Child soldiers used in Yemen war

Human rights groups say both sides in the conflict have been recruiting teenagers.

|

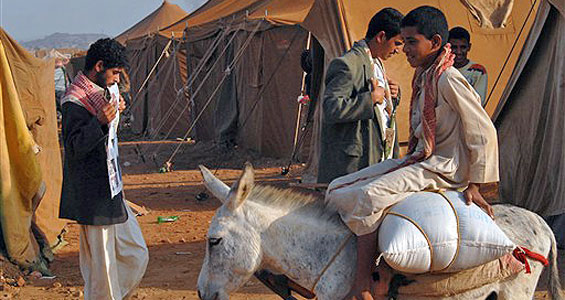

| Rights organisations accuse the Houthis of using children to recruit other children [AFP] |

At first, it is difficult to see the boy sitting behind the rows of microphones, spotlights shining down on him as cameras roll from all sides of the packed hotel conference room.

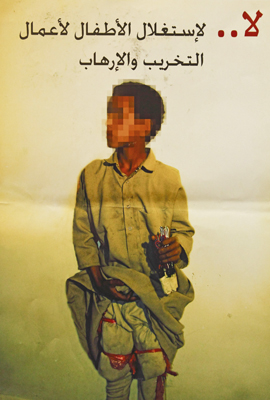

Above the table where Akram sits hangs a huge poster showing a Yemeni boy dressed in a traditional brown robe, holding a detonator in one hand, while with the other he lifts his gown to reveal packages strapped to his legs.

The Arabic reads: “No to the exploitation of children for destructive operations and terrorism.”

Prior to the press conference a text message from the government had alerted journalists and aid workers to the shocking news: A nine-year-old suicide bomber had been arrested carrying a bomb through the Old City of Saada, the north Yemen region that has served as the stronghold of the powerful Houthi clan.

The clan has for the past five years led an armed rebellion against the government in the capital Sanaa.

Strapped up with explosives around his legs and a detonator in his hand, the photograph appeared to embody the cruelty of the increasingly bitter war, a child made into a bomb by rebels who would stop at nothing to inflict casualties and terror.

Propaganda?

|

| A government poster depicting Akram wearing explosives and holding a detonator [Flamand] |

The government said Akram had been stopped by police in Saada before he could reach his target. At the police station the boy was photographed and the media was called in to report on the young would-be suicide bomber.

Akram and his father were then driven to Sanaa to tell their story to the assembled crowd of Yemeni officials, children’s rights groups and journalists.

Standing, Akram takes a microphone in his small hand and delivers his message: “To use children in war is wrong.”

A day after the press conference, Akram’s father told Al Jazeera that his son never carried explosives. “Bomb? There was never any bomb. There were thirty detonators, but no explosives,” he said.

Akram said he was asked by a distant cousin to deliver a package of wires to a friend in Saada’s Old City. “He said, ‘This is just wires.’ He tied the bags to my legs and put something in my pocket,” said Akram.

One local NGO worker, speaking anonymously for fear of reprisal, told Al Jazeera that he had been contacted by the government who asked if he would talk to Akram and persuade him to confess to being a suicide bomber.

“I knew immediately the poster was a fake,” he said. “The children need help, not this. We are independent and will not get involved in government propaganda.”

Children in conflict

Whatever the truth about what Akram was carrying, his exploitation as a child soldier in Yemen is far from unique. A culture of under 18s carrying arms is ingrained in Yemen’s tribal society.

Rights groups estimate that several thousand child soldiers have been involved in armed combat.

“We have a saying here,” said Ahmed al-Gorashi, the chairman of Seyaj, a local NGO working to prevent the use of child soldiers. “If you are old enough to carry the jambiya [a curved dagger traditionally worn in the belt of Yemeni men] then you are old enough to fight with your tribe. And children carry the jambiya from the age of 12.”

Across Yemen’s countryside, it is a common site to see boys of 13 or 14 years old carrying Kalashnikovs as they ride with members of their tribe in the back of pick-up trucks.

The government accuses the Houthi rebels of using children as soldiers and of recruiting young boys from schools in Saada into their ‘Believing Youth’ movement.

“The Houthis use children to recruit other children from schools. They send the children leaflets and books to read saying joining Believing Youth is a way to become closer to God,” said Mariam al Shwafi, the manager of Shawthab, a local children’s rights organisation.

Although the official minimum age for joining the army is 18, the tribes which the government arms and finances to fight the Houthis alongside the army also often use children.

“The government is not knowingly recruiting underage soldiers into the army, but the tribal militias they are signing up are using child soldiers,” said Andrew Moore, the country director of Save the Children in Yemen. “It’s a deep cultural issue, but if we don’t talk about it, it’s never going to change.”

UN investigating

| in depth | |||||||||||||||||

|

No accurate figures exist for the number of children being used as soldiers in Yemen.

In a country of 25 million people, there are believed to be up to 60 million guns.

Abdul-Rahman al-Marwani, the chairman of the Dar as-Salaam Organisation to Combat Revenge and Violence, a local NGO, reports that as many as 500 to 600 children are killed or injured through direct involvement in tribal combat in Yemen every year.

Seyaj estimates that under 18s may make up more than half the fighting force of tribes, both those fighting with the Houthis and those allied with the government.

The problem of child soldiers in Yemen is now grabbing the attention of the international community and Unicef, the UN’s children’s rights agency, has been tasked with reporting on the issue.

Radhika Coomaraswamy, the UN’s special representative of the secretary-general on ‘Children and Armed Conflict’, said she is extremely concerned that “large numbers” of teenage boys have been dragged into the fighting.

Yemen is a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child and ratified in 2007 both its optional protocols which “require states to do everything they can to prevent individuals under the age of 18 from taking direct part in hostilities”.

Persistent failure to prevent children taking part in conflict is considered a war crime by prosecutors at the International Criminal Court.

Retaliation

The day after his name and face appeared on Yemeni TV, Akram’s house in Saada’s Old City was targeted by a bomb. Retaliation, so the government said, by the Houthis. Akram’s younger brother was at home when the explosion struck and pieces of shrapnel shot into his face and chest.

At the time of our interview, the boy had yet to receive surgery for his injuries and was being cared for by his grandmother, Akram’s mother having died last year, while his father had been driven to Sanaa with government officials before he could return home to help.

Though furious with the cousin who used his son as a child soldier, Akram’s father said the hurt had been compounded by the government’s effort to turn the story into a propaganda campaign.

“The government has put our family in a bad situation. I am too scared to go back to Saada now,” he said. “We feel used.”

As for Akram, like so many child soldiers manipulated at the hands of adults, he appears to understand little of who or what he was supposed to be fighting for. But as to the consequences of the conflict he has been caught up in, Akram is only too painfully aware.

“I miss my grandmother and I’m worried about my brother,” Akram said.

“I’m not together with all my family and I want to see them again, but I can’t because of this war.”