Saving Sarah: The last Jewish embroidery shop in Kochi

How one Muslim man's deep bond with a Jewish woman in India lives on through the shop she left to him.

Kochi, India - A chance encounter when he was selling postcards to tourists in Jew Town as a 13-year-old in the early 1980s would change the course of Thaha Ibrahim’s life.

Growing up in Mattancherry, a bustling hub of the spice trade in the southern Indian city of Cochin (now Kochi), Thaha Ibrahim had always found the world outside far more captivating than the confines of his classroom.

So when he left school in the sixth grade, his family did not try to stop him. He explored different trades, from assisting his father, a tailor, with stitching clothes to helping his uncle in the spice business. But, mostly, he was drawn to the tourists who arrived in droves on the ships that docked in the port.

Invariably, they would flock to see the centuries-old Paradesi Synagogue in Jew Town, the neighbourhood in Fort Kochi, a busy, touristy waterfront area of Kochi that had once been used by Portuguese, Dutch and British merchants during colonial rule of the city.

Thaha would arrive in the morning in Jew Town, spend the day selling postcards on the street to tourists visiting the synagogue and return home at dusk. As an Indian Muslim, he always maintained a respectful distance from others in the Jewish neighbourhood.

That all changed one Sunday in 1982 when, as a ship packed with Western tourists docked, bringing the promise of postcard sales, Thaha faced an unexpected obstacle.

His usual storage space - a small warehouse on the waterfront known as a “godown” whose owner allowed him to stash his postcards there each evening - had been locked up by the watchman. He waited under the burning sun from 8 in the morning until 1 in the afternoon, but nobody came to unlock it.

It was at this point that Jacob Elias Cohen, a resident of Jew Town and a member of the Paradesi Jewish community, happened to be passing by the godown and noticed Thaha.

He recognised the boy whom he had seen selling postcards outside his home and, moved by the teenage vendor's plight, decided to try to help. “Come to my house after your sales tomorrow,” he told Thaha. “You can store your things at my place.”

Memories from inside Sarah’s shop

Thaha’s first encounter with Jacob’s wife, Sarah, at the couple’s home the following evening did not go quite as well. The boy had seen Sarah around the neighbourhood before, sometimes buying produce from the vegetable vendors who hung around the same spots he himself did, but he had never spoken to her. She had not yet opened her embroidery shop in the neighbourhood but was known for her sewing skills, stitching clothes for friends and neighbours with the help of three servants who worked for the couple.

Today, Thaha, now 54, recounts his memories of Sarah inside the shop, Sarah’s Hand Embroidery, as he stands among its range of Jewish accessories, souvenirs and handicrafts - menorahs, table linen, placemats, towels, kippas and challah covers.

The entrance to the shop is adorned with the words "Sarah Cohen's Home" in elegant calligraphy and the Star of David. Next to it, a steel plaque reads, "Sarah's Hand Embroidery," and features a photo of Sarah Cohen immersed in her work.

