Vietnam's whale worshippers

Within shoreline communities, whales are gods of the southern sea.

The story goes like this: When Nguyen Van Loc left his grey concrete home on Ly Son Island and strolled towards his glazed blue boat, he anticipated a routine fishing trip - sunrise melting over the horizon, a rice wine breakfast, a slow search for shoals and, if they were lucky, a decent catch.

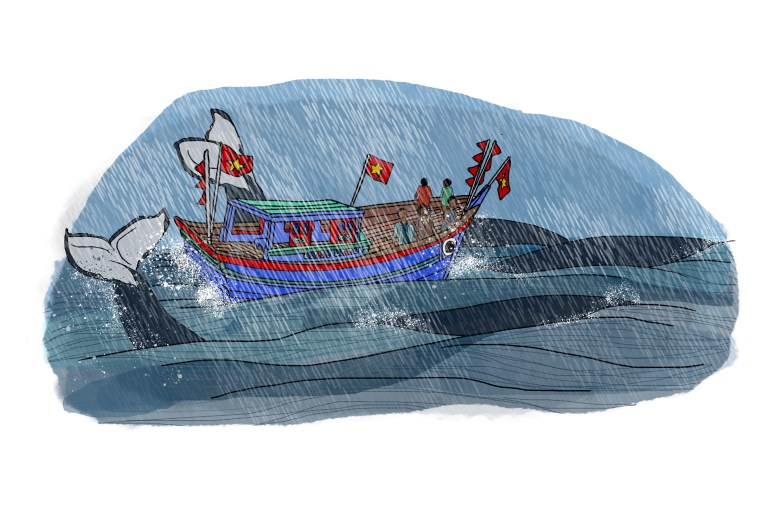

Yet within a few hours of venturing beyond the island’s offshore reefs, a storm threatened to capsize his plans.

Beneath galvanised skies, fierce winds hastened over the ocean, whipping sea spray into ghouls that lashed against Loc’s boat. Around the vessel, waves churned into steeper and steeper peaks that sent the crew crashing against the deck. Lightning lit up the ocean, shining a torchlight on their fate.

Death, Loc felt, was surely close.

After binding themselves together with rope - so their corpses would be found as one - Loc and his fellow fishermen gripped the boat’s gunwale and prayed for help. As they peered at the heaving sea, remembering ancestors who had fallen before them, a smooth, oblong form appeared, and a wise, barnacled eye stared back at them - as if looking directly into their souls.

The men, however, felt no fear, for it was to the whale god Cá Ông that they had directed their prayers.

As the men cheered in elation, another two whales appeared beside their boat.

Over the next few hours, the three cetaceans steered the fishermen away from a deep-sea death and towards home, where their story would spread through fish markets and restaurants for decades to come.

Upon hearing Loc’s tale, one might be tempted to dismiss his experience as a mind-blowing one-off. A miracle. A rescue of biblical proportions. Yet what’s striking about his story is not its singularity, but how often similar anecdotes surface within Vietnam’s shoreline communities. From southern Phu Quoc Island right up to the coastal city of Da Nang, fishermen habitually beguile listeners with stories of cetacean altruism.

Is there a morsel of truth in their tales? One can only find out by rising at dawn to walk through fishermen’s markets and searching for dozens of whale temples dotted along the south-central Vietnamese coastline.

'Gods of the southern sea'

We begin in the nondescript town of Phan Thiet, four hours east of Ho Chi Minh City, where Vuong Dao, the caretaker of a whale museum, regales visitors with ocean lore - including Loc’s tale. The paunchy, middle-aged figure in a starched blue shirt speaks with an air of quotidian politeness one might expect from an office worker. Behind him, the vast, arching ribcage of Southeast Asia’s largest preserved whale skeleton dominates the room as he unpicks each knot of Loc’s tale and the wider whale worship culture.

“This is the skeleton of Cá Ông,” he says. “It is over 200 years old. The whale died and beached here, so the fishermen held a funeral and buried him. After three years, they exhumed the grave and brought the bones here to worship.”

Local fishermen protected the whale’s bones for hundreds of years before they were reconstructed and displayed in the museum in 2003. And while nobody knows exactly where whale worship originates from, a Vietnamese legend offers ties to the same time period this whale perished.

In the late 1700s, King Gia Long of the Nguyen Dynasty was attempting a sea crossing with a small army when a frightful squall lashed his boat. The crew began to lose hope, until a whale arose from the depths and used its back as a fulcrum to steer the vessel to safety. To thank the beast, the king conferred upon him the name “General of the Southern Sea”, which was eventually shortened to Cá Ông, which translates variously as “Lord Whale” or “Grandfather Fish”.

