'Life's harder for the vulnerable'

Visually impaired and falling out of Ethiopia's middle class.

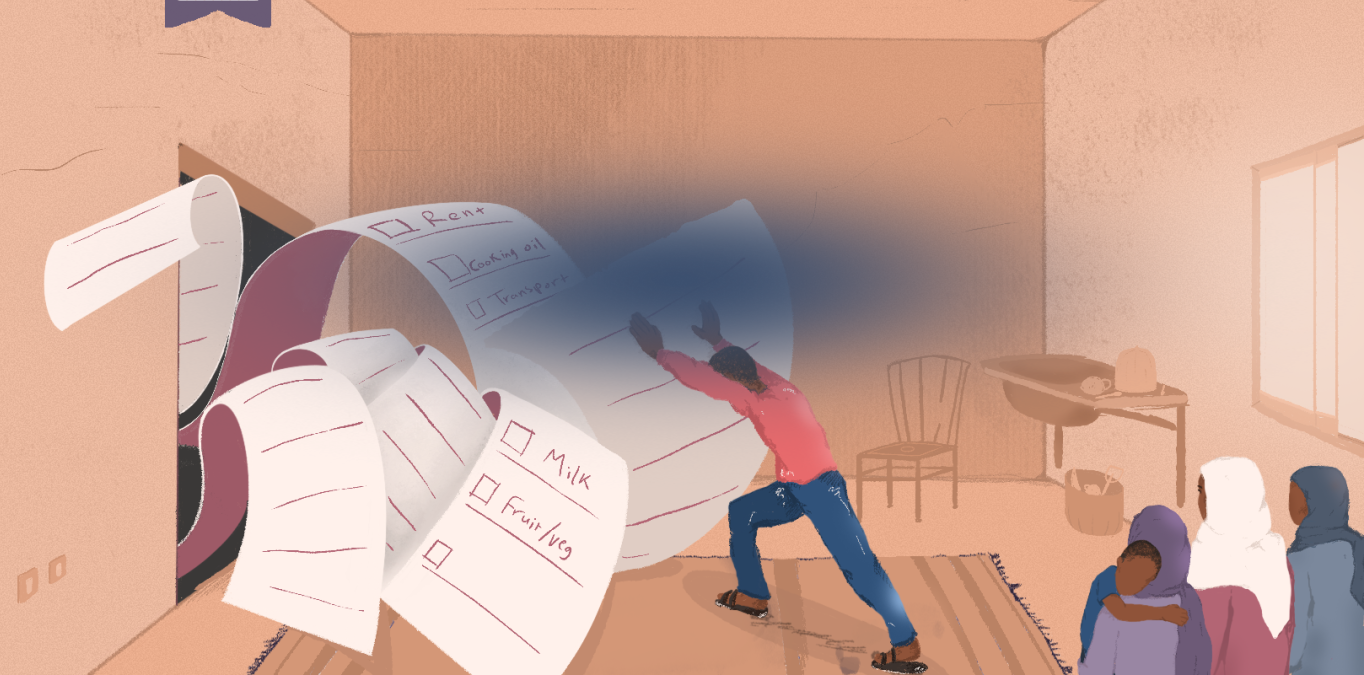

What's your money worth? A series from the front line of the cost of living crisis, where people who have been hit hard share their monthly expenses.

Name: Seid Anbesu

Age: 33

Occupation: Social worker in a government bureau

Lives with: Wife Jemila Muhammad (29), son Reyan Seid (2), sister Halima Bati (16), and domestic helper Aziza Shemsedin (16)

Lives in: A 38-square-metre studio apartment in Bole Arabsa on the outskirts of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital city. The studio consists of a single room that serves as both the living room and bedroom, separated by a curtain, with a bathroom and small kitchen attached.

Monthly household income: Seid earns a gross salary of 6,193 birr ($115), but after taxes and pension deductions, he takes home 4,770 birr ($88). His wife, also a social worker, earns 6,093 birr ($113), bringing the total household income to 10,809 birr ($200).

Total expenses for the month: 15,500 birr ($288)