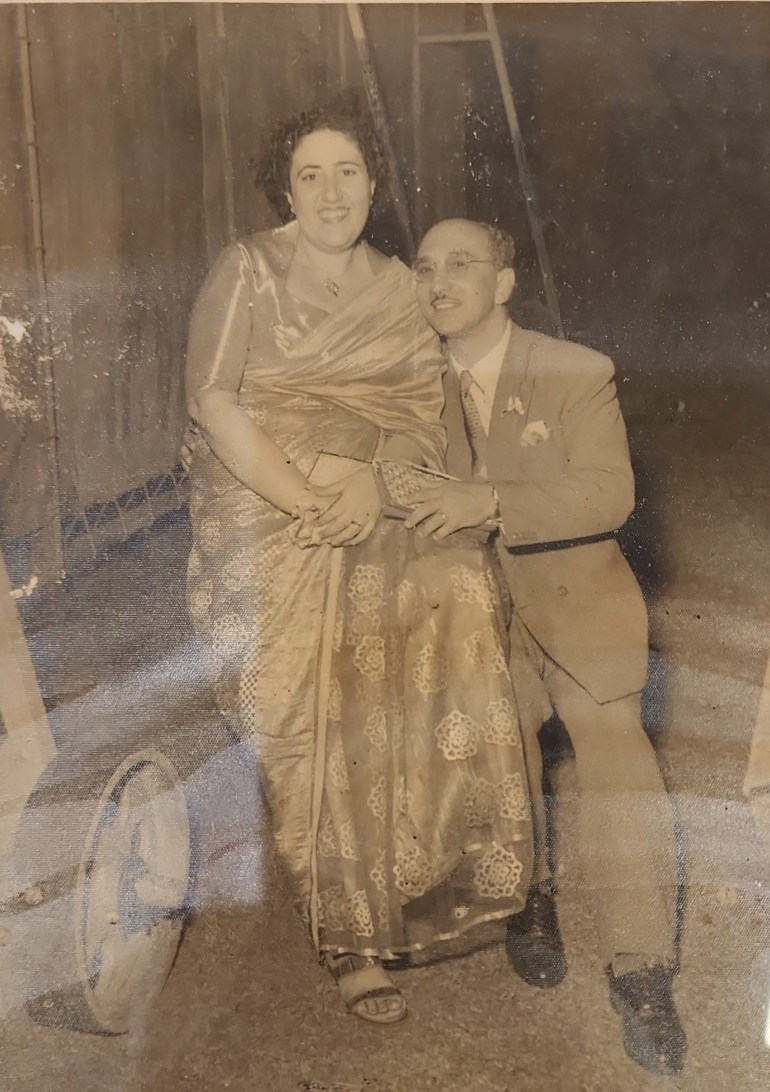

The walls of the shop are adorned with black and white photos that chronicle the Cohens' life journeys: from the youthful vibrancy of Jacob and Sarah through their wedding to their later years, including a meeting with Britain's then-Prince Charles and a nostalgic snapshot of Sarah in her shop.

"Jacob Uncle and Sarah Aunty were a love-married couple. They always shared the same views - except when it came to me," Thaha says, reflecting on his first meeting with Sarah, when he visited their home following Jacob's suggestion.

When she had asked sharply what he was doing there back in 1982, the 13-year-old had replied hopefully: "Jacob Uncle suggested I store my board and postcards here."

Thaha now recalls how the atmosphere suddenly grew tense as Sarah, visibly displeased, called her husband. Jacob was quick to shrug off her annoyance: “He's just a boy, Sarah. Let him keep his things here."

What unfolded next was an incomprehensible drama for Thaha. The couple, who usually spoke in Malayalam, shifted their argument to English to hide their disagreement from him.

Thaha says now that in that moment he wished for nothing more than to vanish from the escalating tension as his initial hope turned into discomfort.

"I'll leave, no problem,” he protested. “I can store my things in the godown."

Jacob's reply was swift and decisive. "If you take your things now, don't bother coming back to Jew Town for sales."

Hearing this, Sarah retreated to the kitchen, bristling with disapproval over the arrangement her husband had made.

Little did any of them know, however, that this sparky start was just the beginning of a deep bond between Thaha and Sarah, which would survive beyond her life and keep her legacy - Sarah’s Hand Embroidery shop, today the last Jewish embroidery shop in Kochi - alive.

The ‘first emporium of India’

Sarah and Thaha’s near 40-year bond was one between two unlikely friends - a Muslim boy and an elderly Jewish woman from different social classes.

"Initially, my journey to document Sarah Aunty and Thaha Ikka was driven by an interest in their interfaith dynamic," says Sarath Kottikkal, the director of a documentary called Sarah Thaha Thoufeeq about the pair’s relationship, which he documented from 2013 until Sarah’s death in 2019. "But as I spent more time with them over the years, it became clear that the religious difference was for outsiders. Between them, it was like a son caring for his mother."

It was certainly outside the norms for the Muslim and Jewish communities of Kochi, which traditionally did not mingle much.

Kerala's first Jewish settlements date as far back as ancient Israel and the reign of King Solomon, believed to have lasted from 970 to 931 BC. They are linked with trade on southwest India's Malabar Coast, the “first emporium of India”.