Today, tales of whale burials and cetacean altruism even seep into state-run media.

In one article, Nguyen Quoc Chinh of Ly Son Island says he was fishing with 20 others near the Paracel Islands when a storm threatened to sink his boat. Astoundingly, a whale emerged - like a giant black rock - and the fishermen lay on the whale’s back for days, eating seaweed and drinking each other’s urine to survive.

“Whales usually save people at sea,” Vuong adds casually. “That is why the seafarers of Vietnam worship the whales. They also call them the Gods of the Southern Sea.”

Whale temples brimming with bones

The whale that saved King Gia Long purportedly died following the rescue, its fleshy carcass drifting to shore in three parts. One section reached the Can Gio mangroves along Vietnam’s southern coastline, the other two beached in Phuoc Hai, a small fishing village, and Vung Tau, now a port city two hours southeast of Ho Chi Minh City.

In the centre of Vung Tau today, a complex of temples devoted solely to worshipping whales lies within a seagull-strewn enclosure.

As we approach, a frail, elderly gentleman, whose face seems drawn into a permanent smile, hauls open a creaking metal door. Inside, the monk gestures proudly towards a glass case behind the altar, where the skulls and bones of more than 100 whales and other cetaceans lie in clusters under garish neon lights.

The quiet old man, still smiling in perpetual cheerfulness, sits on a stool behind the altar and rings a small gong as we gaze at the skeletons.

In Phuoc Hai, an hour up the coast from Vung Tau, a concrete promenade stretches before a strip of yellow-white sand scattered with fishing boats, old nets, plastic detritus, coconut shells, and the occasional dead fish. In places, whale art adorns the sea wall, around which retired fishermen sit in small groups spinning yarns or watching the sea.

One of the men invites us to join him at Phuoc Hai’s whale temple. The structure is more elaborate than the one in Vung Tau and the caretaker is at least half a century younger and wearing decorative robes. Within the temple, incense smoke drifts around dimly-lit rooms, ferrying pleas for prosperity up to the heavenly precincts.

Nguyen Ngoc The, the temple caretaker, recalls one sea voyage when a few fishermen tumbled overboard and drifted at sea for days. They couldn’t remember how they were saved but knew a whale must have fed them.

After washing up on shore, the men vomited anchovies and, after a brief discussion, concluded this must have been the work of Cá Ông.

“While working at sea, I saw how Cá Ông’s spiritual influence protects the fishing community,” The says. “Whenever fishermen go to sea, we must first of all pray … We cannot foresee treacherous waves, vicious winds, storms, or anything else that causes problems at sea. So, we pray to Cá Ông, and ask him to protect us and guide us to fish and shrimps in order to earn a living for our family.”

Certain aspects of Vietnamese culture also directly influence the rituals of whale worship.

For many in Vietnam, honouring the dead is arguably of greater importance than honouring the living. Traditionally, families organise ceremonies for death anniversaries and place even greater significance on them than birthdays

“If a whale dies at sea, whoever finds him must bring him ashore. That person is responsible for worshipping him and burying him respectfully. That person will mourn Cá Ông and must worship him on the 49th and 100th day after the whale’s passing, and on the one-year and three-year death anniversaries - as he does for his own grandparents,” The says.

“There were also many whales that drifted ashore yet were still alive. We came to the shore and prayed for them to return to sea and continue saving humans,” he exclaims. “But the whales could not do so because, on certain occasions, they came here to die.

“When a whale is departing this world, we let it be. We play drums and gongs to help his soul leave peacefully.”

Grave of the cetaceans

Beyond the temple grounds, down a sandy pathway, an altar lies in the centre of the whale graveyard - a strange, profound place whipped wild by sea winds. A few dozen graves rise in little hillocks in the sand with headstones displaying the name of the fisherman that found the whale, the boat’s registration number, and the date of death.

Locals visit the graves as we pass, lighting incense and laying down flowers and fruits. Two caretakers, fishermen Hai and Tu, linger near one particular grave.

One morning, Hai says he saw a whale drifting dangerously towards the shallows. He swiftly leapt into the water and hauled the creature back out to sea, before praying for its life on the beach. Fearing that the distressed whale would return once again, he spent the rest of the day keeping watch. By evening, after heaving the whale out to sea three times, Hai gave in. The men carried the whale’s body to the temple to worship, performed a burial ritual in the graveyard, and began mourning.

“If he was still alive,” Tu sighs, “we would have let him go back out to sea.”

