In Pictures

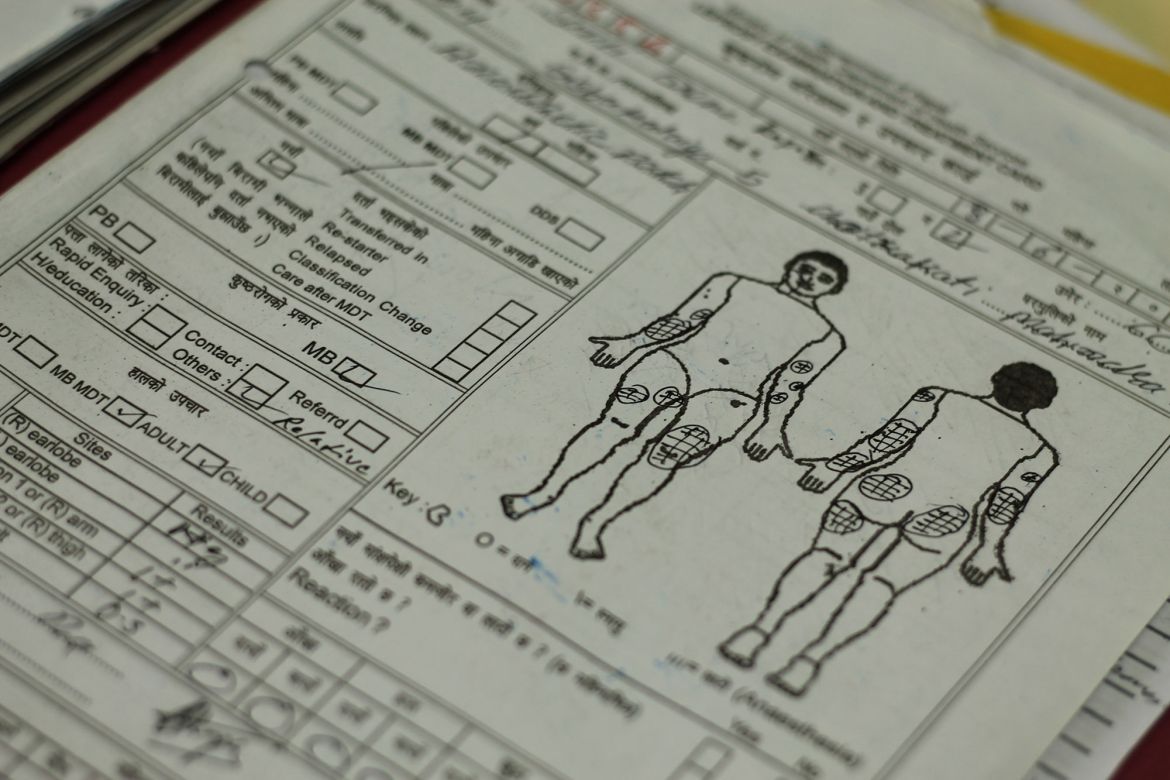

Inside Nepal’s busiest leprosy hospital

The Lalgadh clinic aims to treat, rehabilitate and provide psychological counselling, but patients often come too late.

Lalgadh, Nepal – The Lalgadh Leprosy Hospital in Nepal is considered one of the busiest in the world, with more than 1,200 new patients each year.

Founded by a British nurse, Eileen Lodge, in 1993, the hospital originally had just three staff members. Now the medical team is 34-people strong.

Each year, about 250,000 people are infected with leprosy worldwide. Although Nepal’s government announced that leprosy had been eliminated in the country in 2009 – based on the World Health Organization’s measurement of less than one case per 10,000 members of the population – that does not mean it has been eradicated. In fact, leprosy is endemic in some parts of the Himalayan country.

Despite the very low risk of infection, the stigma surrounding the disease can be extreme in Nepal. Patients are often isolated and abandoned by their families and communities in a country where the law prohibits infected people from working or marrying. In some rural areas, the disease is considered a curse from God as a punishment for sins committed in a former life.