A second wave of Jewish settlers, Sephardic Jews fleeing Spanish persecution, arrived in Cochin in 1492, journeying via Portugal, Turkey and Baghdad.

These newcomers, known as Paradesi (“foreign”) Jews, joined the initial settlers, the Malabari Jews, who had first settled on the Malabar Coast, to form the community of Cochin Jews - now one of the oldest Jewish communities in India.

They spoke Malayalam like the locals and used Judeo-Malayalam, a language that combines Hebrew, Aramaic and Malayalam, in their hymns but strictly adhered to their religious traditions.

The Cochin king granted land to the Paradesi Jews near the Malabari Jews in Mattancherry, where they built the Paradesi Synagogue in 1568. Eventually, Jew Town Road, the street extending from Mattancherry Palace to the Paradesi Synagogue, became an enclave of the Jewish community predominantly inhabited by Paradesi Jews.

Centuries later, the formation of the State of Israel in 1948 marked a turning point for the Cochin Jews, initiating a gradual exodus from 1952 onwards to Israel. The Jewish community in Jew Town, which numbered about 250 in the late 1940s, was reduced to under 30 when Thaha came there.

Among those who decided to stay behind were the Cohens, both of whom had been born and raised in Jew Town and married in 1942. The couple had no children, and with their ancestors resting in Cochin soil, they found no reason to leave the place where they were emotionally rooted. "I won't leave India. This is my home," Sarah would say.

‘So you know about stitching!’

In the early days of Thaha’s friendship with the Cohens, he remembers a busy household with three servants. Jacob, then in his early 70s, was semiretired and continued working as a private tax consultant. Sarah, in her early 60s, had become the go-to tailor in Jew Town and was a master of traditional Jewish embroidery.

Initially, Thaha served as Jacob's helping hand, using a bicycle to quickly fetch photocopies and other things Jacob needed for his work, while Jacob rewarded him with pocket money. "Whenever I watched cricket through the Cohens’ window, he would invite me inside and give me a seat," Thaha recalls of his beloved "Dicky Uncle".

But one day, as Thaha, now aged about 19, was making his usual postcard sales in Jew Town, Sarah broke the ice between them and approached him for assistance as well.

She was in need of his father’s tailoring skills to help with stitching a cushion cover for the synagogue. His father had stopped sewing due to age-related issues, so Thaha offered to help instead. Unaware of the skills Thaha had himself picked up from working with his father, Sarah was hesitant, but when she saw the pattern he had made for the cushion, she was delighted.

"So you know about stitching!" Sarah said, surprised at the accuracy of his work, a task she said her own assistant had failed to master. "From then, Sarah Aunty started having a fondness towards me," Thaha recalls.

By this time, it was the late 1980s, and Sarah had opened her shop, Sarah’s Hand Embroidery, in her living room.

From there, she sold kippas (traditional Jewish skullcaps) and challah covers (to cover bread).

Thaha reminisces about the “excitement and anxiety” he felt the day she first allowed him to use her cherished Singer sewing machine, a gift from Jacob in the 1940s when buying such a machine was like purchasing a car.

Thaha became proficient at stitching kippas and traditional Jewish crafts, learning from Sarah while helping her in his spare time away from his postcard sales.

Thaha had initially considered stitching a trivial skill, but his perspective shifted as he cultivated a passion for it through Sarah's mentorship. She playfully chided him for being "a very good tailor, but a lazy one".

By the 1990s, Jew Town's Jewish population had fallen below 20 while tourism surged along with demand for Sarah’s products. She began outsourcing production to local stitching units using her designs with Thaha handling the logistics. "Sarah Aunty used to give me an amount from the profit," Thaha says.

Before he died in 1999, Jacob, facing the reality of his declining health, entrusted Thaha, by now married with children of his own, with a significant request: "Sarah has no one. You must be there for her."

Thaha, understanding the weight of this request, agreed with a condition: "I am happy to look after Sarah Aunty if she allows me." He elaborates on his conditional acceptance: "I specified 'if she allows me' because in our Muslim faith, failing to honour a dying wish once we've committed to it is a grave mistake."