Cetaceans of all shapes are buried here - and even one tortoise - yet the fishermen use only one phrase to describe them: Cá Ông.

From the graves, one can see the cerulean sea dotted with bobbing coracles and a concrete enclave where fishing boats huddle together in the harbour. Painted whale’s eyes adorn the bows of many boats here, with the symbolic gaze of this sacred animal said to offer protection to fishermen.

These animistic elements hint at whale worship’s likely origins in Cham culture - the people who lived across vast swaths of central and southern Vietnam from about the 4th century. On the outskirts of Phan Rang in central Vietnam, amid crimson soil and austere mountains, Cham expert Inra Jaka says Cham people respected elephants as the Ông of the jungle in the same way they regarded whales as masters of the ocean.

“Across the coast of Vietnam, they still have the blood of Cham people,” he says. “We respect the spirits. The master of the sea? We have to respect that.”

A show of respect

On Vietnam’s central coastline an hour south of Hoi An, coastal Tam Hai is a cut-off island in a typhoon-laden sea. Yet each spring, the local people here - and in numerous other locations along the coast - arrange the greatest show of respect conceivable for their seafaring guardian spirit: a festival to honour Cá Ông.

In the darkness before dawn on a gloomy March morning last year, loudspeakers that once warned of bombing raids broadcast the upcoming day’s weather: overcast with a chance of rain. A crowd of villagers, all dressed in their finest attire, congregate around a beach-adjacent temple as soft rain drizzles over proceedings.

Inside, a worshipper wearing a black ceremonial áo dài bangs a gong as a quartet of silver-haired musicians plays, one using his foot to tease out stirring notes from a traditional string instrument. Before the altar, village elders bow and pray to whale spirits in a temple erected for fishermen who died at sea, but were never found. One elder says Cá Ông returns the souls of fishermen lost at sea. Otherwise, their souls would roam the ocean as ghosts.

The villagers then dash down to the shoreline for the day’s greatest spectacle, their arms overloaded with flag poles and drums. In coracles, fishermen ferry worshippers and instruments alike to awaiting boats. Elderly gentlemen in crimson-and-gold áo dài clamber onto a temple boat decked out with brightly coloured bunting and an altar as a fleet of fishermen rev their engines in the shallows.

Moving as if inspired by motorbikes in Vietnam’s major cities, the boats race through the waves behind the temple boat. As the elder worshippers cast paper offerings for Cá Ông into the ocean and pray at the altar, pursuing fishermen proudly wave their flags and drink rice wine and beer.

Once back on shore nearly an hour later, the men laboriously carry the coracles on their backs the way turtles struggle under their shells, before strolling across the beach to another place of worship. Narrow sandy pathways lead to an opening where the graves of at least 50 cetaceans appear in rows before the steps of a 600-year-old temple.

Worshippers line up to pray at altars where flowers, meat, fruit and rice wine rest above paintings of cetaceans. In a funeral oration, the village elders list the whales who were disinterred over the course of the preceding year.

Bach Ngoc Lan, a 57-year-old retired fisherman, says they choose the 16th and 17th day of the second lunar month for the festival each year, with the dates serving as the collective anniversary of their ancestors' death and the start of the new fishing year.

“The entire village holds the biggest whale festival,” Lan says. “We wish for prosperity for the whole country and for the villagers here.”

Some locals said the ever-changing COVID-19 regulations meant few young people could come home to attend the festival and join in the games, and also cited rules for elders:

“Only those who are older than 60 - and still have a wife - can perform as elder leaders of the whale worship ceremony,” Lan says. “Middle-age people must watch and learn so they can perform after the elders pass away.”

The day’s rituals end after a final worshipping session in the centre of the island, before endless drunken karaoke - a perhaps unintentional but effective rendition of whale song.

An anthropocentric ritual

As the decorously dressed locals pray for the whales, smoke billows from a pile of burning rubbish on the shoreline - like a grotesque echo of a whale spurting water from its blowhole. Beyond the flames, plastic detritus and torn-up nets litter the beach.

According to a 2017 report by Ocean Conservancy, five countries - Vietnam, China, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand - dump more plastic into the ocean than the rest of the world combined. In November 2018, an autopsy on a dead whale that washed up in Indonesia found 1,000 pieces of plastic in its stomach, including 115 plastic cups, flip flops and plastic bottles. Four months later, a young whale beached in the Philippines. This one died from “gastric shock” after ingesting 40kg (88 pounds) of plastic bags.

