eastern DRC continues to be plagued by armed groups. Since 1998, more than five million people are estimated to have died as a result of the conflict, disease and poverty.

The DRC has long been exploited for its resources, from colonial times under King Leopold II of Belgium, and today by US, Chinese and European companies. The land is rich in raw materials such as rubber, ivory, gold, diamonds, uranium, coltan and timber. In return, it has suffered from war, corruption, death, disease, hunger, mercenaries, child soldiers and rape. Rape, sexual violence, and the abuse of women is the tragedy within the tragedy here.

Over nine months in 2014, the United Nations Population Fund recorded nearly 12,000 cases of gender and sexual-based violence in five eastern DRC provinces; 39 percent of cases were considered to be directly connected to armed conflict. A 2010 study found that four women are raped every five minutes.

“My friends avoid me because they think that, if they remain friends with me, I could lead them astray because I have jeopardised my future,” says Ombeni, 13, who was raped by a member of the local parish. “They make fun of me continuously, saying that a person who does not live with either their mother or father will ruin their future. They do not allow me to get close to them.”

Rape victims are not only traumatised; they are often abandoned and marginalised by their communities. But Ombeni’s mother has remained supportive of her daughter.

“Every time I look at my daughter and see her contemporaries that go to school what comes to my mind is what happened to her. So thus I pray to God. I pray that the one who raped her will have a daughter and she could have the same tragedy, so that he could understand what it means,” she says.

Vumilia Elisabeth, 53, was raped by members of the Rwandan Hutu rebel group, the FDLR. “My community found out about what happened and now they constantly make fun of me and everyone speaks badly about us and considers us to be worthless,” she says. “People consider us to be worthless and we are called ‘the raped’. This is very shameful and we no longer see ourselves as human beings.”

Panzi Hospital, founded in 1999 in Bukavu, in eastern DRC, is one of few outposts of hope for survivors. It provides psychological help, treats complex gynaecological injuries and helps reintegrate the girls and women into their societies. They see between 1,300 and 1,900 patients a year.

Zawada Bagaya Bazilianne, a legal counsel from Panzi, says in the village of Kavumu, 30km from Bukavu, 44 girls ranging in age from two to 11 years old were raped by armed men between 2013 to 2016.

The suspects, 74 paramilitary soldiers from a personal militia of the provincial deputy Frederic Batumike, are incarcerated in Bukavu. Investigations found that the rapes were committed as a black magic ritual to obtain invincibility in battle, find gold and cure HIV infections. These are not isolated cases. The accused have been charged with rape and crimes against humanity.

“The real problem is the impunity,” says Dr Denis Mukwege, a 2014 Sakharov Prize laureate and the founder of Panzi Hospital.

“The fact that [those] who commit these acts go unpunished, all this makes these people think they can continue to rape,” Mukwege says. “To solve this problem and [to fight] its roots we have to denounce it nationally and internationally, because what happens is closely related to the illegal Congo’s minerals exploitation and plundering, especially the coltan.”