Thaha and Sarah became family. "I have spent more time with Sarah Aunty than with my mother," says Thaha, who would arrive early in the morning and stay until the shop closed at night.

From buying household essentials to arranging for a woman to cook for her and keep her company at night after he left, Thaha made sure Sarah got the care and help she needed. Thaha also moved closer to Jew Town after Sarah's health declined.

In 2000, Sarah, then 77, asked Thaha to run the shop on her behalf. She gave him a clear directive: "The business should only grow from here, never decline. Take all the profits but also look after me."

And that is what he did. As well as running the shop, Thaha would bring her kosher meat and fish as long as it was available in Kochi and then would get her bread on Friday, so she could observe the Sabbath.

"Today, I continue to close the shop on Saturdays for Shabbat and on other Jewish holidays, just as Sarah Aunty did," Thaha says.

"Thaha was like a son to Sarah Aunty, and he cared for her like his own mother," a family friend of Sarah Cohen, who once lived in Kochi, says during a phone call from Israel, preferring to remain anonymous for this article.

Providing the parochet

The pair’s bond had spanned more than 36 years when Sarah died at the end of August 2019 at the age of 96.

She had yearned for a parochet, a long cloth with Jewish inscriptions and designs that is used in synagogues to cover the Torah after it has been used to cover a coffin. She wanted one stitched by Thaha himself to grace her coffin.

"I never liked to do it as she was alive," Thaha recalls. "But Sarah Aunty would tell me, crying, that she had no one else to tell this to."

This was not the only task she entrusted to him. She had long wished to be buried between her husband and her brother and instructed Thaha with the motherly authority she often adopted with him: "I want you to come and clean my grave as long as you are alive."

One scene from Sarath’s documentary is particularly poignant, the filmmaker says: "The scene where Sarah Aunty is willing to give her wedding ring to Thaha Ikka is enough to understand what he meant to Sarah Aunty."

In the scene, Sarah sits by her favourite window and struggles to reposition her wedding, momentarily confused due to her fading memory. Thaha puts the ring back on the ring finger of her left hand and says to her gently: "It belongs on this hand. Don't remove it, OK?"

He then reminds her of the ring's importance, evoking the memory of Jacob by reading the letters etched into the ring aloud, "C. O. H. E. N. Cohen."

Sarah, affectionately looking at Thaha, then remarks, "Poor, kind Thaha. You listen to whatever I say."

"What makes you call me ‘kind’ now?" Thaha asks.

"Don't you want this?" Sarah says, looking at the ring.

Thaha, somewhat taken aback, shakes his head no and says, "You wear it. OK?"

Sarah then looks out the window, her eyes welling up, prompting Thaha to ask: "Why are you crying now?"

"I don't need this because you love me," Sarah replies.

"You're showing love by offering me your gold ring?" Thaha, trying to mask his emotions, asks her in a playful tone.

And the scene ends there.

Upon her death, Sarah left her treasured possessions to Thaha: the wedding ring, her Singer sewing machine and her shop.

"Some things in life are beyond value," Thaha reflects. Today, the embroidery shop, which he continues to run, outsources stitching work to workshops beyond Kerala in the states of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, employing more than 100 women and staying true to Sarah's vision of growth.

The recent war in Gaza has not shaken his belief that bonds of love such as those he shared with the Cohens will endure.

"I don't view this war as Muslims versus Jews. It's clearly a political conflict where the leaders are weaponizing religion for their gain, creating division among people. This understanding should be enough to prevent us from hating individuals of other faiths. Religion should reside within us, but humanity must always take precedence," Thaha says.

Jew Town has evolved. Buildings once home to Jewish families are now antique shops, cafes and homestays. What used to be a private Jewish enclave is now a vibrant tourist destination. But one shop remains the same - Sarah's Hand Embroidery.

And while Sarah Cohen with her silver-white, bobbed hair, fibre-framed glasses, colourful maxi dress and matching kippa no longer graces the window from which she loved to watch the tourists, her legacy shines on through a Muslim man, Thaha, who insists it is still “Sarah Aunty’s shop”.