An even bigger threat to cetaceans comes from bycatch, which refers to when they are caught unintentionally by those fishing for other species. More than 300,000 are killed every year in this way.

Global whale populations have long been in decline. A survey from 1999 found few cetaceans in the Vietnamese waters of the South China Sea. Surveyors found only bottlenose, spinner and humpback dolphins, and a finless porpoise - but no whales.

According to the researchers, possible reasons for this include “historically sparse populations due to natural ecological conditions in the Gulf or population declines caused by anthropogenic impacts, including accidental entanglement in gillnets, reduced prey availability from overfishing, and mortality caused by fishing with explosives.”

Whale worship has arguably also found itself caught up in geopolitics. On Ly Son Island off the coast of central Vietnam, local fishermen are pawns in territorial standoffs in the South China Sea, with Chinese ships repeatedly attacking and detaining Vietnamese fishing vessels from the island.

Duong Duoc, a 65-year-old retired fisherman, says he was held hostage after going fishing near the disputed Paracel Islands 15 years ago. After his damaged ship began to sink, forcing his crew to paddle in small coracles to a nearby island, a Chinese coastguard vessel found the men, who were promptly detained for six weeks on China’s Hainan Island. Upon returning to Ly Son, Duong immediately paid his respects to Cá Ông, whom he credits for their eventual safe return.

In her essay, Geographies of Connection and Disconnection: Narratives of Seafaring in Lý Sơn, Edyta Roszko says the island is “at the centre of a re-imagined map of the nation’s territory” and that local fishermen “tie their identity to the state emergency in connection with the Paracels and with Lý Sơn Island’s geopolitical role in this international dispute”.

In any case, whether resisting storms or a hostile foreign navy, the worshippers appease their whale god to seek protection.

An instinct to protect

Most followers of this faith say they have never personally seen or experienced a whale rescue. Yet tales of cetacean rescues are not limited to Vietnam alone. In his book, The Wild Places, Robert McFarlane shares the story of a father and son who were sailing in the Gulf of Mexico in 2004 when their yacht was capsized by a gust of wind:

“After night fell, the water became rich with phosphorescence, and the air was filled with a high discordant music, made of many different notes: the siren song of dolphins. The drifting pair also saw that they were at the centre of two rough circles of phosphorescence, one turning within the other. The inner circle of light, they realised, was a ring of dolphins, swimming around the upturned boat, and the outer circle was a ring of sharks, swimming around the dolphins. The dolphins were protecting the father and his son, keeping the sharks from them.”

The internet is awash with tales of dolphins protecting humans, while a humpback whale reportedly saved marine biologist Nan Hausen in the Cook Islands in 2018 by lifting her onto its head and sheltering her under its pectoral fin. Meanwhile, another humpback slapped its tail against the ocean’s surface to ward off a 15-foot (4.5m) tiger shark lurking mere metres away.

Marine biologist Robert Pitman, who spent decades analysing interactions between humpbacks and killer whales, says the humpback's protective impulses - for humans and sea creatures alike - likely draw from an instinct to protect its own calves from predators.

'Everyone believes'

Despite the prevalence of such anecdotes both within Vietnam and across the globe, the future of Vietnam’s extraordinary whale worship culture remains uncertain as young people seek office jobs in cities and avoid jobs in fishing communities or rice paddies.

At the festival in Tam Hai, 38-year-old fisherman Mai The Luc recounts a Vietnamese proverb: “People say: ‘When the bamboo gets old, fresh bamboo sprouts grow’, which means that when this generation dies, children will take their place and maintain the custom, so we will not lose it.”

A few hours later, after leaving the festival, we wait for a boat back to the mainland in a café overlooking the sea. Noodles and other waste from the shop smear the shoreline rocks. On the surface, flecks of white polystyrene bob like tiny icebergs that never melt. Shimmering oil clings to the surface like huge iridescent jellyfish.

When asked if he is interested in the festival or the culture of worshipping whales, the young teenager working in the café looks up only briefly from his smartphone to say: “I’ve got to work.”

This seismic generational change defines modern-day Vietnam. Grandparents who carried out backbreaking work during years of communist revolution cannot relate to grandchildren desperate to escape claustrophobic family ties, move away from home and share their lives on Instagram.

Yet the whale worshippers take little notice. In Phuoc Hai, when asked if she thinks the belief in Cá Ông will fade away one day, a fisherman’s wife on the sea wall refuses to even entertain the idea.

“It will not. It will always be the same. When I was young, I didn’t know anything, but now I am older, I believe,” she says, before adding simply: “Everyone believes in Cá Ông.”