The preacher's son who became a 'gangster romantic'

The story of Nigerian singer Lojay's journey from the church to celebrity status

Lagos, Nigeria - On the afternoon of July 4, the rapper Jay Z, one of the most recognisable people in the world, was driving to a Fourth of July party in New York. The speakers of the grey, open-air '90s Land Rover Defender were blasting Monalisa by the gap-toothed Nigerian singer-songwriter Lojay, one of the most recognisable songs in the world since 2021.

A short video of that scene travelled around the world within minutes, eliciting millions of "oohs" and "aahs", especially in Lagos by the next day.

Nigeria’s biggest city, where Lojay was born Lekan Osifeso Junior in April of 1996, remains Africa’s entertainment capital and home to Afrobeats, a genre that has dominated dancefloors worldwide over the last decade. But over the past four years, it has digested the electronic log drum sound of South Africa’s amapiano, an infectious house jazz hybrid.

Some of the results have been chaotic medleys but Monalisa is a distinctive example of the transcontinental amalgam, with its hypnotic melody and compelling emotive penmanship.

“His music doesn’t sound like anything out there,” Abiodun 'Bizzle' Osikoya, cofounder of Nigerian entertainment consultancy, The Plug, told Al Jazeera.

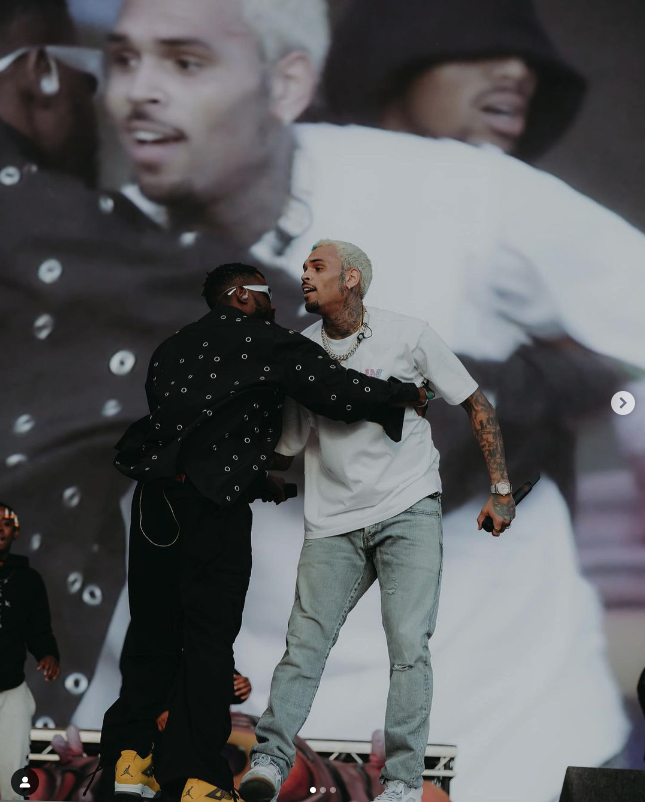

Since its release early in 2021 on LV N ATTN, the joint EP between Lojay and Grammy Award-winning producer Osabuohien "Sarz" Osaretin, the song has racked up wins on both sides of the Atlantic. That version and the remix with American superstar Chris Brown have permeated charts in dozens of countries and remain among the most searched-for songs on Shazam, the popular music-identifying app.

To many onlookers, the Jay Z-Monalisa moment this July further validated the widespread appeal of the song, marking yet another milestone in the global acceptability of Afrobeats.

But the man basking in the klieg light himself sees it merely as a stepping stone.

“I don’t think I’ve gotten to that point yet in my life, where I feel like I’m a superstar,” the 27-year-old tells Al Jazeera at his home, a townhouse in the upscale Lagos district of Lekki in July. “I feel like there’s still so much work ahead of me. I haven’t even dropped an album yet.”

Lojay is seated at the dining table as he answers, twiddling an empty ashtray and backing the staircase leading to the in-house studio and bedrooms. To his right, in the sitting room, two associates are watching on as the singer’s cousin and road manager plays the video game, God of War, on a massive TV.

“It made me feel good watching it, just knowing that I made music that could reach everybody,” he added. “There is a sense of verification, not validation that comes with that but I don't think I’ve gotten to that point yet and I hope not to get to that point anytime soon.”

“Maybe when Elon Musk starts listening to my music and he is like, 'Hi yeah, come to the Giga Factory, let's see what we can work on,' yeah. Maybe I might get like a little bit excited about that.”

Recently, the singer Rema, whose, Calm Down, song peaked at the number-three spot on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in July, toured India. That caught Lojay’s attention.

“What Rema did in India? That’s an award right there,” he said. And he is keen to replicate that elsewhere in Asia.

“Doing a stadium show in Japan, that's the icing on the cake,” he said. “Japan is one of those places that hasn't grown into Afrobeats as quickly as the rest of the world. It's one of those places that's far off east. A lot of them spend large periods of their lives without even seeing black people, let alone idolising black people and paying money to come and watch them in a stadium. That's an example of opening the sound to a new set of people and them just loving what you’re doing."